Leigh Fletcher • Feb 01, 2013

Saturn's Hexagon Viewed from the Ground

Editor's note: this was originally posted yesterday on Leigh Fletcher's blog and I thought it was awesome so I asked his permission to repost it. --ESL

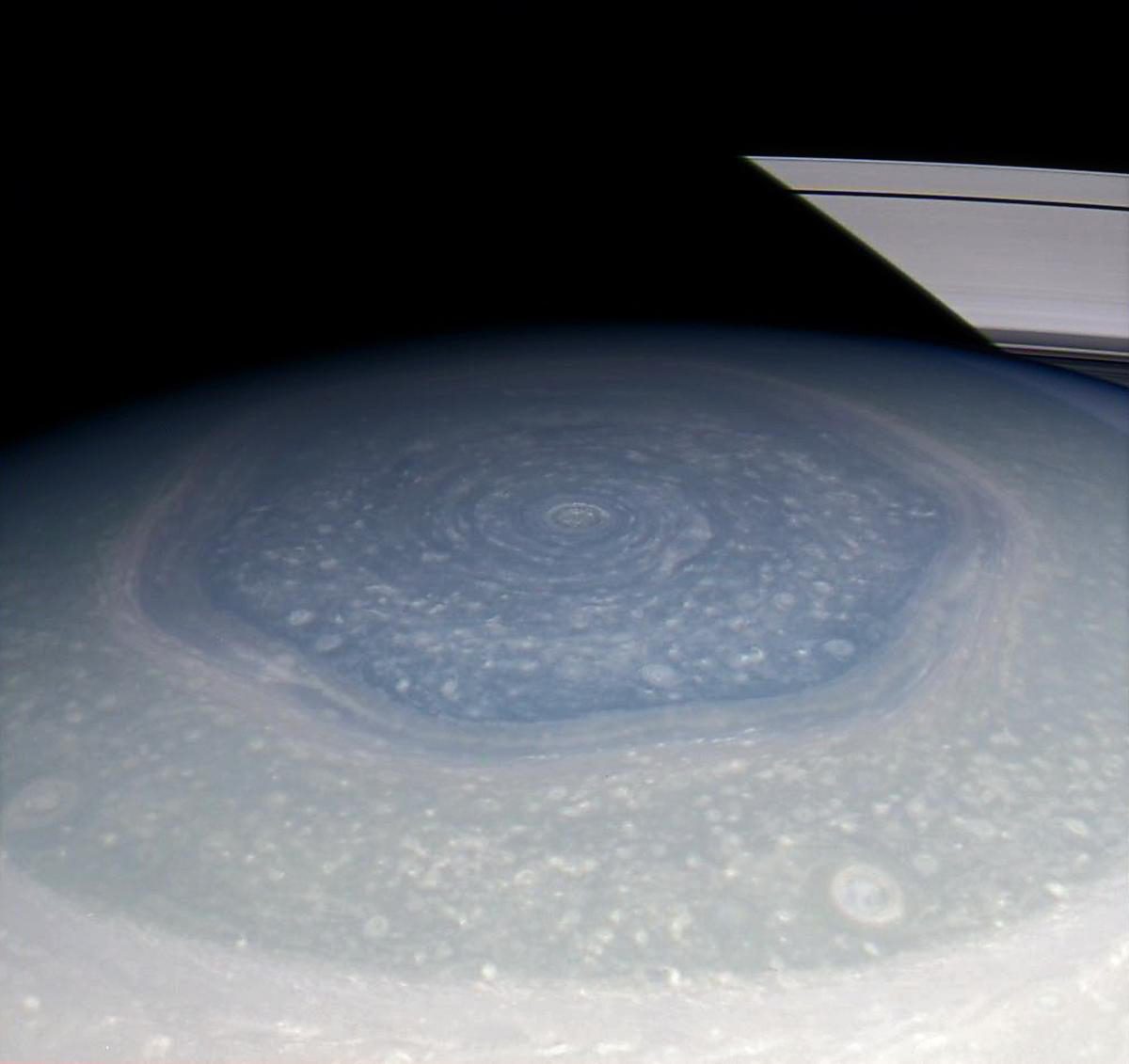

For the first time, amateur astronomers are capturing spectacular images of Saturn's bizarre north polar hexagon. Back in 2007, the Cassini spacecraft was in its first high inclination phase around Saturn, and gave us our first glimpse of Saturn's north pole, hidden from Earth's view in the darkness of winter. We used thermal infrared imaging from the Cassini/CIRS (Composite Infrared Spectrometer) instrument to measure the emission from the polar atmosphere, and observed the bizarre hexagonal wave feature that borders the north polar region at 78.7N planetographic latitude (Fletcher et al., 2008, doi:10.1126/science.1149514, and see the JPL story on 'Hot Cyclones on Both Poles of Saturn').

At the same time, Cassini/VIMS (Visual and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer) observed the hexagon in Saturn's deep clouds, also in thermal infrared light (Baines et al., 2009, doi: 10.1016%2Fj.pss.2009.06.026), showing that the wave is an extended feature from the deep clouds all the way up to the top of the troposphere.

This was a rediscovery of the hexagon, first observed in reflected sunlight by Voyager in the early 1980s (Godfrey et al., 1988, doi:10.1016/0019-1035(88)90075-9) and later in 1990/91 by professional astronomers using the 1.04-m diameter Pic du Midi observatory (Sanchez-Lavega et al., 1993, doi:10.1126/science.260.5106.329). Those reflected sunlight observations were in northern summertime conditions, whereas Cassini was viewing the hexagon during northern winter, confirming that this is a long-lived wave, present for at least a Saturnian year and relatively unperturbed by the relentless march of Saturn's seasons. The origins of the wave are still in doubt, and I won't try to cover the competing theories here (natural instabilities in Saturn's westward jets, interactions with large long-lived vortices, etc.).

Saturn passed through the northern spring equinox in August 2009, such that the north pole has been slowly emerging into spring sunshine ever since. In a talk at the Division of Planetary Science meeting in Reno last year, I pointed out that amateur observations of the planets have reached such a high quality that they would now be able to map Saturn's hexagon from a backyard telescope. We even talked about a competition for the first observer to do so, but we're too late!

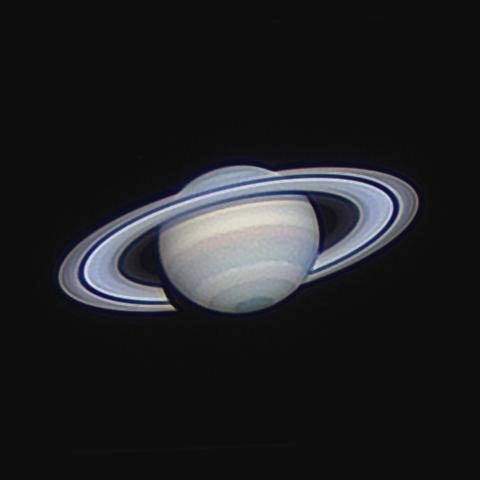

Although it's very early in the 2013 apparition of Saturn (i.e., it's still very low in the sky, particularly for European observers), husband and wife team Darryl Milika and Patricia Nicholas have been able to capture this stunning image of Saturn from down in Oz. In Darryl's words: "I’m really happy that I could be so lucky as to grab such an image of Saturn so early in the apparition…" Their observations were taken just outside a little hamlet called "Palmer" on the edge of the Murray Mallee, a wide belt of Mallee tree country bordering the Murray River about 1.5 hours from Adelaide.

They were using a Celestron C14, observing Saturn at an elevation of 51.8 degrees above the horizon. They were testing out a new CMOS-based planetary camera, ZW Optical’s ASI120MM, which has very high sensitivity and low noise, helping them to capture these crystal-clear images. Darryl tells me that they were very lucky to get these images, as clouds were racing in from the west and about to drown them out - they got one RGB set (and just a partial second set) before the clouds 'completely torpedoed their early-morning session'.

At the urging of users on the Cloudy Nights forum, they used the free WinJUPOS software to create a polar projection of his image, proving that they observed at least three, if not four, of the hexagon vertices.

This might not be the first amateur image of a hexagon vertex, but it's certainly the first amateur polar projection I've seen of this sort, and it's absolutely stunning. It certainly whets the appetite for what's to come in the next few months as Saturn reaches opposition in April. I expect we'll get plenty more hexagon images, and the next challenge is to map Saturn over a full rotation (maybe over sequential nights) to produce a complete map of the northern springtime pole!

Darryl said: "Personally I’m hoping for better seeing to go with the fact that Saturn will increase in size a couple of arcseconds, go from 0.6 to 0.3 magnitude and rise 20 degrees higher down here in Oz over the next 3 months." I, for one, can't wait to see the results, particularly as we'll be able to track the longitudinal locations of the vertices over time to determine how the hexagon is moving (some suggest it's completely stationary in 'System III' longitude).

While these efforts are underway on Earth, Cassini is back in high inclination orbits, and is taking the opportunity to gaze down at both poles using a broad variety of wavelengths (infrared included). Back in November 2012 we were treated to high resolution views of the north polar vortex and hexagon, described here. Cassini will continue to scrutinise the polar atmospheres for the next few years, through to the summer solstice in 2017, to see how all of these dynamic features vary over Saturn's year.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth