Ian Regan • Apr 16, 2019

Voyager Wide-Angle Views of Jupiter

Last month marked the 40th anniversary of the historic Voyager 1 encounter with Jupiter in 1979. Voyager 1 was not the first robotic visitor to Jupiter; Pioneers 10 and 11 flew past the gas giant in 1973 and 1974. But while the Pioneers’ primitive spin-scan photopolarimeters took very good, groundbreaking images of the planet, they couldn’t compete with the TV cameras of the Voyagers.

The cameras, while not at the forefront of technology in the late-1970s, were still a reliable and proven method of capturing images in deep space. They had a pedigree stretching back to the early Mariner probes—not surprising, given that the Voyager program was essentially a continuation of Mariner (the two Voyager probes were developed under the moniker ‘Mariner-Jupiter-Saturn’).

Each Voyager carried a pair of TV cameras, mounted behind telescopes of differing focal length, giving the operators the option of taking images spanning 0.4 degrees (the NAC or narrow-angle camera), or 3 degrees (the WAC or wide-angle camera). In traditional photographic terms, both systems are squarely in the telephoto category.

Most of the valuable photographic data came from the NAC, given the greater resolution it offered. However, the overlooked WAC had two principal roles: to provide context views of the highly localized NAC shots, while also providing continuous photographic surveillance of global-scale features on Jupiter and its moons near the period around closest approach.

Voyager 1

Jupiter is huge. On 17 February 1979, Voyager 1 was no longer able to fit the planet into a single frame of the narrow-angle camera, even though the spacecraft was still a staggering 11 million miles away.

The wide-angle camera was similarly overwhelmed on 3 March 1979, when the planet was 1.4 million miles distant.

All Voyager images of Jupiter captured on approach were usually taken with the NAC, and show a near fully illuminated globe, with the morning terminator visible just shy of the planet’s unlit, western limb. As Voyager 1 grew closer to the planet, its trajectory gave its cameras a view of a fully illuminated Jupiter. On 2 March, the phase angle dwindled to as little as 0.2 degrees, analogous to a typical full Moon as seen from Earth.

From that point onward, with closest approach just a few days away, Jupiter presented a markedly different face to the spacecraft—one where the night terminator now became visible on the eastern extent of the gaseous sphere.

I wondered if it would be possible to reconstruct this seldom seen face of Jupiter: a global portrait with the night terminator hugging the eastern limb. At this distance, narrow-angle imagery was all but useless for this purpose and data gathered by the lesser-celebrated wide-angle camera offered the only possibility.

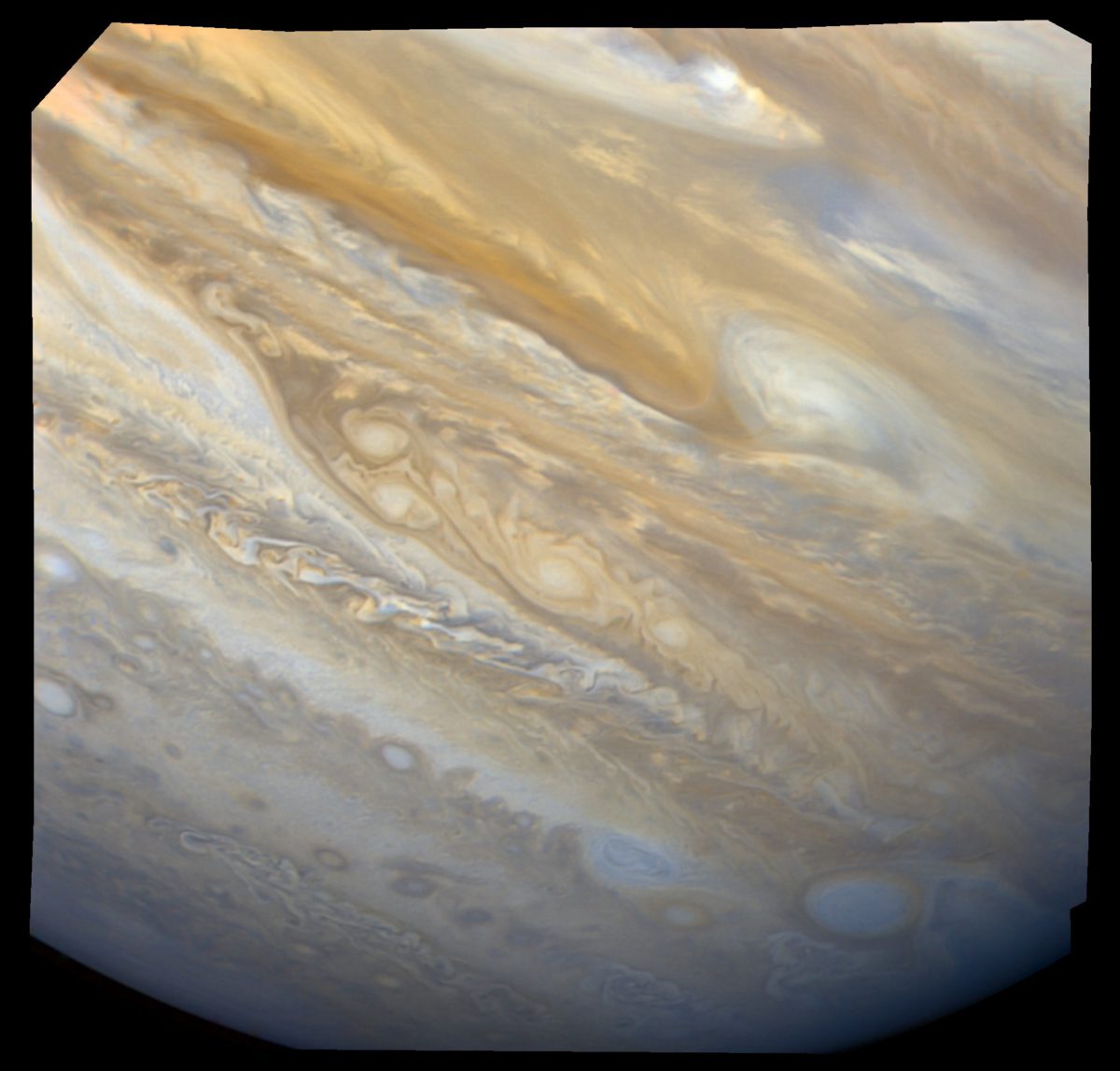

For Voyager 1, the wide-angle images captured over a 24-hour period prior to closest approach were not sufficient, both in spatial and spectral coverage, to compile a representative color mosaic of the planet. A great quantity of frames were trained (understandably) upon the Great Red Spot, leaving rather meager coverage of everything else.

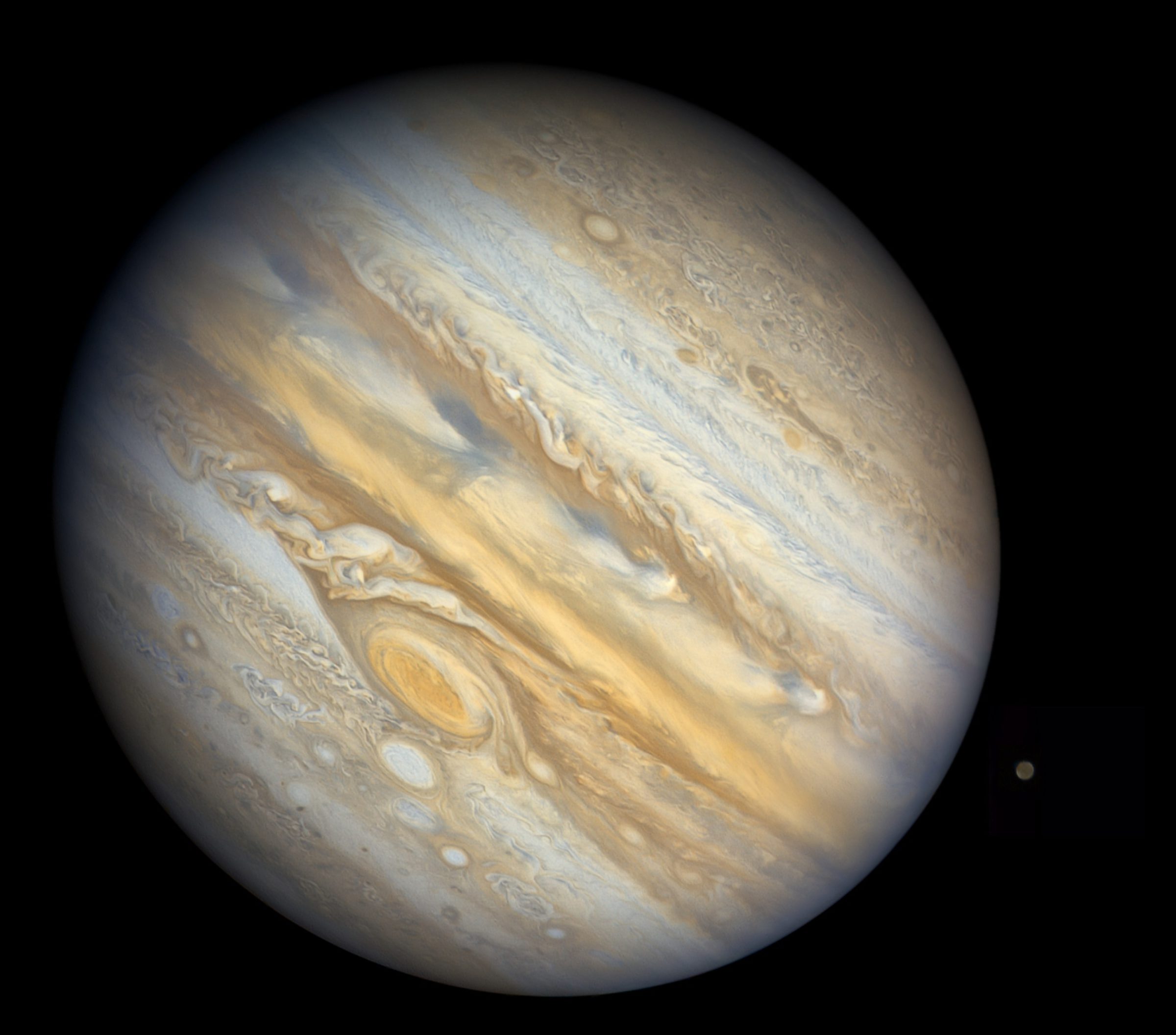

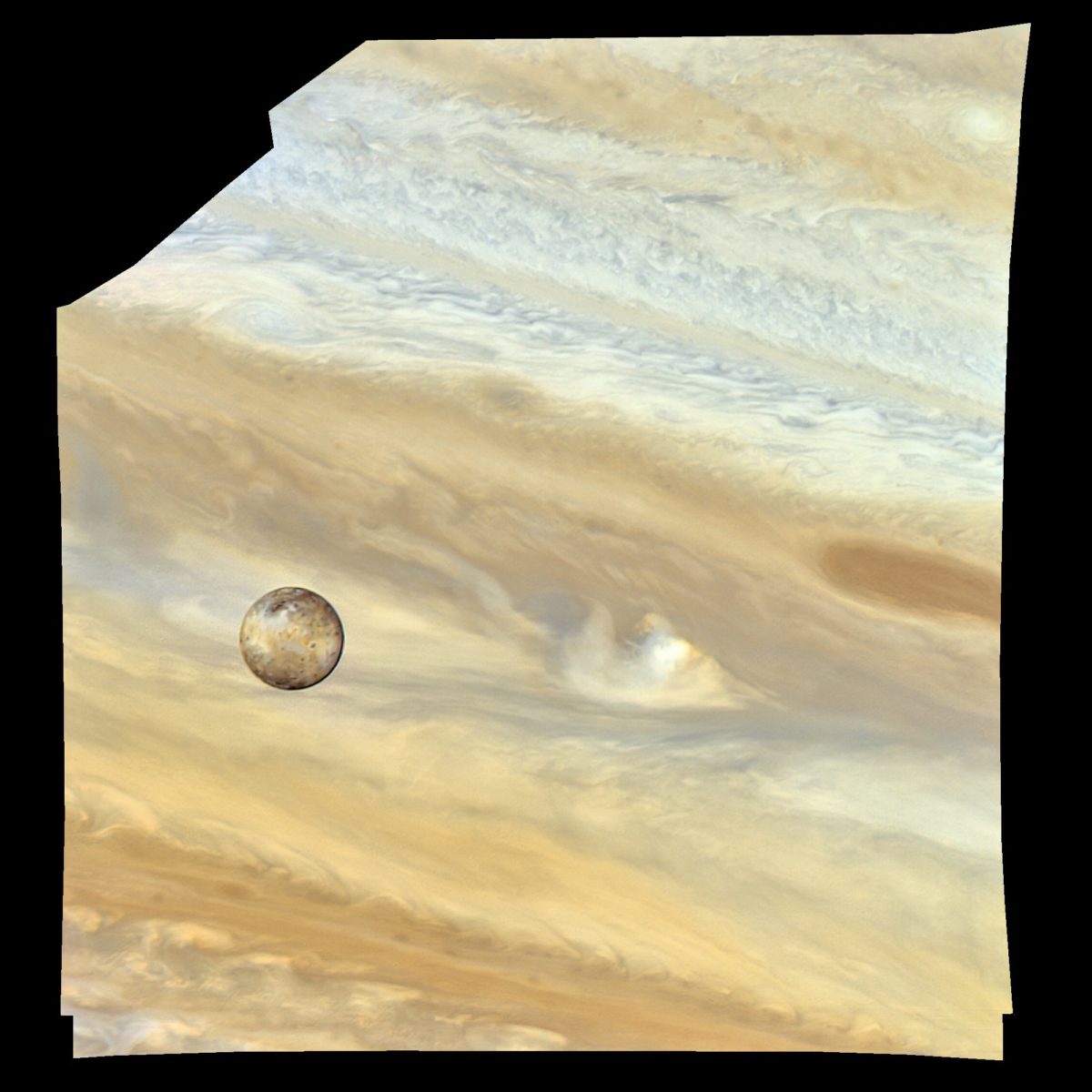

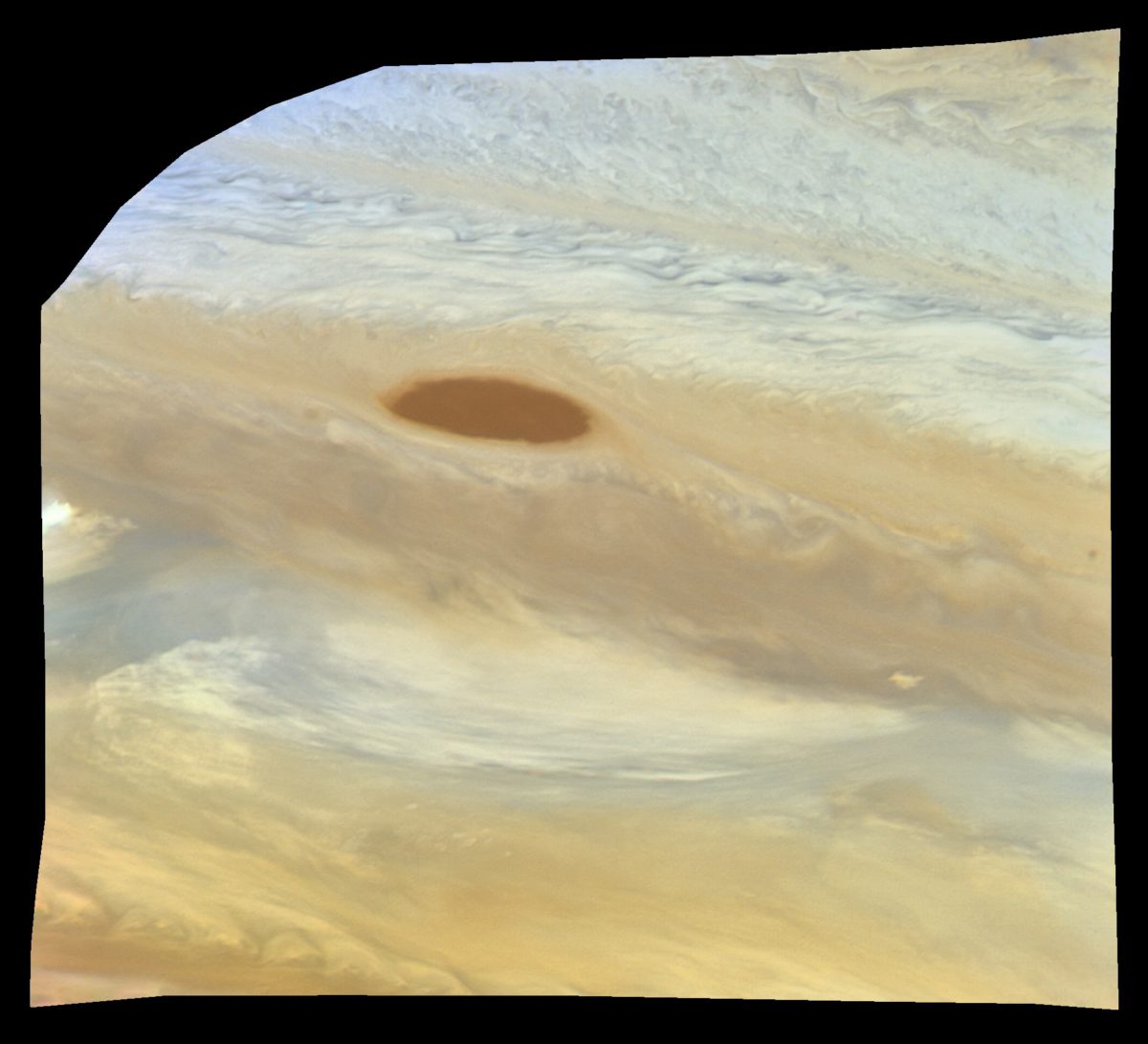

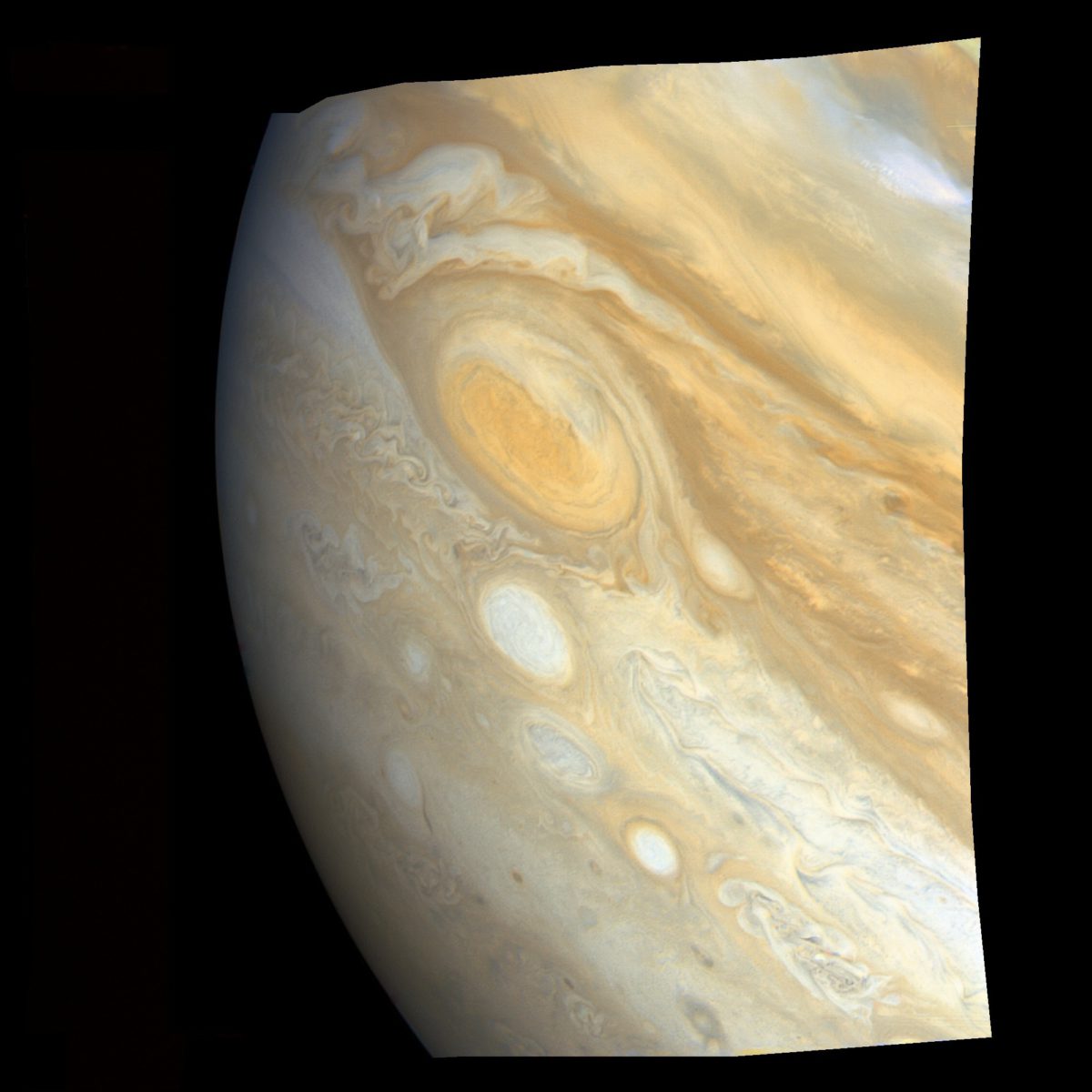

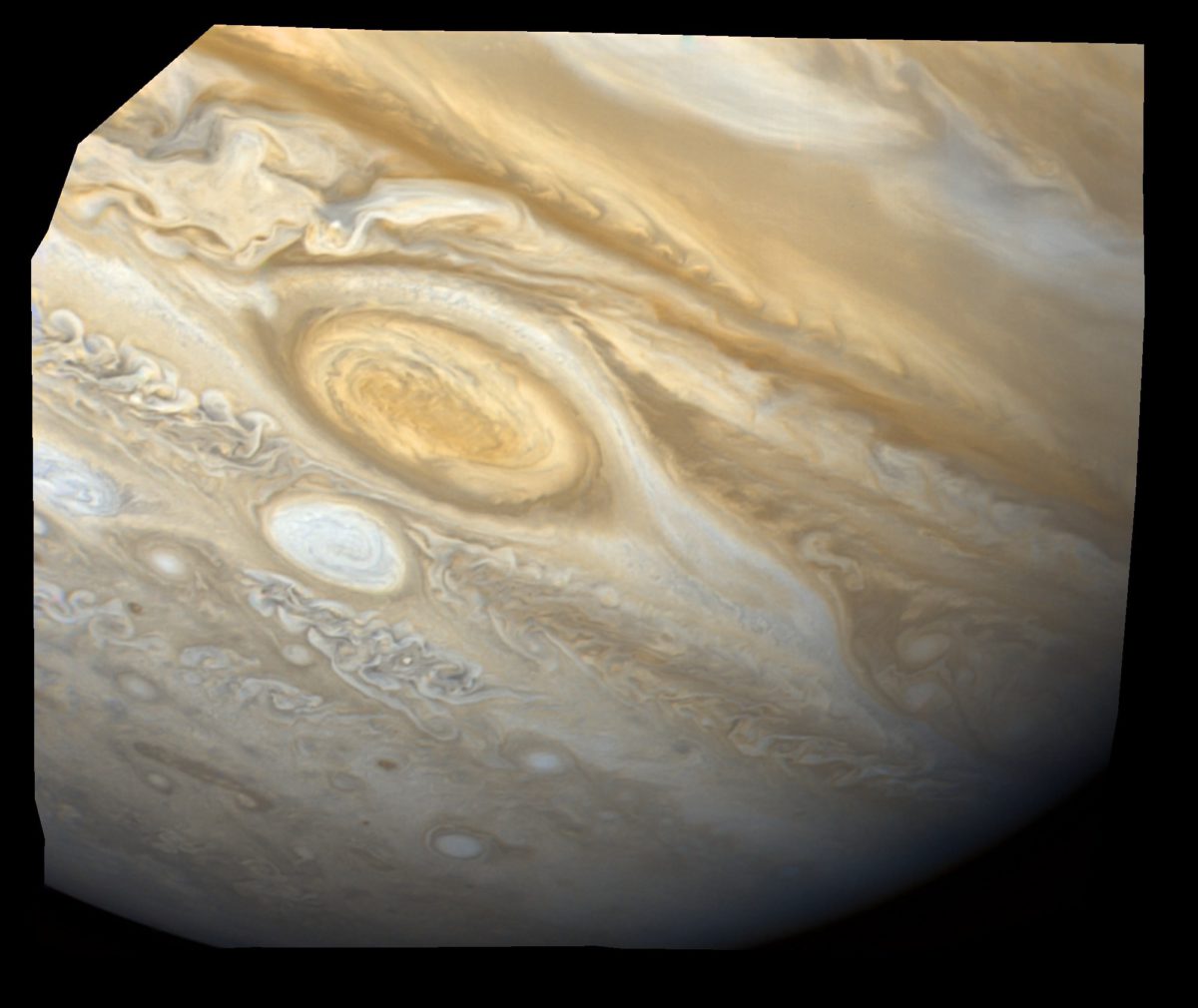

However, I found it possible to combine data collected through the orange, green, blue, and occasionally violet, filters to produce the following mosaic of Jupiter’s western limb, as seen by Voyager on the evening of March 4th, 1979:

Io can be seen transiting the planet, as the Great Red Spot comes into view. Given that the three principle WAC color composites used were captured at 17:11, 21:21, and 21:37 (all times UTC), the view is somewhat of a Frankenstein creation, as Jupiter’s rapid rotation ensures that atmospheric features seen here at different latitudes are not shown in proper relation to one another. Despite this drawback, this mosaic gives a very effective if somewhat illusory impression of the face that Jupiter presented to Voyager 1, just 14 hours before closest approach.

Voyager 2

Sixteen months later, the second Voyager (wielding a TV camera with marginally greater sensitivity), focused on the Jovian system.

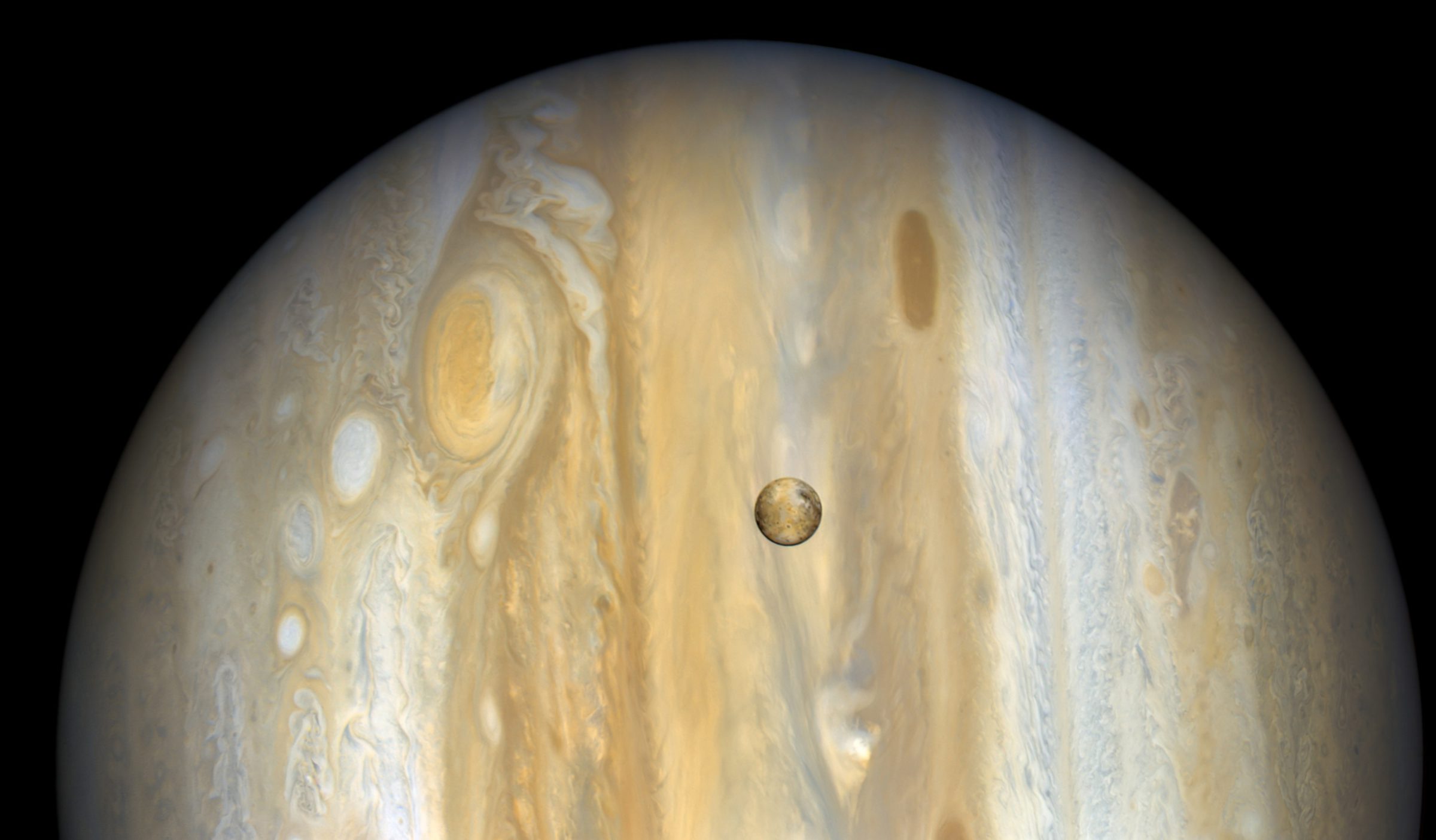

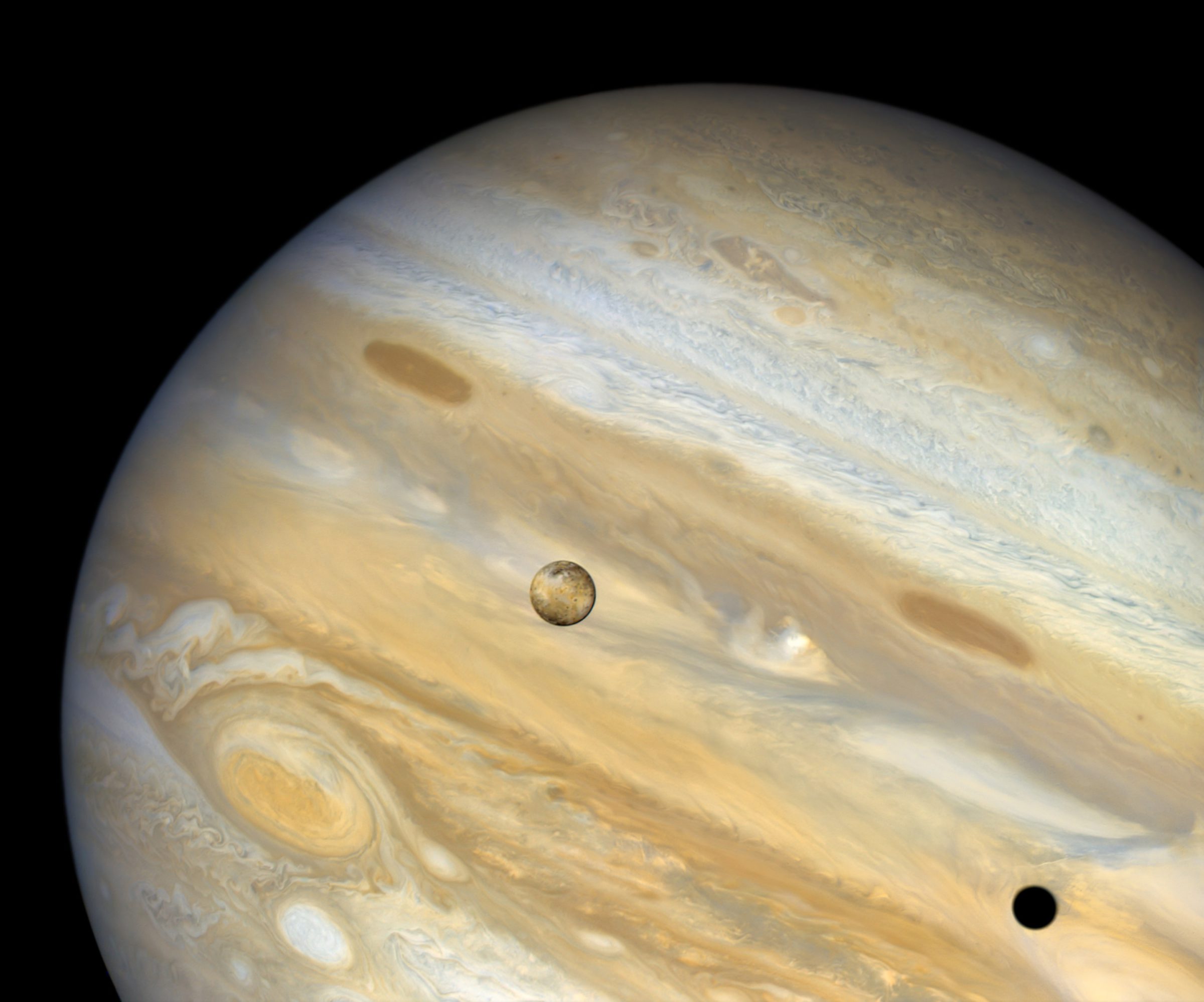

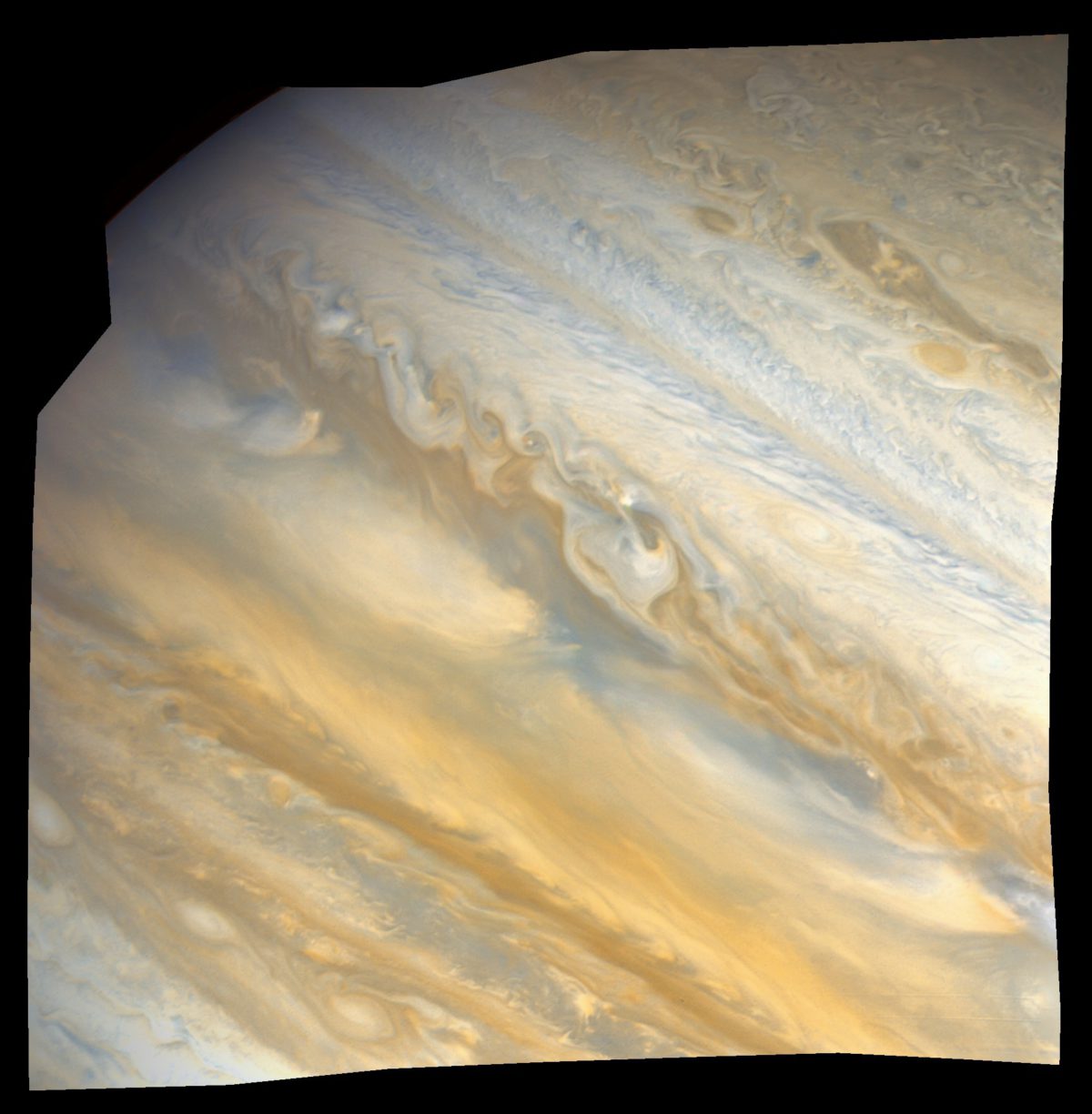

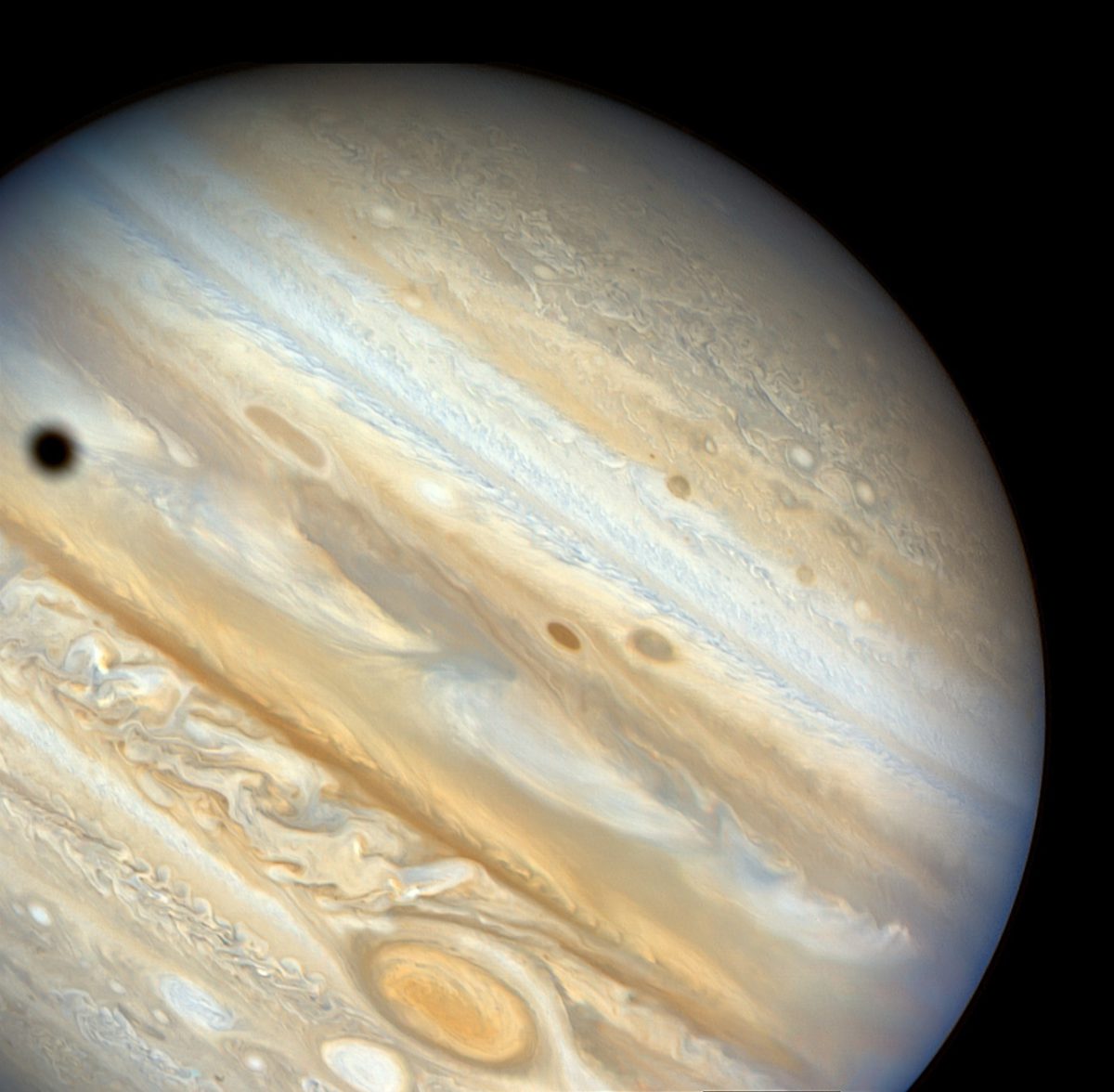

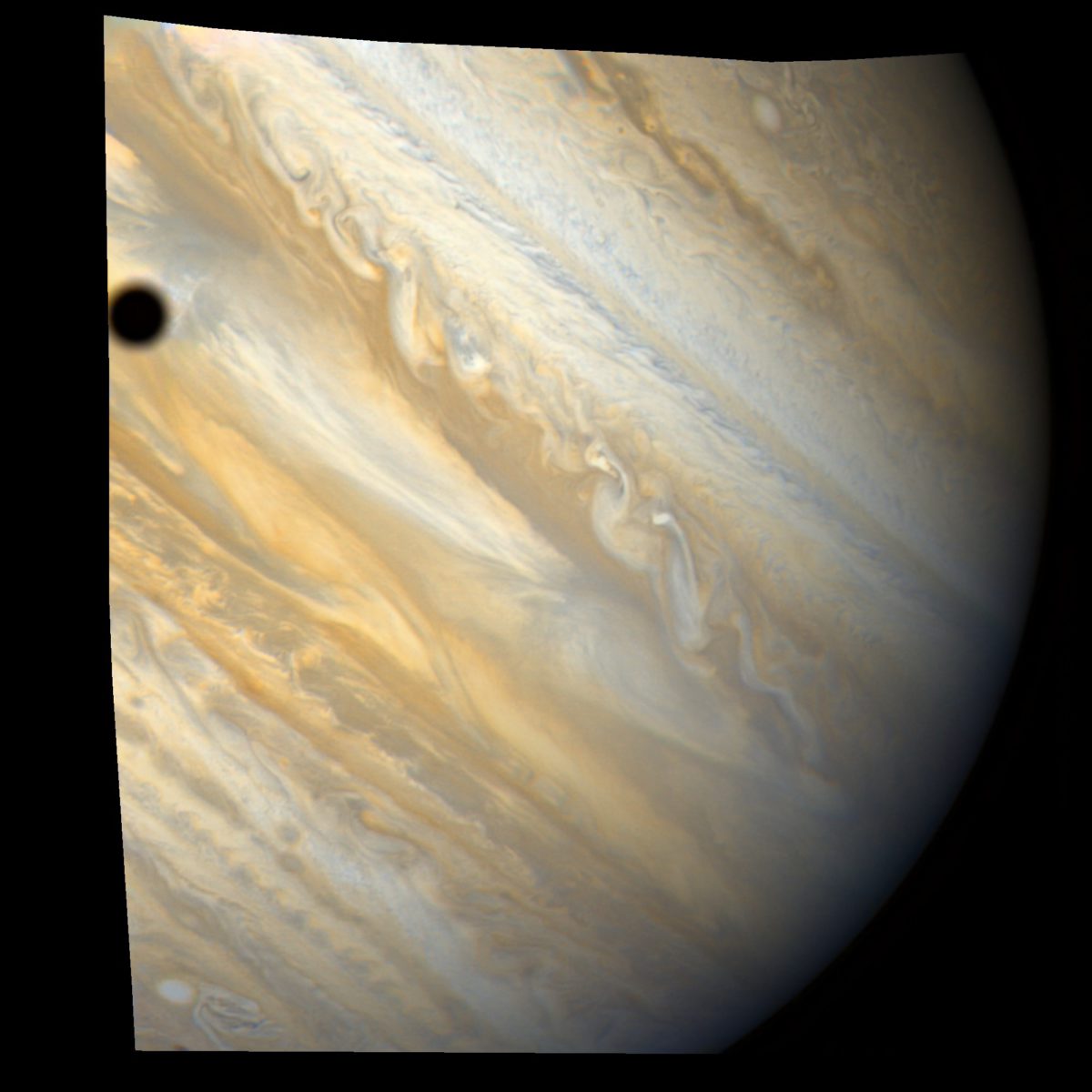

In the evening of 8 July 1979, a mere 25 hours before closest approach, Voyager 2’s WAC captured a more comprehensive assortment of images of Jupiter than its twin, allowing a full globe portrait of the planet to be composed, from six 3-filter color composites (either OGB or OGV).

Again, these observations spanned a non-trivial time period (from 18:32 to 22:35 UTC), so the relative longitudinal positions of various cloud features cannot be trusted.

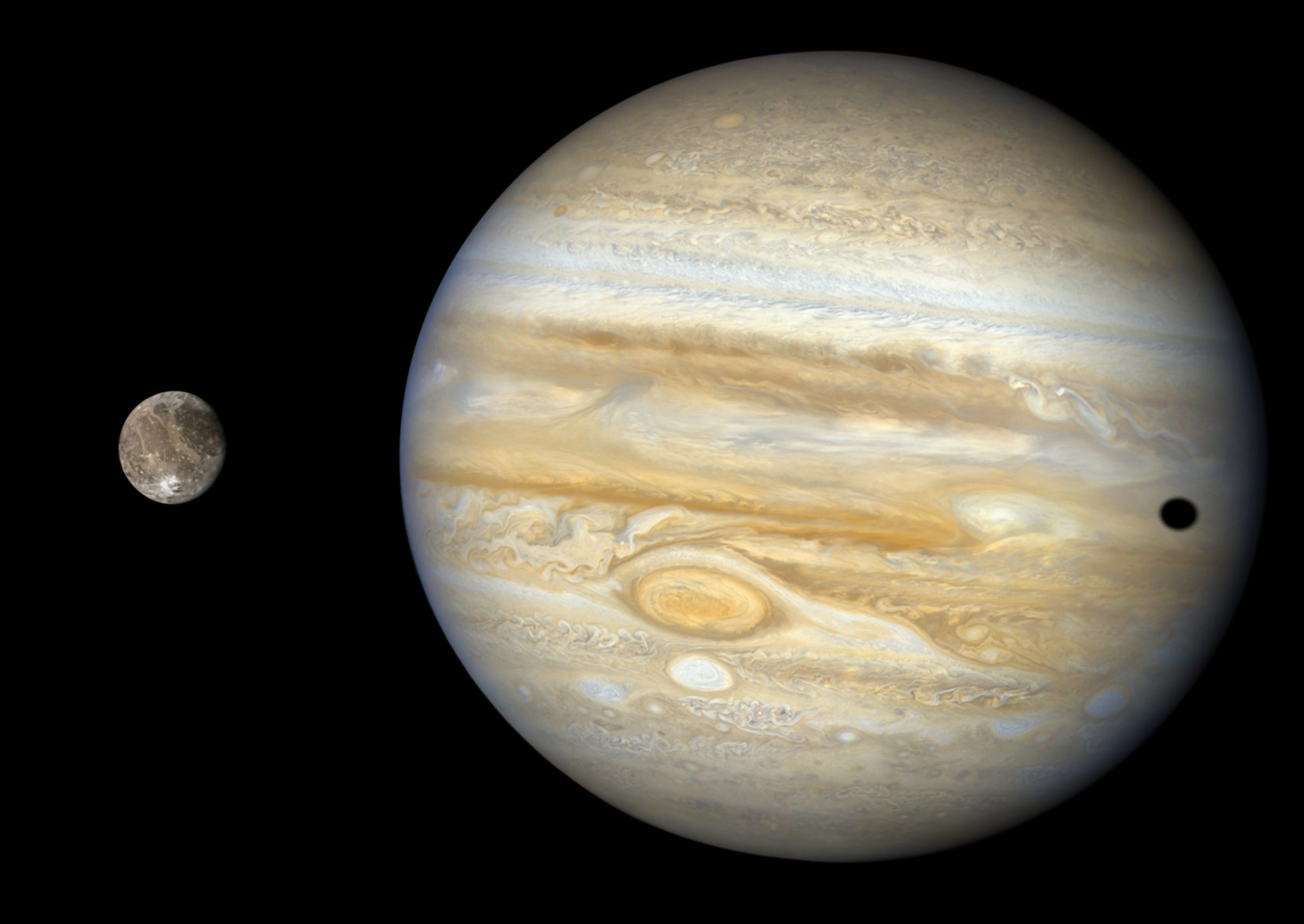

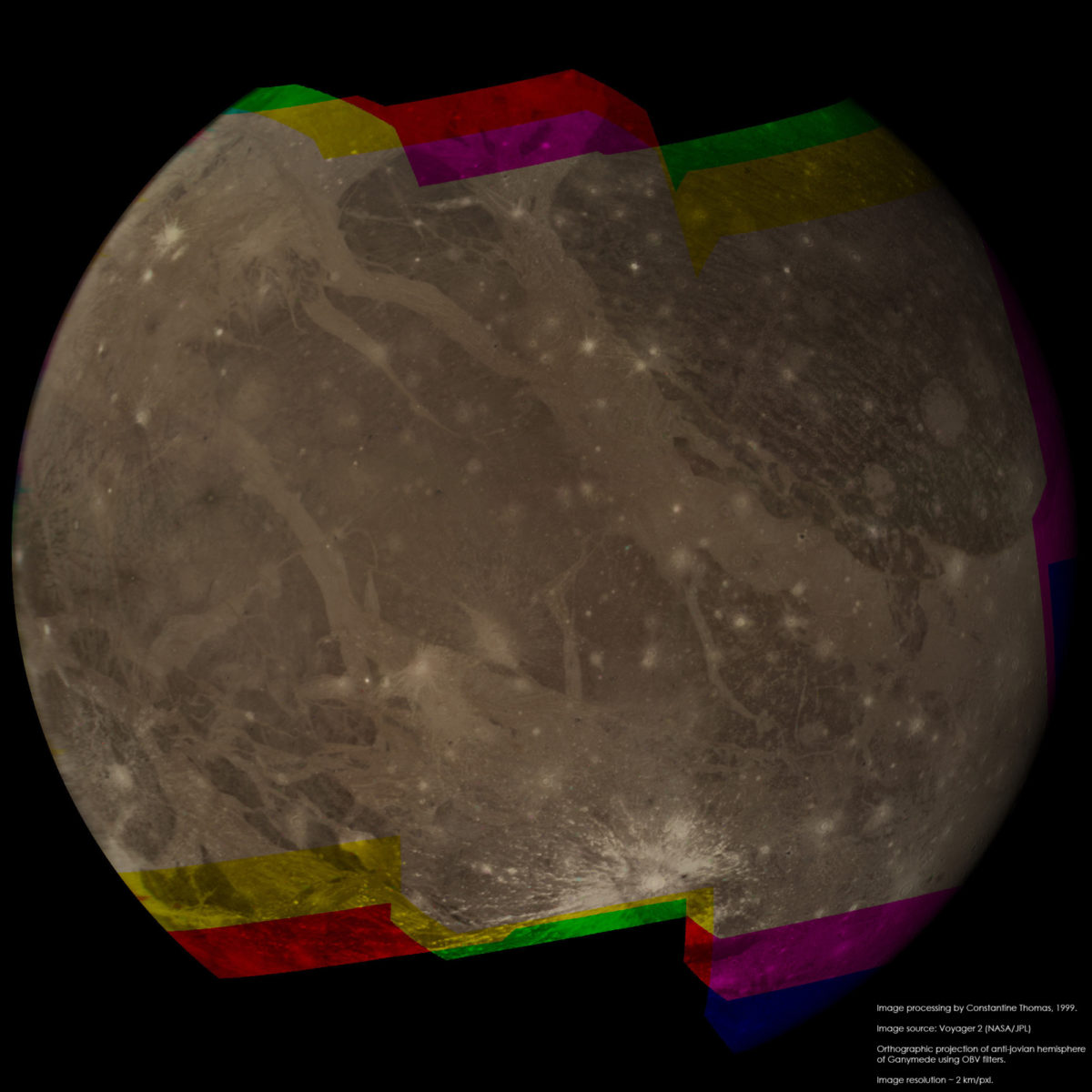

As an added bonus, the shadow of Ganymede was captured crossing the face of Jupiter; it is shown here as seen by the WAC at 20:04 hrs. In fact, after these images were taken, Voyager 2 turned its suite of instruments toward the moon itself, capturing many images through both camera systems. A wide-angle color composite of Ganymede, taken as context for the higher resolution mosaics, has been added to the Jupiter mosaic to complete this panoramic vista.

While later emissaries to Jupiter, most notably Cassini and New Horizons, captured views of Jupiter from this particular angle, these unique Voyager perspectives have been buried in archived data until now. Long live the Voyagers!

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth