Emily Lakdawalla • Sep 15, 2017

Cassini: The dying of the light

Cassini is no more. At 10:31 according to its own clock, its thrusters could no longer hold its radio antenna pointed at Earth, and it turned away. A minute later, it vaporized in Saturn’s atmosphere. Its atoms are part of Saturn now – the lighter ones high in the atmosphere, the heavier ones (particularly the iridium-clad plutonium dioxide pellets that were, yesterday, in the center of its nuclear power source) likely descended much deeper before melting.

The news reached Earth, as predicted, at 4:55 in the morning, local Pasadena time. The world watched two graphs of radar signals, one from the X-band radio, one from the longer-wavelength S-band. The X-band signal dropped out first, at 11:55:39 UTC, and 11:55:46 for S-band. The S-band signal flatlined and then popped back up briefly, as Cassini’s antenna rotated off of Earth-point, bringing a side band briefly into view from the Deep Space Network. In all, the mission lasted about 30 seconds longer than predicted. It’s amazing to think that, across all that distance, into an atmosphere that had never been explored before, the engineers predicted the end that precisely. I’m not sure whether that extra 30 seconds was within the noise level of their predictions, or if it was a true overperformance of the spacecraft, or of the Deep Space Network’s ability to maintain lock on an off-pointed spacecraft. Probably a little of everything. Everyone was full of praise for the “perfect” performance of the spacecraft, down to the very end.

It was transmitting data all the way down. According to project manager Earl Maize, they are pretty sure the last data packet was from the magnetometer instrument. I talked with magnetometer team leader Michelle Dougherty about these last bits of data. She said it will be three to six months before they are able to report any results, but she’s hopeful they’ll finally be able to find an angular separation between the spin axis and the magnetic pole. She said that the data they have already tells them that angle is less than 0.06 degrees; with the final-plunge data, they’ll be able to find a separation as small as 0.015 degrees.

I could end the article there, because that’s all the news there is today. Of course today’s more significant than that. It’s the end of an era.

It’s a bit difficult to capture the mood here. It’s a veritable sea of emotions. Many of them are happy ones. The dominant emotion I sense from science and engineering teams is pride, the kind that makes your heart swell and your spine straighten. It’s been a good spacecraft. And the team got really good at operating it. The last, challenging proximal-orbit phase of the mission went off without a hitch. The science team is seeing new, exciting science from the last year, months, weeks, even the last seconds of the mission. Five minutes before the mission ended, the engineers conducted a final subsystems poll, and all got to report an engineer’s favorite status: “nominal.”

Of course, there’s sadness too. For many of us, it’s hard to imagine our lives suddenly lacking this spacecraft. Everybody here in the press room at JPL is using Cassini to measure their careers. Only a few here were professional science journalists covering space back in 1997 when Cassini launched. For most of us, the Cassini mission has been at Saturn for the majority of our professional lives. For me in particular, my professional science journalism career is precisely the same as the length of the Cassini mission to Saturn. I began writing news articles for The Planetary Society’s website when they asked me to begin covering Cassini as it approached Saturn.

Earlier this year, I traveled to be at the bedside of an uncle who was in the process of dying. It was a sad event but also fun to be with family, to have that family reunion, and reflect on the kindness of my uncle and retell his favorite stupid jokes. When he finally breathed his last, everyone knew it was time, and his was a life well lived. That’s how I have felt these last couple of days. I wish Cassini could function forever, but I know it can’t, and I couldn’t have asked for it to do anything more in its long mission.

At the moment of the end though, I felt something different and unexpected – anger. I thought of Dylan Thomas:

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

I was (and remain) angry that this great mission has ended. I suppose it’s just one of the stages of grief. And it’s good to be around friends in the media and on the science teams who are going through this grief together.

It’s commonly said that funerals are for the living, not the dead. If this is a funeral for Cassini, what consolation does it afford us? The end of a successful mission demands answers to the question: What now? What of the people who worked on the mission? What holes are left behind? What are we doing next?

First, the easy answers to those questions. The Cassini mission is technically not over yet, especially for the science team. They are funded for another full year to complete the process of validating and archiving every last bit of data returned by the spacecraft. This last year on missions isn’t just about archiving raw products. It’s also the time when science teams wrap up what are called “higher-level” data products – things like maps and mosaics, or calibrated or reprojected or otherwise processed versions of data sets. One hopes that science teams will be able to archive software or recipes for calibrating each instrument’s data, enabling future scientists to work with data that are as unaffected by instrument biases as possible. The science team is also, truth be told, relieved to no longer have the burden of planning new science observations; they can refocus on actually doing science with the data.

For the engineering and navigation teams, most of them have already migrated part-time to other missions, and JPL will absorb nearly all of them into other activities eventually. A chunk of the engineering team will remain at work for several months finalizing reports on spacecraft operations.

For us in the media, there’s certainly no lack of activity in the solar system at the moment. OSIRIS-REx will be flying by Earth in only two weeks. Curiosity and Opportunity are still roving Mars. And there are many more rather neglected spacecraft operating across the solar system (neglected, that is, in terms of public attention). There’s plenty of space to write about.

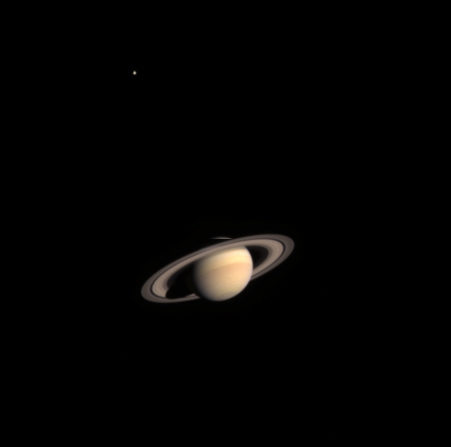

But a light has gone out. We haven’t traveled to Uranus and Neptune since the 1980s. Our horizon has now contracted again, to the distance of Jupiter’s orbit. (I’m not forgetting New Horizons, but its fast flyby of a small Kuiper belt object will be a brief and welcome flash illuminating an otherwise very dark region of the solar system.) That’s the kernel of my sadness. Out there, Saturn and its rings and moons will go on being awe-inspiring places. So will Uranus and Neptune and their rings and moons. Every image from Cassini and the Voyagers before it have been wonderful, and I’m sad about the loss of our window into the life of a giant planetary system.

There’s one consolation. Cassini returned half a million images. Every time I dip into the data archives I find something wonderful and fun to look at. A lot of scientists and journalists have spent this week sharing favorite images. I refuse to have favorites, and I haven’t indulged in that pastime this week. Instead, I plan to go right on diving into the data and sharing pretty pictures in the weeks and months to come, and I guarantee you that you will continue to enjoy surprising and beautiful vistas from Cassini. For that reason, it’s not over.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth