Emily Lakdawalla • Aug 24, 2015

Galileo's best pictures of Jupiter's ringmoons

People often ask me to produce one of my scale-comparison montages featuring the small moons of the outer solar system. I'd love to do that; I always start with Saturn's ringmoons, which have been pretty well photographed by Cassini, with the exception of Pan, at upper left.

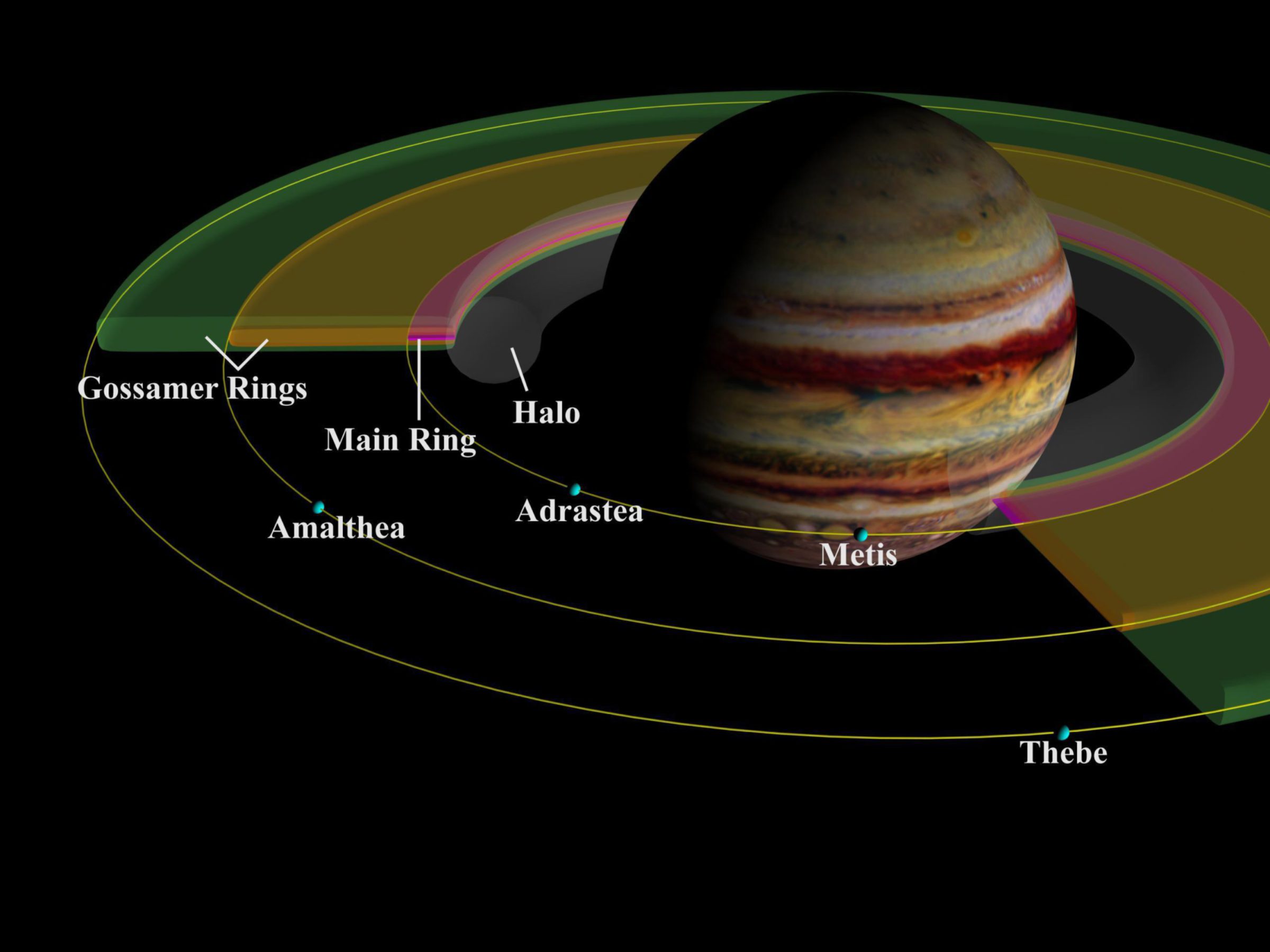

I love Cassini's crisp images. Unfortunately, Galileo doesn't compare very well for ringmoons. This is the very highest-resolution data that we have for Jupiter's four known ringmoons: Metis, Adrastea, Amalthea, and Thebe. I show the images at the same scale as the Saturn ringmoon comparison, above.

- Galileo imaged Metis from a distance of 292,600 kilometers, and a resolution of 2.97 kilometers per pixel.

- Galileo imaged Adrastea from a distance of 658,100 kilometers, and a resolution of 6.69 kilometers per pixel.

- Galileo imaged Amalthea multiple times. This is the highest-resolution image, taken from a distance of 237,700 kilometers, and a resolution of 2.42 km/pixel.

- Galileo imaged Thebe from a distance of 192,700 kilometers, and a resolution of 1.96 km/pixel.

The comparison isn't completely fair because for Galileo I'm showing you the data, warts and all; there is a lot of noise that needs to be cleaned up. Still the images are quite low-resolution compared to Cassini's; at this scale, you can see the blocky pixels. You won't commonly see them enlarged this way. Usually people enlarge them with subsampling, like in this Galileo mission comparison of four ringmoon photos. And those 11 pixels on Adrastea are often enlarged into a fuzzy blob.

Cassini's ringmoon images (with the exception of Pan) are much more detailed than Galileo's. Cassini has imaged most of Saturn's ringmoons at scales under a kilometer per pixel, many of them just a few hundred meters per pixel. Galileo's highest-resolution images of Jupiter's ringmoons have roughly 10 times lower resolution than Cassini's at Saturn. Why the difference?

Your first guess might be that the cameras had different resolution power, and you'd be partially right. Cassini's Imaging Science Subsystem Narrow-Angle Camera (ISS NAC) is one of the sharpest eyes that has been sent to the outer solar system, with an angular resolution of 6 microradians per pixel; Galileo's Solid State Imager (SSI) has a lower 10.16 microradian-per-pixel resolution. (The sharpest eye in the outer solar system is New Horizons' LORRI, which sees 4.94 microradians per pixel, although it has a wider point-spread function that gives its images a slight blurriness compared to Cassini's. The blur can be corrected with software.)

Angular resolution is only half the battle when it comes to obtaining sharp images of small objects. You can also make a small moon span more pixels by getting relatively close to it. The image montages that I am showing above have an identical scale, 500 meters per pixel. Cassini's camera can achieve that resolution by flying within 83,000 kilometers of a target; Galileo had to get within 50,000 kilometers to do the same. Cassini has taken photos within a few tens of thousands of kilometers of nearly all of Saturn's regular satellites except for Pan and Atlas.

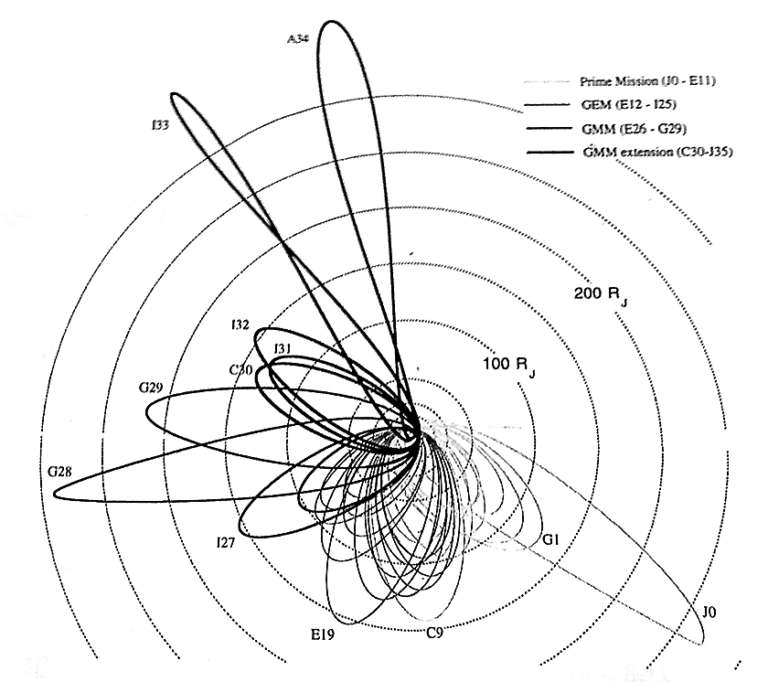

Sadly, Galileo never really had a chance to do the same. Jupiter's radiation environment is harsh, and it's worse the closer you are to Jupiter. Like Cassini at Saturn, Galileo performed an orbital tour at Jupiter that consisted of a series of highly elliptical orbits, but Galileo had to stay a lot farther from Jupiter than Cassini does from Saturn.

Galileo's best opportunity to image ringmoons happened at periapsis, when Galileo was closest to Jupiter. For most of its mission, Galileo's periapsis occurred at a position close to Europa's orbit, which is at 671,000 kilometers from the center of Jupiter. Thebe's orbit is at 222,000 kilometers; Amalthea is at 181,000 kilometers; Adrastea is at 129,000 kilometers; and Metis is at 128,000 kilometers. With an orbit periapsis near Europa's orbit, Galileo could never get closer than about half a million kilometers away from any of the little moons -- ten times as far as I need to make a montage of pictures matching the resolution of the one I made for Cassini's.

Late in Galileo's operational life, NASA performed an Io campaign, lowering the orbit periapsis and taking a calculated risk to spacecraft health for the payoff of close-up images of Io and a final gravity flyby of Amalthea. Io's orbit is at a distance of 421,000 kilometers from Jupiter's center, substantially closer to the ringmoons. It was on one of these orbits that Galileo got its highest-resolution images of Metis, Amalthea, and Thebe, our best looks ever at these moons.

Ringmoons are generally not a high-priority target for Jupiter missions. Cassini has collected an enormous data set on the behaviors of moons and rings; Jupiter's will be much harder to study. Juno is our next mission to Jupiter, and it will be orbiting very, very close to Jupiter, inside the orbits of all the ringmoons at just 5000 kilometers above the cloud tops. So it could, in theory, get close enough to the ringmoons to get better pictures -- if it had a camera like Cassini's or Galileo's. But it doesn't. It has Junocam, which will give us amazing views of Jupiter's poles and close-up images of its cloud tops; but, optimized for imaging giant Jupiter, the ringmoons will mostly remain just specks. Let's hope that either ESA's JUICE or NASA's Europa mission will be able to show us a little more of the personalities of these tiny moons!

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth