Marco Parigi • Feb 27, 2017

Citizen scientist spots changes on Rosetta's comet

Back in 2015, as Rosetta’s comet, 67P, was approaching perihelion, scientists noticed the surface changing before their eyes. These “very significant alterations,” according to the European Space Agency, were located in Imhotep, the smooth region on the comet’s large lobe.

One exciting aspect of the Rosetta mission was that on a comet, there was a high expectation that visible changes would occur during perihelion, which is the point in the orbit where the comet makes its closest approach to the Sun. How these changes relate to the processes theorised to happen on comets is still a work in progress. Many new papers are proposing various mechanisms, and data from the mission will be informing scientific results for years to come.

Thousands of Rosetta images are available from the European Space Agency. In March 2016, ESA put out a call for citizen scientists to help spot changes on the comet’s surface.

I like looking through comet images for changes, so I decided to contribute. It’s a wonderful way for non-scientists to get involved. The process has been very rewarding—as one becomes more and more familiar with features, changes start to jump out, and there are usually multiple images of the same area to help validate differences.

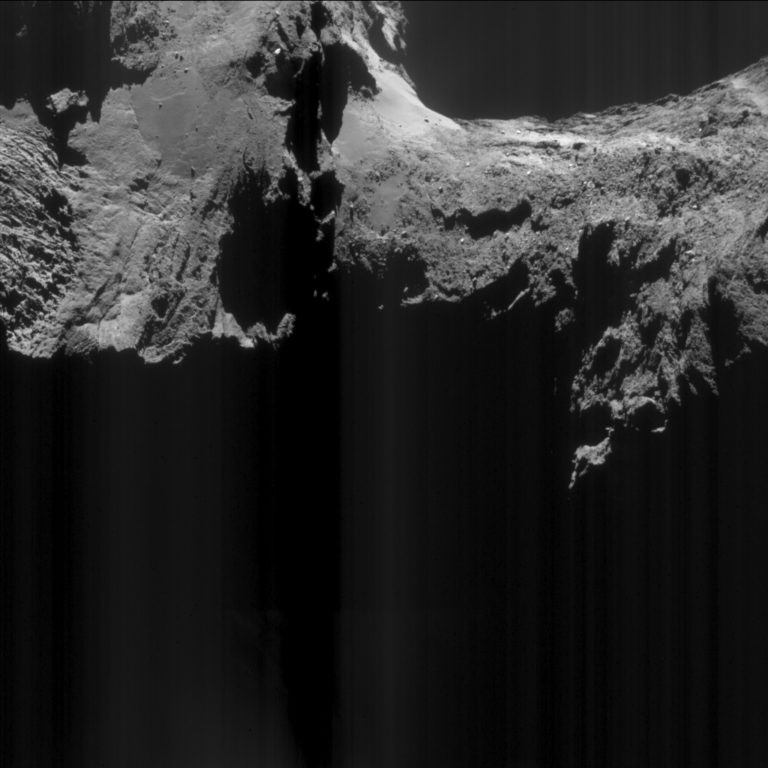

Here’s a change I discovered last year. Take a look at these two raw images. Can you spot the difference?

It’s tricky! The lighting and camera angles are slightly different. But if you look closely, you’ll notice this:

Do you see it now? Part of the cliff has apparently collapsed during the interval between the two images.

With the help of fellow comet enthusiast Andrew Cooper, I concluded the time window for the cliff collapse can likely be narrowed to between February 18 and March 1, 2016. That means it happened after perihelion, with comet 67P outside the orbit of Mars—which is interesting, considering the most dramatic outbursts of activity occurred closer to the August 2015 perihelion.

What’s also interesting about this discovery is where it happened. The “top” of the cliff is located in a region called Anuket, and the “bottom” is in a region called Sobek. The cliff collapsed from Anuket into Sobek.

I became very familiar with this part of the comet due to my work on narrowing down the time of the collapse. In the September 2016 issue of the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics, a paper was released describing the different regions of the comet. Reading the through the paper, I noticed a discrepancy: the border between Anuket and Sobek was wrong. Here’s what the paper showed; can you see the cliff from above, contained entirely within the Anuket region?

I described the mapping discrepancy in the comments section of ESA's original article asking for citizen scientist contributions. The paper’s lead author, Ramy El-Maarry, replied to say I was correct, and an erratum was issued correcting the boundaries.

Here is the upgraded diagram from the paper’s erratum, which was published in February 2017. Notice how the boundary between Anuket and Sobek now runs along the bottom of the region where the cliff collapsed:

The front page of the erratum paper acknowledges me and Andrew Cooper for having spotted the inconsistencies. Not bad for a couple citizen scientists! I believe it is a wonderful idea for ESA to make spacecraft data available to the public, and allow everyone to contribute to the mission.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth