William Blume • Jun 07, 2017

Remembering planetary scientist Michael A’Hearn

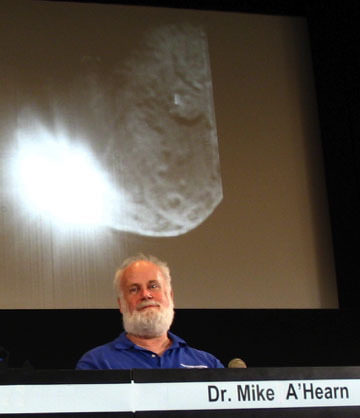

Planetary scientist Michael A’Hearn passed away on Monday May 29. As an engineer at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, I had the privilege to interact and learn from this important scientist over twelve years. I met Mike as he took over leadership of an unlikely proposal to NASA in 1998 that resulted in the close exploration of two comets by the Deep Impact spacecraft. A gentle bear of a man, often clad in shorts and a Hawaiian shirt, Mike was a renowned cometary scientist from the University of Maryland, but still green about the challenges of leading a complex engineering project development. The coming years of that project would give him many frustrations, more grey hairs in his thick beard, and finally two exciting and successful encounters at comets 9P/Tempel 1 and 103P/Hartley 2. He has a remarkable legacy in cometary science, but even more importantly in the careers of many younger scientists who flourished with his encouragement and mentorship.

My role on the Deep Impact project was to lead the mission design development. For those of us who worked on the mission—whose goal was to spear a comet and study the aftermath—Mike was a calm influence in the center of a turbulent project development. NASA had passed on our first proposal to the Discovery Program in 1996, despite the hard work of the science team, first brought together by PI Michael Belton, and many engineers at Ball Aerospace and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Mike A’Hearn was promoted to provide some younger blood as the principal investigator for the 1998 proposal, and refinements guided by now-Deputy PI Belton and instrument expert Alan Delamere strengthened the proposal. Our optimism peaked when the detailed proposal was accepted by NASA in 1999, but multiple crises soon followed as the budget grew, schedules stretched, and difficult compromises had to be made. Dismayed as he saw instrument and mission capabilities reduced and the project threatened with cancellation, Mike had to grow into the role of an assertive project leader to save the science that he had promised to NASA. In this period he continued his multiple scientific responsibilities with exhausting travel and frequent sessions at NASA headquarters to assure top managers that the project could still succeed.

During the proposal development, we had promised NASA to reach the target Tempel 1 on the Fourth of July 2005. The project ended up a year late in delivering the Deep Impact flyby spacecraft and its attached impactor to the Cape Canaveral launch pad in January 2005, but fortunately its target could still be reached on the planned date. As the operations teams crammed what had been planned as eighteen months of flight activities into six months of intense effort, Mike marshaled the science team and their collaborators in final preparations for an expansive campaign of observations of the comet and the impact event. This included studies from ground and other space observatories, including Spitzer and Hubble.

By the night of the encounter, I was only an observer in the science team’s operations center at JPL. I was also thinking about the possible extended mission we could pull off if the impact was successful and the flyby spacecraft survived its flight through the dusty coma of Tempel 1. Mike was off in the engineering control room to make any final decisions if any contingency plans had to be implemented. As the size of the comet began to grow in the images being returned, tension in both rooms grew. Would the self-guided impactor reach its target while traveling at a relative speed of 10.2 kilometers per second, and what would that explosion look like?

Despite that excitement, I was just as impressed by the interactions of the science team as they went about their roles as organized with Mike. There was a smooth harmony and little hierarchy in the work of the science team, which included several women as co-investigators and among the many young collaborators and graduate students assisting the team. The team cheered as the first images came back showing a dust cloud erupting from the comet nucleus, but within minutes there was only the hum of quiet collaboration between the scientists as they worked the first data sets.

After the successful Tempel 1 impact and data return, the Deep Impact spacecraft was routed to another close encounter with comet Hartley 2 in 2010. The scientific return from those investigations was only a small part of Mike’s legacy in planetary science, which included decades of leadership in important collaborations across the globe on studies using ground and space-based observatories. From studies of Halley to Shoemaker-Levy 9 to Churyumov-Gerasimenko with the Rosetta team, his work fills many volumes in the scientific literature. But more importantly, his teaching and mentorship of many early career scientists continues his work into the future.

Many colleagues in the planetary science community are remembering Mike’s influence on their careers and can better express the value of his contributions. I’ll conclude with thoughts from just a few of them:

Astronomer and co-investigator Karen Meech, who organized the Deep Impact ground observing campaign, was on top of Mauna Kea on the night of the encounter. She recalled his influence on her career: “Mike was instrumental in mentoring the careers of many planetary scientists. He was always very good at making sure junior people working with him were taught well, then given the chance to develop and eventually lead. In my career, he was both mentor, colleague and friend and I will always remember fondly his support, great scientific insight and his humor. He was a wonderful colleague to work with.”

Gretchen Walker, Vice-President for Learning at the Tech Museum of Innovation, remembered Mike encouraging her work on Deep Impact science plans while working on her Master’s degree in science education: “This reinforcing of my confidence—that just because I had chosen an educational path did not invalidate my ability to do science or to contribute to discovery—is one of the foundation stones that set me on my way in my current career.”

Professor of Physics and Astronomy Laura Woodney recalled his influence as her thesis advisor: “He made everyone who worked with him feel special. Your question was always the most important in the world when you asked it—not the dozens of other things he was working on simultaneously. He was generous with his keen scientific insight, his time and his support.”

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth