Anatoly Zak • Sep 25, 2017

NASA, international partners consider solar sail for Deep Space Gateway

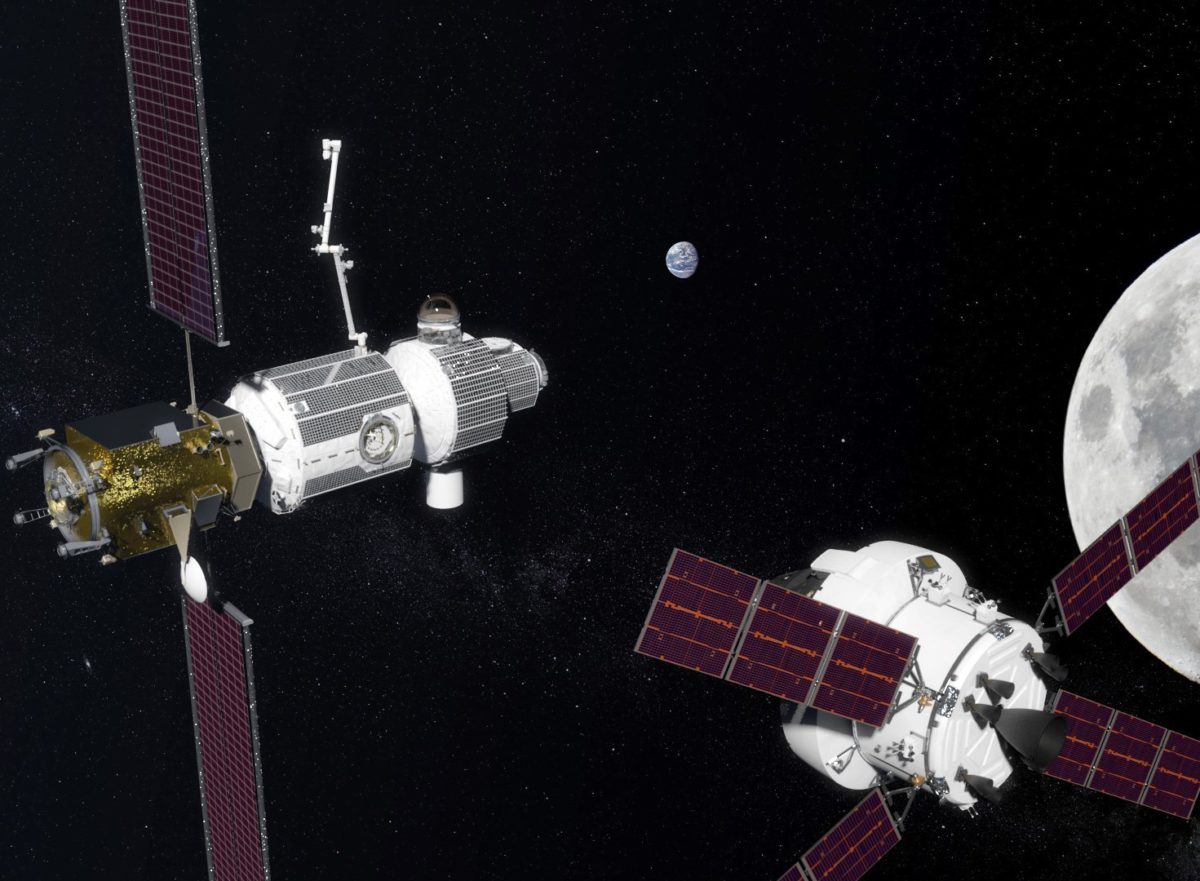

It sounds like it comes straight from an Arthur C. Clarke story, but an international team of engineers is considering equipping a future human outpost orbiting the Moon with a solar sail. Harnessing the slight pressure of solar radiation, a super-thin reflective film might help steer the Deep Space Gateway, or DSG, which is being designed by five space agencies to succeed the International Space Station.

The solar sail concept was presented last month by the Canadian Space Agency, or CSA, at the latest meeting of ISS partners. The event, specifically dedicated to DSG planning, was held at the European space center, ESTEC, in Noordwijk, Netherlands.

At this point, ISS partners are still debating whether to use the sail for practical purposes on the near-lunar station, or only as an add-on experiment to demonstrate its future potential, including possible use on a Mars-bound spacecraft. One of the declared goals of the DSG is to test technologies which could pave the way to the first human journey to the Red Planet.

It is likely the first time solar sailing technology has been considered for a spacecraft carrying humans. Only Japan's IKAROS, launched with aboard the Venus-bound Akatsuki spacecraft in 2010, has demonstrated controlled flight by light. The Planetary Society's LightSail 2 spacecraft, scheduled to launch next year, would be the second.

According to an internal document presented to the ISS Exploration Capabilities Study Team, Canadian specialists believe a solar sail could play a secondary role in orienting the DSG, saving fuel for traditional rocket thrusters designed to maintain the outpost's position. Under this proposal, the main thrust for the station's maneuvers still comes from electric propulsion and traditional liquid propellant engines.

The baseline concept used for initial calculations calls for a rectangular sail spanning an area of about 50 square meters, deployed on the exterior of the station by a robotic arm. This could reportedly save at least 9 kilograms of hydrazine per year needed to keep the outpost correctly oriented in space. Although a relatively small number, 9 kilograms per year adds up over the station's projected 15-year mission, especially when considering the tremendous cost of delivering cargo to lunar orbit. The station's current design allocates 135 kilograms of hydrazine fuel for counteracting gravitational disturbances, as well as solar radiation pressure exerted on the station's exterior in lunar orbit. At least part of this attitude-control job could be shifted to a solar sail.

When the solar sail is not needed, it could be either folded or hidden behind the station's solar panels relative to the Sun, so that solar radiation no longer presses on its surface.

Besides the rectangular panel, other shapes and designs are also on the table, including discs and umbrella-type structures. One clever concept proposed to attach a foldable sail to a robotic arm, which will bend around its elbow to unfurl the sail like an old-fashioned fan.

The final architecture of the solar sail is important because the design team is hard-pressed to keep the mass of the sail structure to an absolute minimum to justify its effectiveness. Very preliminary estimates show the mass of the solar sail system could be kept between 38 and 52 kilograms.

Potentially, the solar sail could also be used as an extra power-generating array, but the cost-benefit analysis of such a combination is also in the early stages. Engineers will also be challenged to pick the right compromise between the size and mass of the sail; the bigger the sail, the faster it can steer the station, but the larger it gets, the more weight penalties it brings to the whole project.

To keep the mass of the sail to a minimum, engineers considered Dupont's polyamide film, which measures just 7 to 25 micrometers thick.

Before its journey to the vicinity of the Moon, a prototype of the sail could be brought to the ISS to test its deployment mechanism and operations.

The Canadian Space Agency has yet to provide any public information on the solar sail concept for the near-lunar station, but in March, the agency announced Canada is "exploring how to contribute to the exciting new opportunities that will ensue as humanity takes its next steps into the solar system."

In another press release August 18, the CSA announced it had award a $2.75 million contract to the aerospace company MacDonald, Dettwiler and Associates, perhaps best known for the country's Canadarm systems. The official goal of the contract was to identify the requirements to build a deep-space exploration robotics system, which could be used to operate and maintain a future space station near the Moon. "This early-stage analysis will contribute to a better understanding of the technologies and equipment needed to support future international missions beyond the International Space Station," the announcement said.

According to a NASA source, the solar sailing concept will need further analysis, but is already being seen as promising and considered to be a good candidate at least as a demonstrator aboard the DSG, if not a fully operational system.

The construction of the Deep-Space Gateway is expected to begin in the first half of the 2020s with the help of NASA's SLS rocket and Orion spacecraft. The near-lunar outpost will be the main destination for the Orion during the next decade, promising to give NASA and its partner agencies enough experience for human missions beyond the Moon and, possibly, to Mars in the 2030s.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth