Emily Lakdawalla • Jun 19, 2019

OSIRIS-REx Sets Low-Orbit Record, Enters New Orbital B Mission Phase

Last week, NASA’s OSIRIS-REx asteroid sample-return mission announced that they had achieved an orbit above asteroid Bennu with an altitude of only 680 meters. For context, that’s only a bit taller than the second-tallest skyscraper, the Shanghai Tower, and lower than the height of the Burj Khalifa by 150 meters, according to Wikipedia.

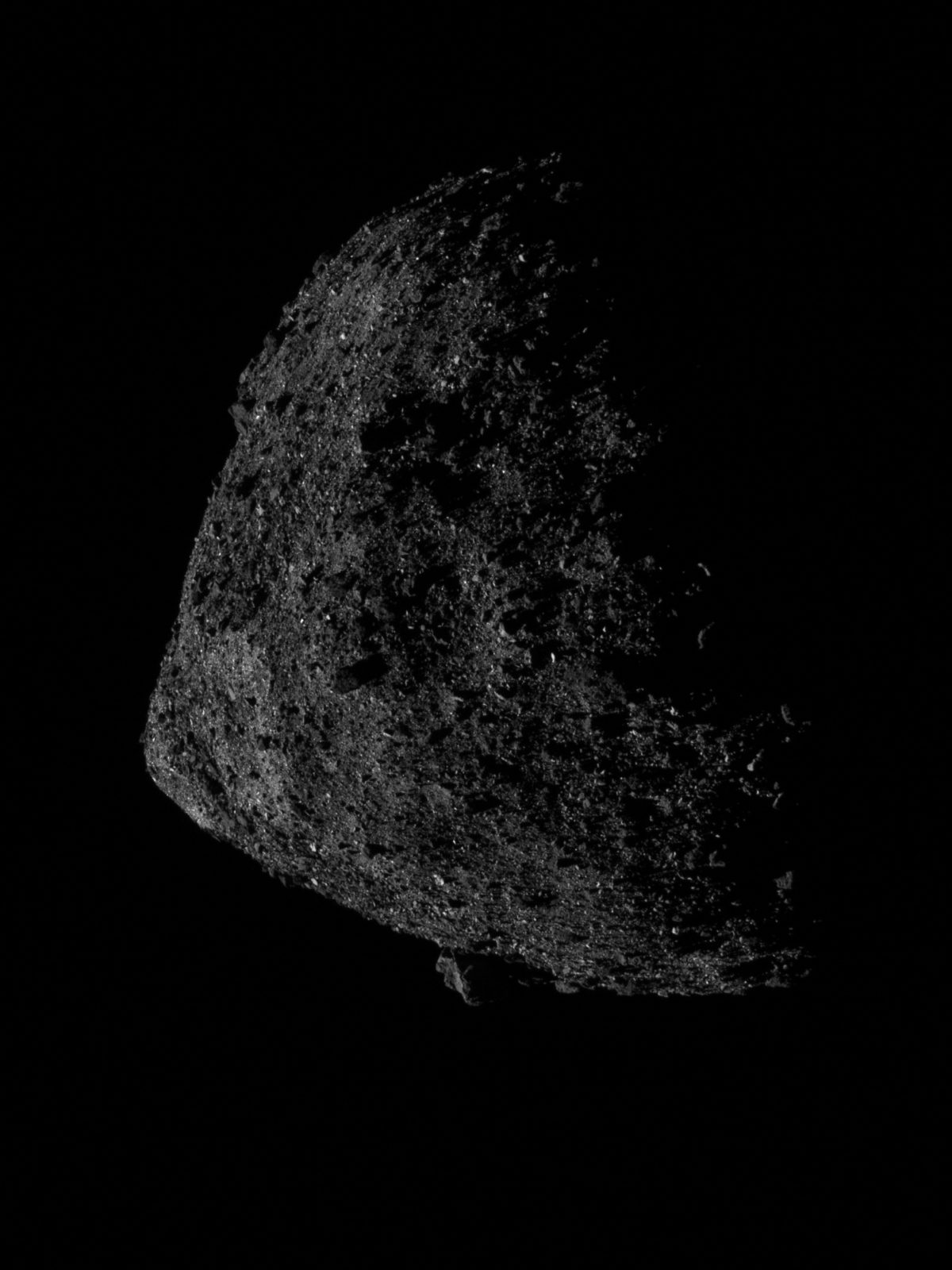

Although OSIRIS-REx’s altitude of 680 meters is low, you could still stick an entire second asteroid Bennu, and then some, between the spacecraft and the surface, because Bennu’s diameter is only 490 meters. From the new orbit, the spacecraft took a photo with its navigational camera. Here it is, as published by the mission:

I played a bit with orientation and contrast to produce the version below. Bennu is so very sharply rocky that I find it hard to produce an image that looks pleasing, at least when the asteroid is lit from the side like it is here. There’s so many shadows on all those angled facets of all those blocks that the image looks “busy” no matter what I do with it.

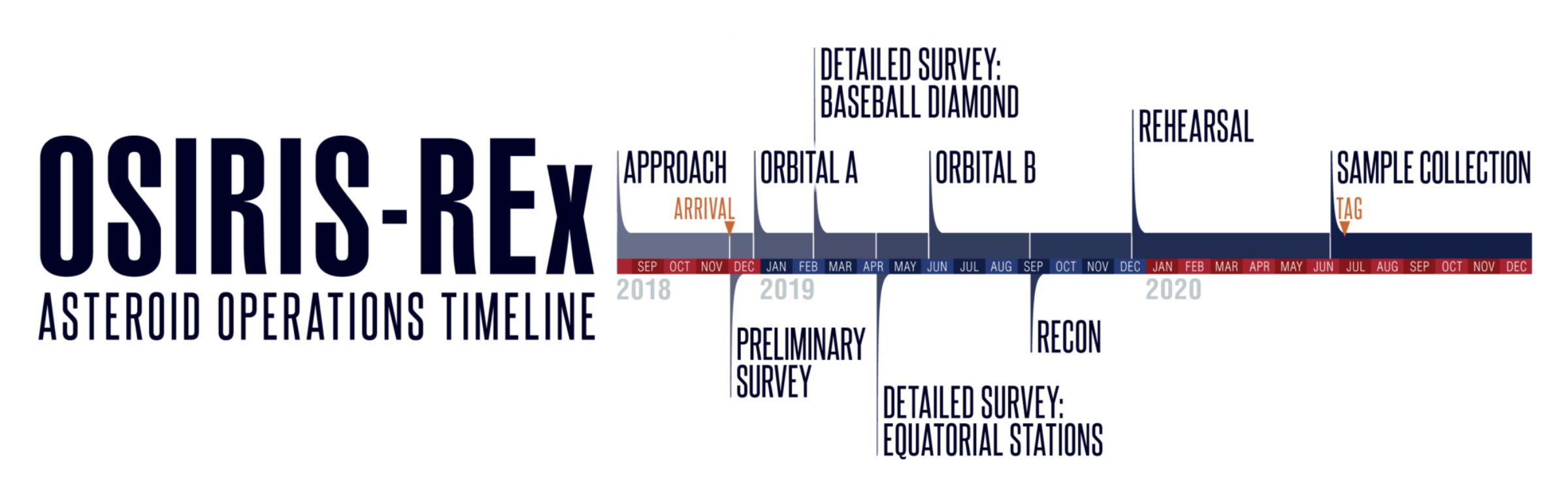

Why the low orbit? The lower a spacecraft flies, the more sensitive it is to subtle variations in the gravitational field. OSIRIS-REx needs to map these small lumps and bumps in gravity in order to be able to steer the spacecraft safely to a sample site next year. Also, OSIRIS-REx’s laser altimeter works best and gets the most detailed maps at lower altitudes. This orbit phase—called Orbital B—is therefore all about gravity and topography, though of course the other instruments will ride along, gathering data, especially over potential landing sites. By the end of this phase, in September, the mission should have selected two landing sites, a prime and a backup, and will go on to detailed reconnaissance of those two locations. (For more on the long-term OSIRIS-REx mission plan, read my anticipatory article from last year.)

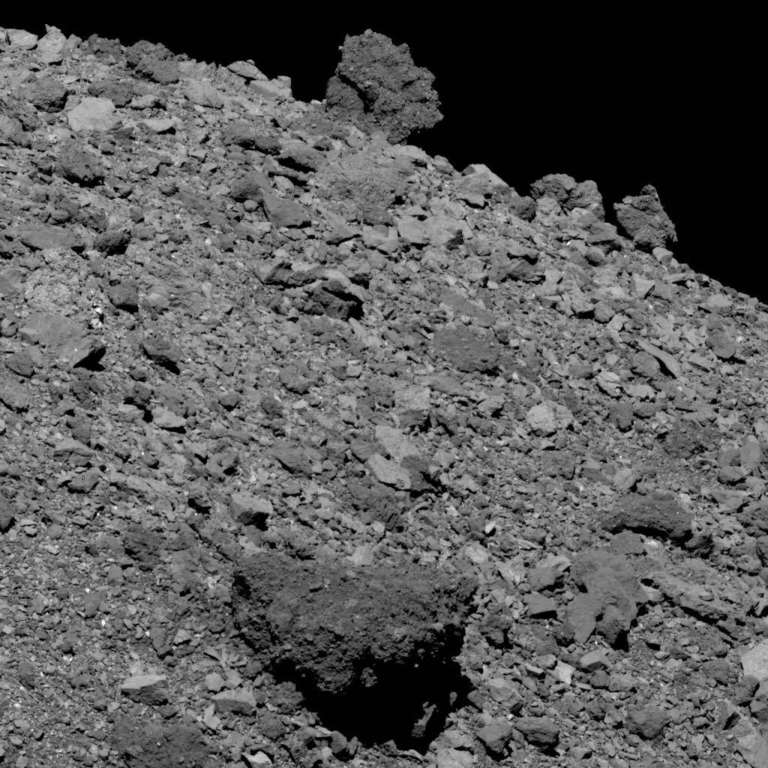

The mission has been regularly posting photos from earlier mission phases, when the lighting geometry was a bit better. I just love these views of gigantic boulders perched on the horizon. It’s possible to appreciate them aesthetically as well as like a scientist. How would a scientist look at these photos? Ask questions like: how varied are the boulder sizes? How varied are their shapes (angular or rounded), their reflectiveness (bright or dark), and their textures (monolithic, or made up of bits of other rock)? Do some of those differences trend together? Are there systematic variations, or are the varied boulders more randomly distributed? And, once in a while, even a scientist will ask herself: how cool is this, that we’re just a skyscraper’s height away from a bouldery asteroid that we’re preparing to land on? If you reeeeally like staring at Bennu’s boulders, you can help the mission out by mapping them! A citizen-scientist Bennu-mapping campaign is running through 10 July at Cosmoquest.

I’ll tell you the main thing I notice: many of the very darkest boulders also seem to be conglomerates, made up of other bits of rock. How I would love to hover by those boulders with a geologist’s hammer, using my pick to pry them apart and see what’s inside. It’s likely a mishmash of stuff from all over the ancient asteroid belt, jumbled up, thrown together, and tossed away, like an archaeological midden. Except instead of broken pots and animal bones, it’s broken asteroids and carbonaceous gunk and pre-solar-system dust.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth