Paul Gilster • Mar 06, 2015

Seeing Ceres: Then and Now

This article originally appeared on Paul Gilster's blog, Centauri Dreams, and is reposted here with permission.

I’m interested in how we depict astronomical objects, a fascination dating back to a set of Mount Palomar photographs I bought at Adler Planetarium in Chicago when I was a boy. The prints were large and handsome, several of them finding a place on the walls of my room. I recall an image of Saturn that seemed glorious in those days before we actually had an orbiter around the place. The contrast between what we could see then and what we would soon see up close was exciting. I was convinced we were about to go to these worlds and learn their secrets. Then came Pioneer, and Voyager, and Cassini.

And, of course, Dawn. As we discover more and more about Ceres, the process repeats itself, as it will again when New Horizons reaches Pluto/Charon. Below is a page from a book called Picture Atlas of Our Universe, published in 1980 by the National Geographic. Larry Klaes forwarded several early images last week as a reminder of previous depictions of the main belt’s largest asteroid, or dwarf planet, or whatever we want to call it. Here the artwork isn’t all that far off the mark for Ceres, though Vesta would turn out to be a good deal less spherical than predicted. No mention of a possible Ceres ocean in the depictions of this time; all that would come later.

The recent Dawn imagery has us buzzing about the two bright spots on Ceres that, of course, were unknown to our artist in 1980. From 46,000 kilometers, all we can do is admit how little we know, which is more or less what Andreas Nathues, lead investigator for the framing camera team at the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research (Gottingen) does:

“The brightest spot continues to be too small to resolve with our camera, but despite its size it is brighter than anything else on Ceres. This is truly unexpected and still a mystery to us.”

Chris Russell, principal investigator for Dawn, speaks of a possible “volcano-like origin” of the two bright spots, but adds that we have to wait for better resolution to make any serious geological interpretations. The wait won’t be all that long (for better resolution, at least) given that we’re just days away from entering orbit on March 6. Could there be a better approach to this small world than this one, already focusing on something no one had expected to see?

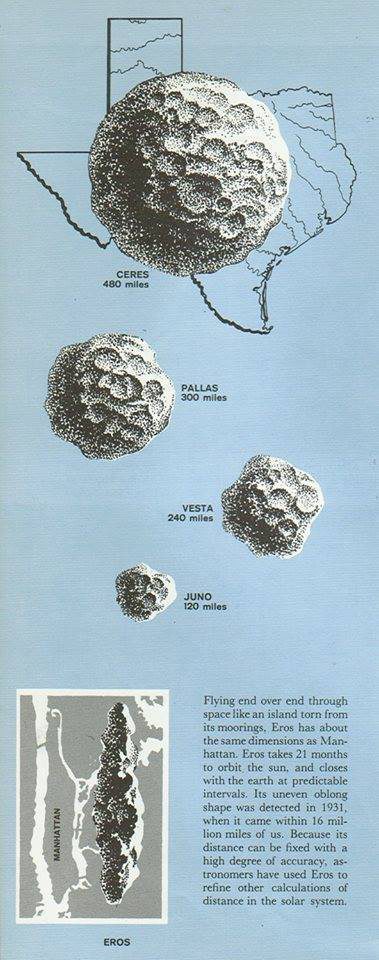

In 1961, in an illustration from The Universe (New York: Morrow), we find Ceres again displayed with companion objects like Vesta and Pallas (I’m afraid I don’t know the name of the artist). Here the round, cratered Ceres is reasonably accurate, and you’ll note the size comparison, with Ceres tucked up inside Texas. At the bottom of the image is Eros, shown here as an object the size of Manhattan and described in the caption as “Flying end over end through space like an island torn from its moorings...”

And here is Eros as it appeared in the Astronomy Picture of the Day in 2001.

When we get cameras in the vicinity of objects that for so long were just smudges in even the best telescopes, we sometimes find ourselves surprised and delighted, as witness the volcanoes of Io or, for that matter, the cryovolcanism and ‘canteloupe terrain’ on Neptune’s moon Triton. Sharpening the view takes us out of the realm of the artist’s imagination and into the world of concrete measurement. Giving up earlier visions can be poignant, as we learned with Mariner 4’s 1965 flyby of Mars, when a vegetative and even fertile Mars suddenly became a fantasy forever lost. But as Ceres is proving right now, the discovery of the unexpected is a much greater reward.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth