May 26, 2014

Will we find signs of tectonics on Pluto? And what would that mean?

This article originally appeared on astrobites and is reposted here with permission. Astrobites is a blog at which graduate students summarize and translate academic papers. This article is a summary of "Tectonic Activity on Pluto After the Charon-Forming Impact" by Amy Barr and Geoffrey Collins, submitted to Icarus.

It’s very cold in the outer solar system. Yet, studying the agglomerations of ice and rock far from the Sun is a smokin’ hot area of research. The newest kid on the block—2012 VP113, aka “Biden”—earned a lot of press because it, along with Sedna, another cosmic oddball, may have a story to tell about the very early history of our Solar System. But scientists haven’t forgotten Pluto, the O.D.P. (Original Dwarf Planet, hah).

In preparation for the New Horizons spacecraft‘s flyby of Pluto in mid-2015, people want to clarify the implications of possible observations. Of course, speculating now means discussing ideas that will ultimately prove incorrect. The alternative, however, is waiting until after the mission’s completion to think about the scientific details. Pluto will have everyone’s attention during the flyby, but this interest, alack, will probably dissipate (unless New Horizons gets, like, eaten). Scientists should maximize their window of opportunity—prepared to present a scientifically correct story for Pluto’s evolution alongside all the “gee whiz” photos from the flyby.

This paper, for instance, explains the scientific implications of pretty pictures of Pluto that show preserved features from ancient tectonic activity, like troughs, ridges, or bands. The authors conclude that such evidence would indicate that Pluto once hosted a global, subsurface ocean.

Tidal Evolution of Pluto and Charon

Pluto’s radius (~1,180 km) is ~70% that of Earth’s Moon. Charon, likewise, has a mean radius ~50% as large as Pluto’s. Pluto and Charon are in a unique orbital configuration, the so-called “dual-synchronous” state. That is, the rotational periods of Pluto and Charon are equal, and their rotational periods are equal to Charon’s orbital period. In other words, the same side of Pluto always faces the same side of Charon. (If you left Earth and our Moon alone for long enough, we’d eventually evolve to the dual-synchronous state, too.)

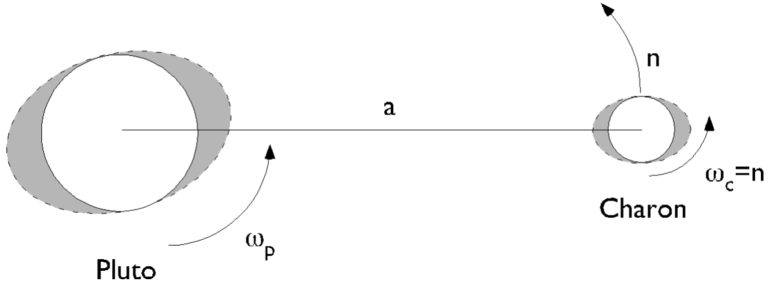

Pluto and Charon didn’t start in this configuration. Far from it, Charon was probably birthed from a giant impact. In its aftermath, Pluto was probably spinning rapidly and Charon was likely on a highly eccentric orbit. As shown in Figure 1, Pluto and Charon raise tides on each other, which raise bulges (highly exaggerated in this cartoon). These bulges exert torques on each other, rapidly circularizing Charon’s orbit and, more slowly, driving Pluto and Charon towards the dual-synchronous state.

Tidal bulges currently exist on both Pluto and Charon, but they are frozen in place, because the orbits of Pluto and Charon are no longer changing. But during their orbital evolution, tidal forces would have caused considerable stress to Pluto’s icy surface. The key question is whether this stress was large enough (greater than the yield strength of Pluto’s icy crust) to produce tectonic features that New Horizons could observe. The answer depends on the internal structure of Pluto during its orbital evolution.

Stress of Tidal Evolution Depends on Pluto’s Internal Structure

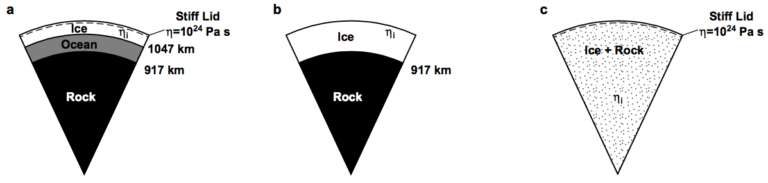

We don’t have much direct evidence of Pluto’s internal structure now, let alone information about its interior during its early history. As shown in Figure 2, the authors consider three possibilities. First, a simple model in which Pluto has an icy crust, a subsurface ocean, and a rocky core. The second model features a solid icy crust directly coupled to a rocky core. Finally, Pluto has uniform density in the third model; its interior is a homogeneous mixture of ice and rock.

The tidal evolution described above must have occurred in less than 4.5 billion years (the age of the Solar System). In general, fast tidal evolution requires large torques, which means big tidal bulges. A solid Pluto won’t deform much unless its interior has low viscosity from being heated close to the melting point of ice. Even with a hot interior, the tidal evolution is so slow that the icy crust is never deformed fast enough to produce tectonic features. With an ocean, Pluto and Charon quickly reach the dual-synchronous state, and we should see signs that the crust rapidly deformed. Evidence for an ocean, even an ancient one, on Pluto would shatter the perception that the outer solar system is frigid and lifeless. New Horizons' brief flyby may ignite years of intensive study of Pluto and other cold dwarf planets.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth