Emily Lakdawalla • Sep 17, 2015

Spectacular New Horizons photo of Pluto's hazes and mountains: How it was made

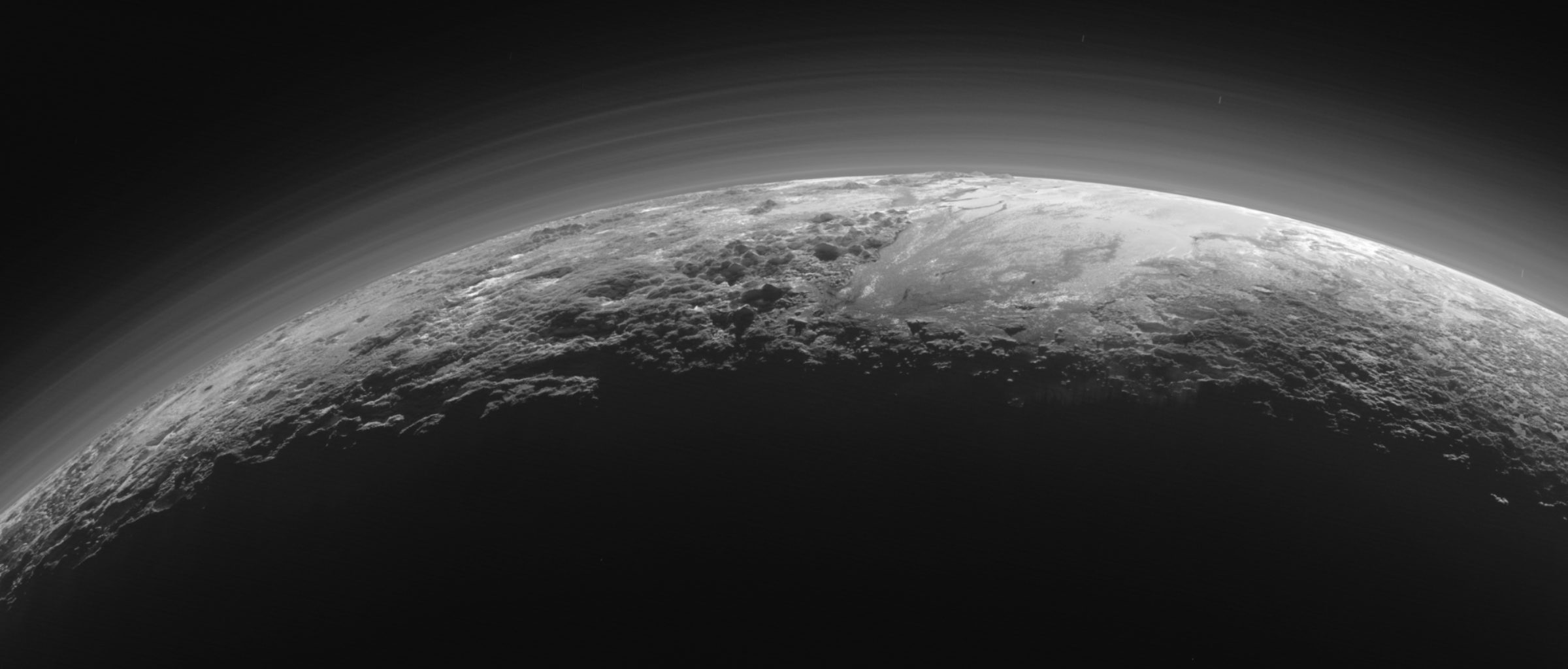

Before I write any more words, just gaze upon this image for a while. Make sure you enlarge it to its full resolution.

There are so many things to see. Look at all those haze layers! Or maybe it's an optical illusion, fewer layers with vertical waves that make them seem alternately thicker and thinner. Look at the pointy peaky mountains and how we can see into their shadows because of twilight. Look at the boundaries between rugged mountains and smooth plains. Look at the flow fields in the plains. Look at the mountains poised atop Pluto's curvature. You never see a view like that on Earth because Earth is so much bigger than its mountains; even the Moon is not so rugged. Look at the mountains casting shadows into Pluto's night. And just look, look, look at how much detail there is.

The NASA release accompanying this image does a great job explaining some of the features you can see in it, so I won't rehash that here -- go read it for yourself! Instead, I'll tell you more about how this picture was made, and why it's different from previous Pluto images you've seen.

The detail is there because this is a very large image. Nearly all of the Pluto photos we've seen so far are from New Horizons' Long Range Reconnaissance Imager, LORRI. The photo above is our first high-resolution view of Pluto from New Horizons' other camera, Ralph. Ralph itself is two different cameras; the one used for this photo is the Multispectral Visible Imaging Camera, or MVIC. I usually refer to MVIC as New Horizons' color camera, but that's a bit sloppy of me. Color isn't all that MVIC does, and it doesn't always do color.

LORRI is a simple camera to understand -- it's point and shoot. It is black-and-white, with a square detector, 1024 pixels square, over an extremely narrow field of view of 0.29 degrees. It has special optics designed to prevent distortion in the image. Choose how long you want the exposure to be (1 to 10,000 milliseconds), then point and shoot, and you have an image. Sometimes, to keep file sizes small and improve signal in low light situations, you can bin LORRI images 4x4, so the resulting pictures are 256 pixels square. That's pretty much it for LORRI.

MVIC is quite different from LORRI. Like many space cameras (including HiRISE and CTX on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and LROC on Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter), it is a pushbroom imager, meaning that instead of pointing and shooting, you sweep a linear detector array across a surface, building up a long, skinny image swath over time. It's sort of the same way that a photocopier or scanner works. The detector is 5024 pixels wide, of which 5000 are actually photoactive, so its images are 5000 pixels wide by an arbitrary number of pixels long.

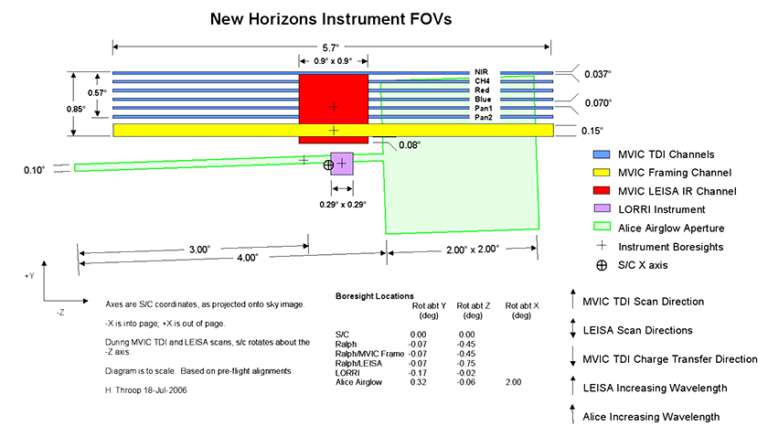

The 5000 pixels are spread across a 5.7-degree field of view. If you do the math you'll find that individual MVIC pixels are almost exactly four times wider than LORRI pixels, and MVIC images cover a field that is nearly 20 times wider than a LORRI image. So that big mosaic of Pluto that I posted on Tuesday, which took a 4-by-4 array of LORRI images to make, would occupy less than one-fifth of the width of the MVIC field of view. Here's a diagram that shows how all the fields of view overlap on the sky.

Typically, pushbroom imagers don't actually have any moving parts to sweep the detector across the surface. The Mars and Moon imagers I mentioned earlier use the spacecraft's orbital motion (which is very fast and happens at a nearly constant speed because of the circular orbits) to sweep the detector across the surface. For New Horizons, they actually rotate the whole spacecraft to sweep the MVIC detector across the target of interest.

Using spacecraft motion to build up an image introduces a problem. If your spacecraft is moving very fast, you don't get very much time to expose the detector to the scene. And if the scene is dark, there won't be many photons around to hit the detector in the limited time that you have. New Horizons has to move fast, and there is not much light at Pluto. One line of pixels just is not enough to gather enough light fast enough to make a well-exposed image.

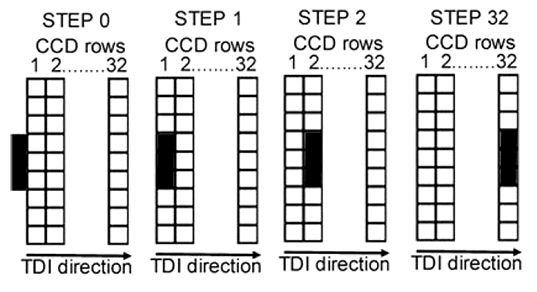

Time-delay integration comes to the rescue. MVIC's panchromatic detector -- the black-and-white detector that was used to capture the image in this post -- is 5000 pixels wide and also 32 pixels tall. When Ralph starts taking an image, it exposes the whole 32-pixel-tall detector. The spacecraft tells Ralph how fast it thinks it's rotating, and Ralph uses that information to determine how long it takes one row of pixels to move along the target. As spacecraft rotation carries the detector one pixel's worth of distance along the scene, MVIC dumps the charge accumulated from one row into the next one, and continues building up signal from the same spot on that next row. This repeats 30 more times before the accumulated charge is dumped into another CCD, called a readout register. The end result is that they can expose the image 32 times longer than they would be able to without time-delay integration.

MVIC actually has six of these 5024-by-32-pixel detectors. The one I described already makes up MVIC's "panchromatic," channel, which sees the full spectrum of light that the MVIC detector is capable of detecting, with wavelengths of 400 to 975 nanometers. There is a second panchromatic channel for redundancy (insurance against the failure of either one of them, or of either one of two redundant sets of Ralph's electronics). The other four detectors have filters in front of them, limiting the light that reaches them only to certain wavelengths. One has a blue filter; one has a red filter; one has a near-infrared filter; and one has a methane filter. Because they see less light (it's filtered), they may rotate the spacecraft more slowly to take color MVIC imgaes, allowing longer integration time on each pixel. Finally, Ralph has one more channel, the framing channel, which is 5000 by 128 pixels in size and operates like a more traditional framing camera. Its main purpose is to be available for optical navigation in the event that LORRI fails. (You need a lot of redundancy for a long-duration mission like New Horizons.)

Armed with all this information, I can now answer some questions about the image:

Question: If MVIC is New Horizons' color camera, why is this image black-and-white?

Answer: Either because only one channel was used to take this image, or because they have only received one channel's worth of data on the ground. To make a single color image, you have to downlink three photos, one each from three different channels; in other words, color images take three times as much data as black-and-white ones. As a matter of fact, New Horizons team member John Spencer has confirmed that only the panchromatic channel was used for this photo, because of the limited time and demands on the spacecraft during closest approach. If they were shooting in color, they wouldn't also be able to do as much with LORRI at the same time. I can't wait to see the LORRI images that were taken around the same time as this one!

Question: What are the short streaks in the sky above Pluto?

Answer: Those are stars. New Horizons was tracking Pluto while taking this image, but Pluto was also moving at the same time, so things in the background -- the stars -- got streaked.

Question: What is the banding in the dark areas of the image?

Answer: it's a periodic noise that comes from Ralph's electronics, which happens during readout -- something that also affects Cassini images. I'm not sure why it hasn't been removed in this image.

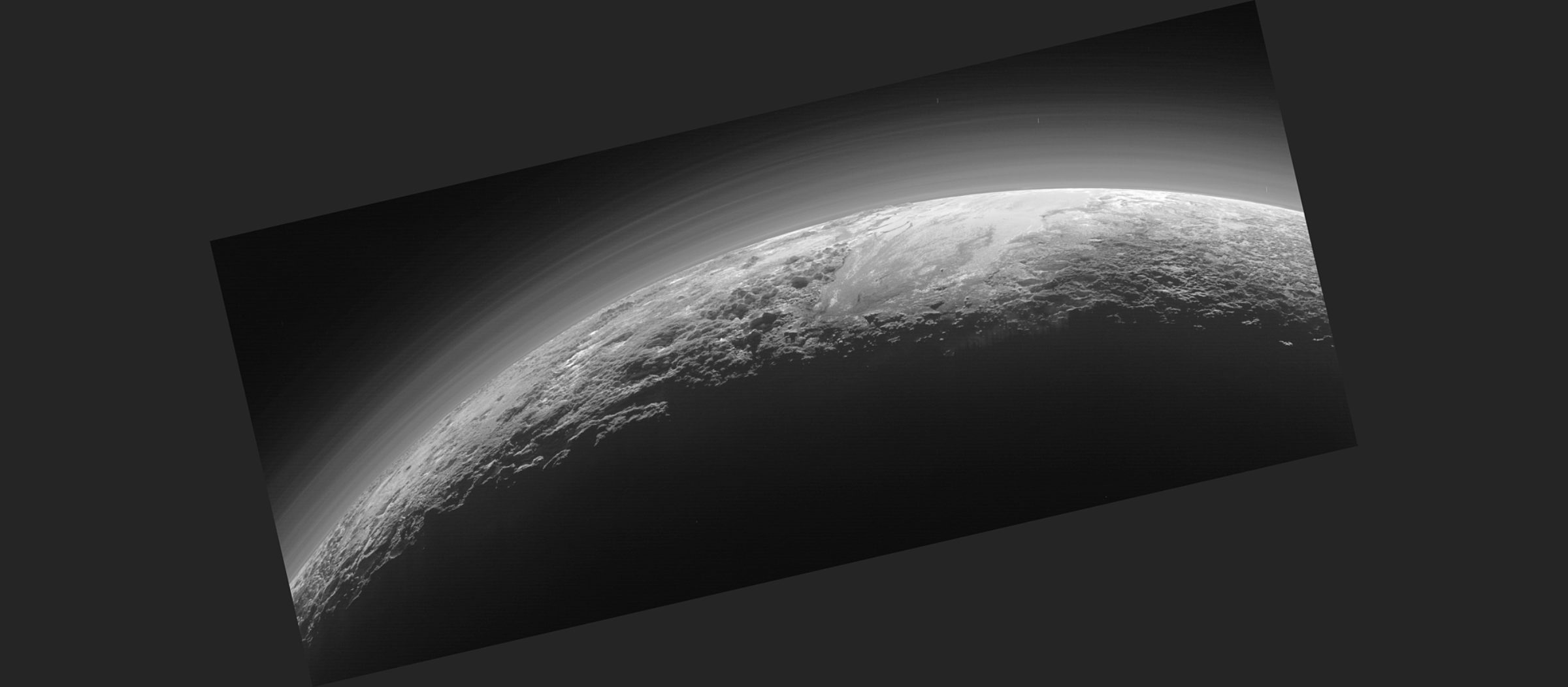

One curious thing about the banding is that it's not horizontal. That's a clue that the image has been rotated from its original orientation. Another clue that we're looking at just part of the original image is its size: 3420 pixels wide, less than the MVIC full width of 5000 pixels. So it's either been downsized or cropped. I've confirmed that it hasn't been downsized, only rotated and cropped. To give you a sense of how much more Pluto there would be in the original image, I've rotated the image to make the banding horizontal, and widened it to the full 5000-pixel width of the MVIC detector. The image may also be taller than this; there's no way to know how many rows it started out with. There's more Pluto yet to see!

Unfortunately, we won't be seeing the full image on the New Horizons raw image site on Friday. That's because only LORRI images are being rapidly released as raw data on the New Horizons website; MVIC images are not going to be released in the same way. So we will have to wait until the proprietary period is over to see the whole thing. I've been trying to understand when that proprietary period ends by reading the New Horizons Data Management and Archiving Plan (PDF) that was approved before launch. There are two planned releases of Pluto flyby data: the highest-priority ("Group 1") data come out early, and the lower-priority (Group 2 and 3) data come later. It looks like the archiving plan requires the first release of Group 1 Pluto flyby data two months after all of it is downlinked. In the original document that was estimated to be November 2015. Data from Groups 2 and 3 are supposed to come out in a second release 13 months after the flyby or 11 months after the end of the Group 1 downlink -- which would be July or August of next year. I'll see if I can get some clarity on this schedule from the mission.

Am I sad that I can't get my grubby fingers on these images right away? Maybe a teeny bit, but not very much. I can hardly keep up with the awesomeness of these images at the rate they're coming out. I'm glad that the fun of discovering new things on Pluto is going to be spread out over the next year. As long as the New Horizons science team doesn't tease me about what they can see that I can't, I'm happy to be patient.

Look out for #PlutoFlyby pictures coming soon - there are more and they’re [redacted due to embargo]. #sorryfortheteaser #awesome

— Carly Howett (@CarlyHowett) September 8, 2015Seriously, New Horizons folks, stop teasing.

OMG! Pluto never disappoints. Who said a picture=1000 words? I just saw a new one worth maybe 1000 scientific papers! #OMG #Plutoflyby

— NewHorizons2015 (@NewHorizons2015) September 13, 2015Argh!

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth