Emily Lakdawalla • Oct 16, 2015

Filling in the Enceladus map: Cassini's 20th flyby

A couple of days ago, Cassini flew past Enceladus for its 20th targeted encounter. Cassini has seen and photographed quite a lot of Enceladus before, but there's still new terrain for it to cover. Saturn has seasons just like Earth does, except they take much longer. When Cassini arrived at Saturn in 2004, it had just passed the southern summer solstice, so the south poles of Saturn and all the moons were bathed in continuous sunlight while large areas of their northern poles were in shadow. The equinox happened in August, 2009, bringing sunlight to the north poles for the first time in a decade. Even then, the sunlight barely reached the polar regions, throwing long shadows that obscured the terrain. It's only now, late in the mission, that Cassini is getting a good look at Enceladus' north pole to compare to earlier views of the south pole.

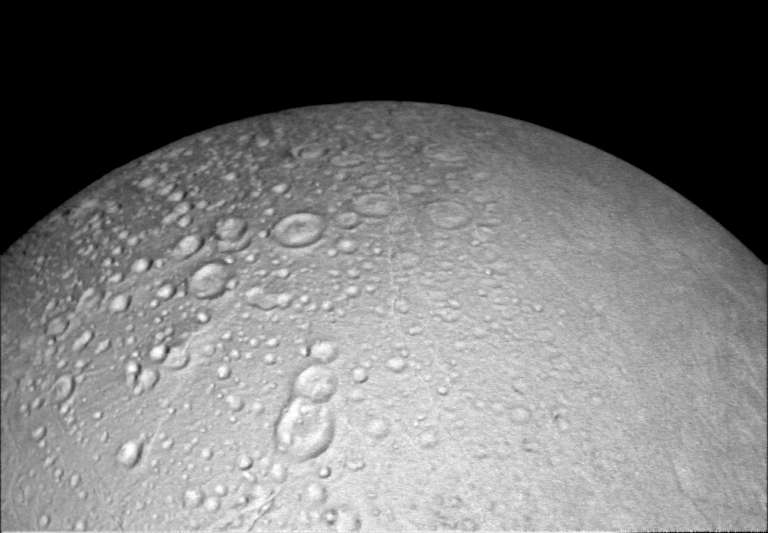

Here's a wide view of the north pole:

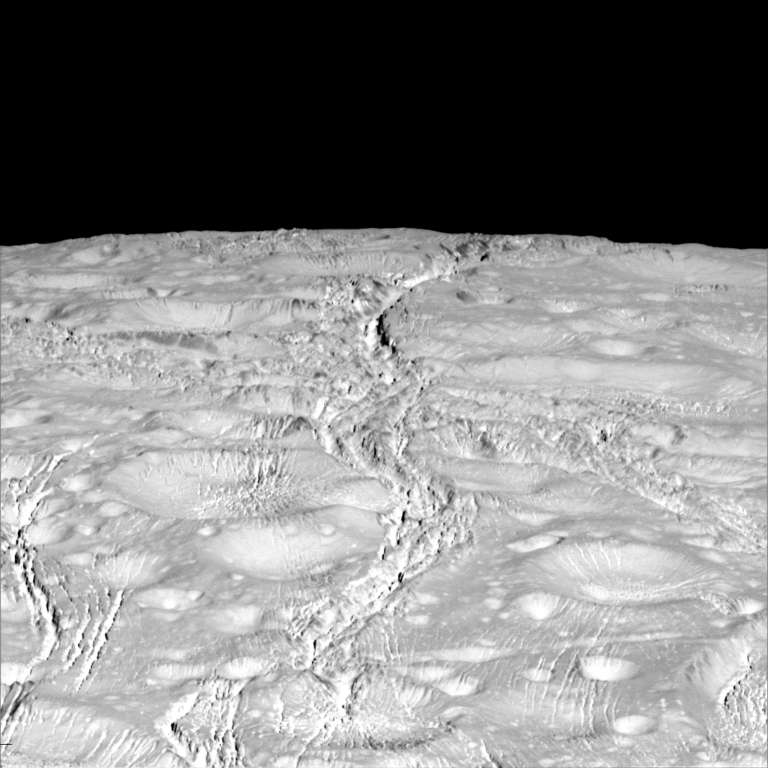

And here's a closeup. I'm intrigued by the slight differences in brightness along the walls of the craters and chasms. And it's puzzling how a terrain that's so heavily cratered could also be so thoroughly tectonized. There's been just enough tectonism to make its surface bizarre, but not enough to wipe out the moon's ancient history.

Back when Voyager 2 flew past Saturn, it, too, had a view of Enceladus' north pole. It was closer to equinox then, so less of the pole was visible. Voyager could see that there were a lot of craters, and that some of them had oddly humped floors, while half of Enceladus was craterless, enigmatically wrinkly.

Here is the best view we've yet had of a trio of those humped-floor craters on Enceladus. Cassini has seen these craters before, but never with the sun so high overhead, revealing all the subtle details. Again, I'm fascinated by the color variations in the walls of the smaller craters; I have no idea what those mean. The two largest craters here are Dunyazad and Shahrazad, and they have a complicated story to tell. That's fitting, because it was Shahrazad telling stories to her sister Dunyazad for 1001 nights that generated all the names for all the places on Enceladus. (Too bad we don't know the names of king Shahryar's previous thousand murdered wives to memorialize them with Enceladan craters. Shahryar has a crater, though.)

To get back to Enceladus: What stories are these craters trying to tell us? Notice that it's only the larger craters that have bulbous floors; the smaller the crater, the more ordinary it appears. That suggests that Enceladus' uppermost crust is quite stiff, but as you get lower in the crust, the ice is more and more able to flow over geologic time. If Enceladus were actually liquid, there would be no craters; liquid would flow in to fill the hole. What's happening here is that its ice is flowing at depth over geologic time, trying to fill in the hole, but the stiffer upper layer of the crust is resisting that. You wind up with a bulbous floor, and the stiff layer of crust over the floor has fractured as it has bulbed upward, making it crack polygonally.

But there's also something else happening that has little to do with the craters -- a regional network of fractures that maze across the surface. They are en echelon, meaning that instead of just one fracture, you have sets of parallel ones that march across the surface, each one offset a little from the last. That tells you of regional tension or shearing. What caused that? I don't know. Why is it so different from the southern half of Enceladus? I don't know.

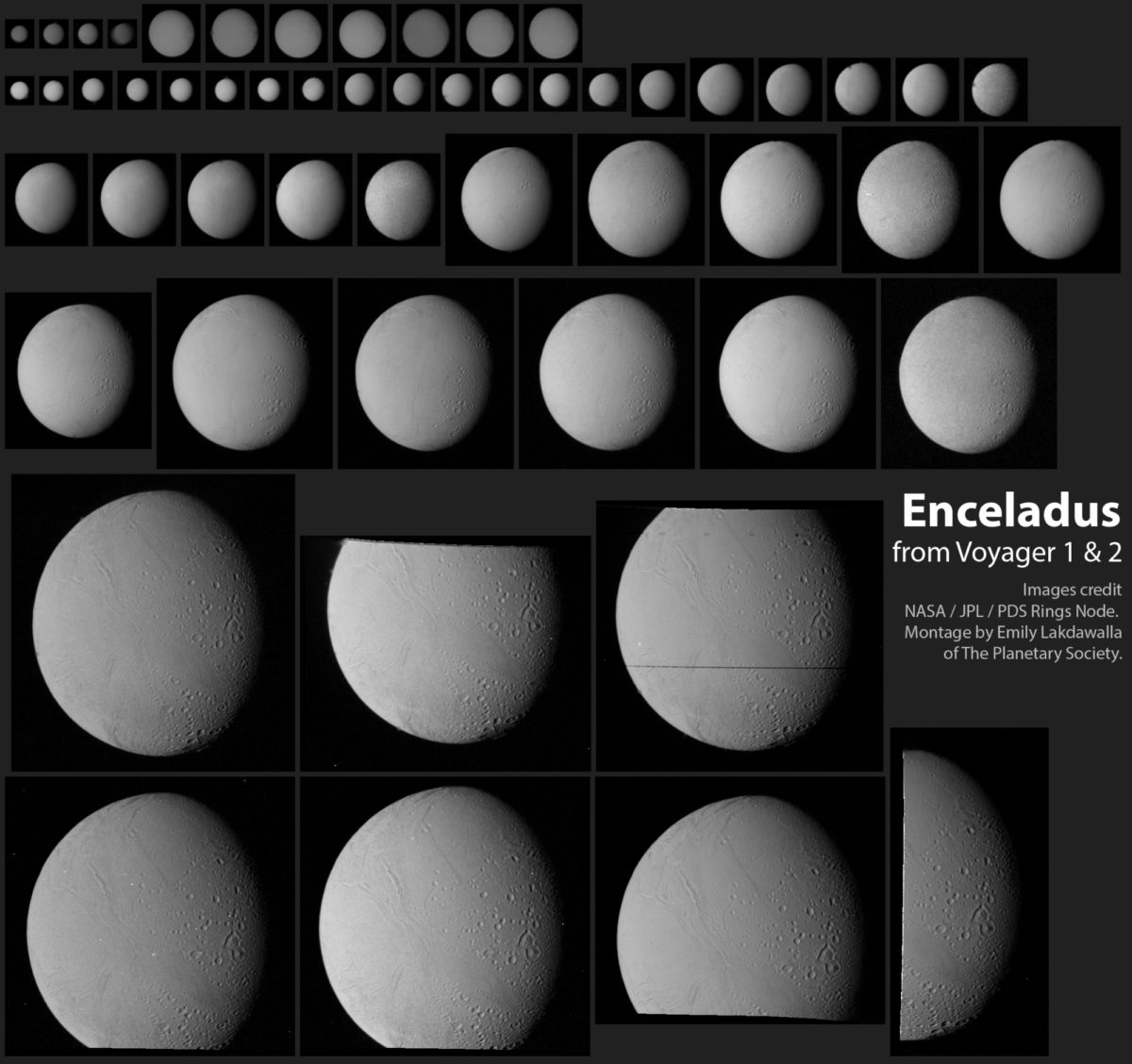

When the Voyagers flew past Enceladus, this is all we got for images from both spacecraft:

And here is what we got in just this one flyby from Cassini:

And remember, Cassini has done this 20 times, and has two more close flybys coming upon October 28 and December 19. As much as I love Voyager, there's nothing like the science you can get from a dedicated orbiter mission. We're going to be learning about Enceladus for decades, even after Cassini meets its end in 2017.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth