Emily Lakdawalla • Jun 01, 2018

So you need questions answered about space

Hi! If you're reading this, you might be a student working on a school project about space. This is a great place to start. I’m a space expert -- at least, I’m an expert on robots exploring planets in our solar system. And I love to answer questions that are within my expertise. (Even if you're not working on a school project, but you do have a space question you can't find an answer to through the links below, please ask me and maybe I'll write a blog post about it. Do try Google first, though, I beg you.)

You probably already know that there is a lot of bad information on the Internet. Here are some good places that I recommend to look for answers to your questions:

Ask a librarian for help. This is what libraries and librarians are for! If they don't have your answers in books, they also know how to do Internet research. If you don't have a school library, try a public library.

Your teachers may or may not like Wikipedia, but I'll tell you a secret: I'm a professional and I use Wikipedia a lot. It's never my only source but it's a good place to begin.

NASA makes fabulous websites. Some are aimed at kids. Here is an index of all their websites for kids. Go there and hit Ctrl-F on your keyboard to search the page for your topic.

The European Space Agency or ESA has great stuff for kids, too.

Don’t want to limit yourself to kids’ websites? Another way to find great information on NASA or ESA sites is to use Google, but limit it to nasa.gov or esa.int websites. How? Let's say you want to learn about living in space. Go to google.com and type "site:nasa.gov living in space" or "site:esa.int living in space" in the search bar.

I’ve always liked the National Space Science Data Center’s very simple web pages with facts on solar system worlds and planetary missions. They look old but they’re regularly updated.

For beautiful photos, try NASA’s Planetary Photojournal and The Planetary Society’s image library. Images you find at both of these websites are OK for use in your school projects. Give credit to the source if possible.

Interviewing an expert

You might notice that my list doesn’t include emailing an expert to ask them questions. Your teacher may have told you to do that. Scientists and writers like me get a lot of these requests. Like, a LOT. Sometimes we have time to reply. Sometimes we don't. It's nothing personal. In fact, if you’re reading this it may be because you emailed me and I don’t have time to answer all your questions. Or because I’m not the right person to ask. If so, I’m sorry I can’t help you.

If your teacher insists you need to talk to an actual living scientist for a school project, please share a link to this page with them. Point them to the bottom of it, the part that is “for teachers”.

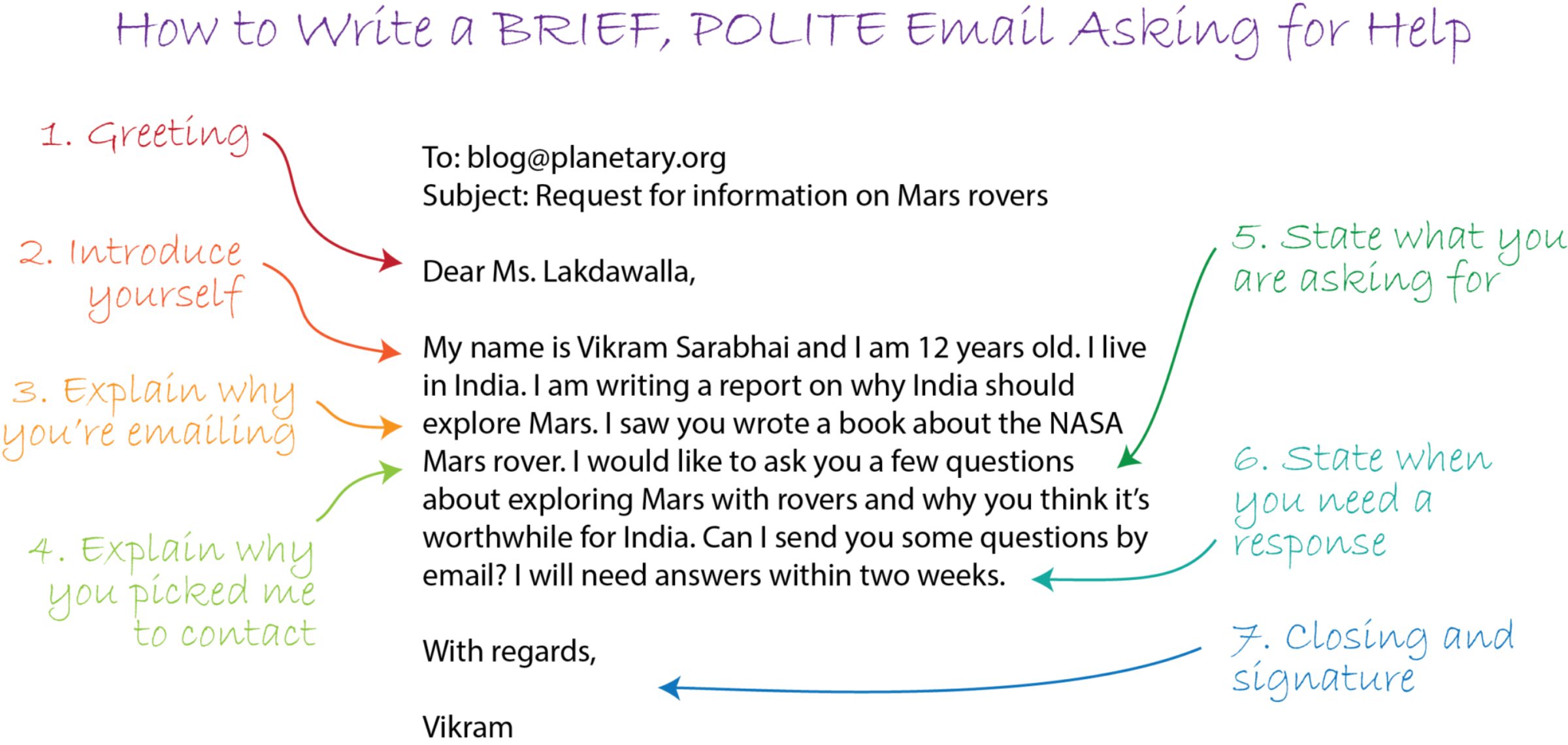

Here is my advice for asking a scientist to respond to your email. It’s mostly about good email etiquette, which is a skill worth learning. I can't guarantee it will work for you, but at least you will have learned a useful life skill!

Step 1: Greeting

Be respectful. Address the person by name. DON'T be too casual. Use their proper title ("Dr." is common for scientists). If you don't know the right title, just use their full name. If you don't have a name (maybe you are addressing an organization rather than a person), write "To whom it may concern:"

GOOD:

- Dear Ms. Lakdawalla,

- Dear Mr. Nye,

- Dear Dr. Betts,

- Dear Emily Lakdawalla,

- To whom it may concern:

BAD:

- Hiya,

- Hey there,

- To anybody who can help me,

- Emily,

- [no greeting]

Step 2: Briefly introduce yourself

Examples:

"My name is Sally Ride and I am in 10th grade at the Westlake High School for Girls."

"My name is Vikram Sarabhai and I am 12 years old. I live in India.”

Step 3: Briefly explain the reason you are contacting an expert

Examples (all from real emails I’ve received):

"I am doing a project on the challenges of space (radiation, space junk, no food for humans)."

"I am doing a project for space called Intergalactic Jury. It’s where groups plan a mission, then they present it, and at the end we vote on which one NASA should do."

"I'm doing a project called Genius Hour, where I have to research a topic of my choice. I am trying to find an expert on black holes."

Step 4: Say how you picked a person to contact

You're much more likely to get a response if you show you've done your homework -- that you worked to find an expert who has expertise in the thing you're asking them to talk about.

"I read your blog about Curiosity and I want to ask you questions about Mars rovers."

"I like your writing and would like to ask you questions about science communication."

"I read your Wikipedia page so I know you write about space."

Your teacher should help you find the right kind of expert.

Step 5: Politely ask for what you need, and Step 6: State when you need it

Be reasonable! The less you ask for, the more likely the expert will agree. Examples:

"I would like to send you five questions by email. I will need answers within two weeks."

"I would like to do a 15-minute phone interview some time in the next two weeks. I can do the interview after 3:30pm Central time on Mondays, Wednesdays, or Thursdays."

Make sure you give a reasonable amount of time for a response (not “TODAY!!!”). But if you give too long to respond, people may forget about your email. One or two weeks is a good amount of time.

Step 7: Close and sign politely

Examples:

- With regards, [your name]

- Thank you, [your name]

- Thank you very much for your time, [your name]

- Looking forward to hearing from you, [your name]

- Sincerely, [your name]

Step 8: Follow up

If the expert doesn't reply within a week or so, send one brief, polite follow-up email. Here is an example:

Dear [their name], I am writing to follow up on an email I sent to you last week. I know you are very busy but I am still hoping you will reply. Thank you for your time. With regards, [your name]

One follow-up is enough.

Step 9: Thank them

If the expert does respond, reply to thank them! Your thank-you note will make it more likely that other kids will get replies when they ask the same scientist for help.

Have a Backup Plan

A lot of the time, you will get no response. If nobody replies, please don’t take it personally. Scientists get a lot of email, and a lot of us are very bad at managing our email inboxes. Plan ahead what you will do if you don't get an answer to your email. If you don't know, ask your teacher.

You might try contacting several people at once. That’s fine. But don’t send a group email, send individual emails. And if you are lucky enough to get more than one response, follow through with all the responses. Respect people’s time!

For Teachers

The amount of email that scientists and science communicators get from students asking for help with school projects is a lot. These emails are usually very poorly targeted (I often get emails about human spaceflight, or terraforming Mars, or black holes, things I don't know very much about). They usually ask questions that can be answered better with an Internet search.

I love kids. I've been a science teacher to 9- and 10-year-olds. I love to talk to kids. I have kids of my own. I just don't have time to individually respond to all the emails I get with the wide-open questions they contain, yet it feels rude to respond to say "just Google it." Furthermore, asking children to email random experts with Googleable questions is not teaching them a skill that will serve them well as they grow. And it's not fair to kids to make a successful “cold call” be part of a passing grade. Moreover, as a parent, I'd have concerns about my kids being asked to contact strangers from the Internet. You can’t assume that everyone with a university email address is going to interact appropriately with kids.

I do think it's important for students to have an opportunity to see and interact with real-life scientists and other professionals. Some ways that you could do this more constructively would be:

You make the initial contact. Contact experts in advance of handing out the assignment to find people who are willing to give their time to your class before you have your students contact them.

If that's daunting for you, consider enlisting the help of a librarian to find and connect with appropriate experts.

Ask a single scientist to do an in-class visit through Skype or Google Hangouts (there are programs that help organize these visits, like Skype a Scientist). I gladly do these virtual visits and schedule an average of one outreach event every week.

I feel terrible about all the students I can't respond to, but there is only one of me to go around, and more requests than I am capable of fulfilling.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth