Mike Malaska • May 15, 2012

Earth�s toughest life could survive on Mars

The surface of Mars is a tough place to survive, but researchers at the German Aerospace Center (DLR) found some lichens and cyanobacteria tough enough to handle those conditions.

How tough is it on Mars? Pretty tough. First, the Martian surface pressure of 6 millibars is pretty much a vacuum compared to Earth’s surface pressure of 1000. 6 millibars of pressure corresponds to a point waaay up in Earth’s middle stratosphere about 35 kilometers above the surface. This is an altitude almost 5 times taller than Mount Everest and right about where altitude records for air-breathing jet airplanes are set. Next, you’ve got the harsh radiation from the Sun. On gentle Earth, much of the dangerous photon radiation from the sun is filtered out by Earth’s thick atmosphere. But on atmospherically-challenged Mars, energetic ultraviolet rays blast the surface. These rays could plow through an unprotected biological cell and wreak havoc on the critical information-carrying genetic material in the cell. If that weren’t bad enough, the rays can also smack constituents of the martian rocks and dirt and make some really nasty reactive chemical species that could chew up any cellular biological membranes not tough enough to resist. Finally, Mars is very dry and cold, dryer than the driest deserts on Earth. Any water might come in a brief morning dew that quickly evaporates as the temperature rapidly fluctuates. Life would have to struggle getting water quickly during these transient events then survive being freeze-dried for long periods of time.

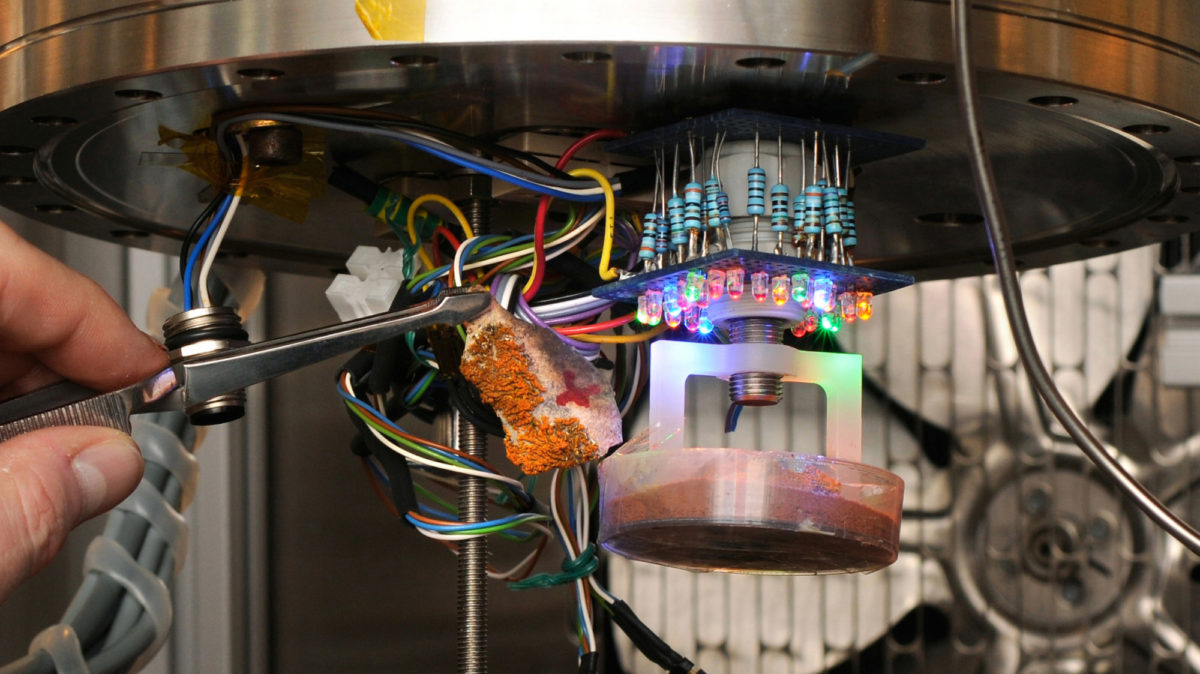

To see if they could find terrestrial life tough enough for Mars, the researchers collected specimens of organisms that were found in some of the most extreme and inhospitable places on Earth. They collected organisms from inside rocks, on mountain tops, and in the polar regions. These are places that might come closest to the environment on Mars. The researchers then created an environmental chamber that simulated conditions on Mars: ultraviolet radiation, infrared radiation, martian soil, low pressure, atmospheric mix, temperature ranging from -50 C to 23 C, the whole bit. They threw the collected specimens in the chamber to see if any could survive.

After a little over a month had passed, the researchers found that some lichen and cyanobacteria were still alive. Most surprisingly, the lichen and cyanobacteria didn’t just sit dormant, huddled down waiting for someone to open up the chamber and let them out; they were active. They sat in the martian chamber and took in simulated martian sunlight and made molecules and did all the things a living, functioning, active organism should do – they were happy!

So what are these things anyway and why does this matter?

Cyanobacteria are very important to the story of life on Earth. Cyanobacteria used to be called blue-green algae, but they are bacteria, not algae. While algae have a nucleus that has the information-carrying genetic material, cyanobacteria do not. Cyanobacteria have the genetic material distributed all over the inside of the cell, rather than specialized compartments. Cyanobacteria use molecules like chlorophyll, phycoerythrin, and phycocyanin to harvest light energy. It is the phycocyanin that gives the cyanobacteria the characteristic blue-green color. The light-harvesting compartments in algae and plant cells, called chloroplasts, may have originally started out as cyanobacteria that got incorporated inside the algae or plant cells. Cyanobacteria are special in that they can live in high-oxygen or low-oxygen environments. Importantly for us oxygen-breathing types, cyanobacteria may have been responsible for generating much of the oxygen in Earth’s early atmosphere. Fossil structures of cyanobacteria have been found that are over 2.8 billion years old. Cyanobacteria are primordial, and they changed our planet.

Lichens are incredibly tough. If you look around you will find them everywhere, on tree bark, rocks, walls, and on statues. Lichens exist as a form of a partnership of a fungal cell buddied up with a cyanobacteria or algae cell. The fungus forms the basic framework that incorporates the cyanobacteria or algal cell. The fungal cell provides protection, walls, structure, water storage, and mineral-gathering capability to the partnership. The cyanobacteria or algae cell, in turn, provides light-harvesting ability. This combination is famous for being able to survive harsh, dessicating conditions.

On Earth, lichens are one of the first things to colonize a bare rock surface. Lichens break down rocks and minerals so that other organisms can gain a foothold. Lichens are thought to have been one of the earliest things to colonize Earth’s barren surface over 400 million years ago. Lichens have also been found at high altitudes and in polar regions. These are just the kind of terrestrial environments that might be the closest match to surface environments of Mars. Both cyanobacteria and lichen are tough little pioneers. If you had to pick some organisms that might be able to survive on Mars, these might be the ones you’d champion.

So now we have examples of both cyanobacteria and lichens that could survive on Mars for at least a month. Does that mean that those types of organisms are there now? We don’t know. But it does mean that if life arose (or got transferred) to Mars, and managed to evolve into something as tough as cyanobacteria or lichen, then that life could still be there today and be perfectly happy. That’s encouraging, because it means that the habitability zone for life just got extended outward. This result applies to the martian environment but also extends to possible exoplanet environments as well.

As they say, life is tough; but it just got tougher!

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth