Emily Lakdawalla • Jun 25, 2014

Curiosity update: One Mars Year! Sols 662-670

On Monday JPL put out a press release marking one year since Curiosity landed -- one Mars year, that is! A Mars year has 669 Mars days (687 Earth days). Curiosity landed on sol 0. So the end of sol 668 marked one trip around the Sun for Curiosity's surface mission. There was some good stuff in this press release, including -- finally! -- the official version of Curiosity's self-portrait at Windjana, in all its colorful glory. It was worth the wait. The Malin Space Science Systems people really take care to get public products like this right, making a seamless composition. And they even composed it so that it works in portrait mode or cropped as a landscape image. Nice job. I imagine this'll be the cover of more than one book -- including, very likely, mine! If you don't understand how Curiosity took this photo (or why the arm doesn't appear in it), read my explainer on a previous self-portrait.

Mike Ravine at Malin Space Science Systems had some fun with the image data, making it into a movie (click for a full-res MP4):

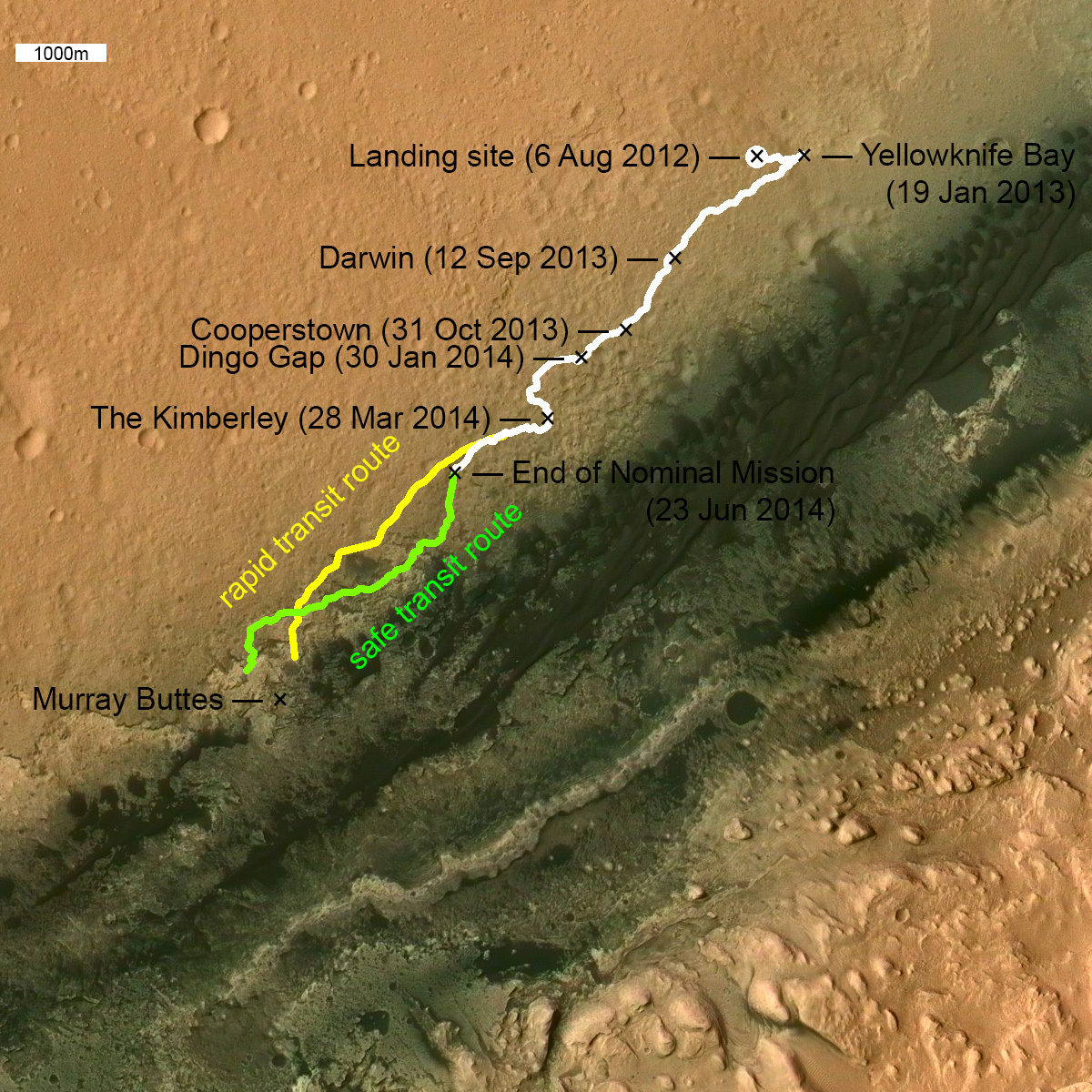

Another key image published along with the update is the new plan for the traverse toward Murray Buttes. A long time ago, on sol 376 (August 27, 2013), they published a map with a "Rapid Transit Route" that would take them from Yellowknife Bay to Murray Buttes. Initially, they followed that route quite closely; that was the period on the mission where they drove the fastest (until now, that is). But over the next few months, the wheels started to develop holes faster than they expected. They began taking frequent images of the wheels as they continued driving.

They decided they needed to change how they drove the rover. The Rapid Transit Route took them across high ground, which gave great views of the path ahead, but turned out to be wheel-chewing terrain, with bedrock sculpted by wind into pointy shapes that would neither crush nor roll away under the wheels. In their new plan, to save the wheels, they would instead drive in valleys that collected sand, and their drive over Dingo Gap into Moonlight Valley on sol 535 was the symbolic start of that new mode. They tested out this new driving mode, driving without using Autonav and with frequent wheel images, while they drove to the Kimberley. They reached the Kimberley on sol 581, and they spent another 50 sols reconnoitering the Kimberley and, finally drilling. In the background, though, there was an effort to replan the future route, because the original Rapid Transit Toute took them over terrain they now knew would be hazardous to the wheels. Yesterday, they posted a new overview map dated sol 663, with a "Safest Transit Route" marked that is substantially different from the Rapid Transit Route. Here's a map comparing the two:

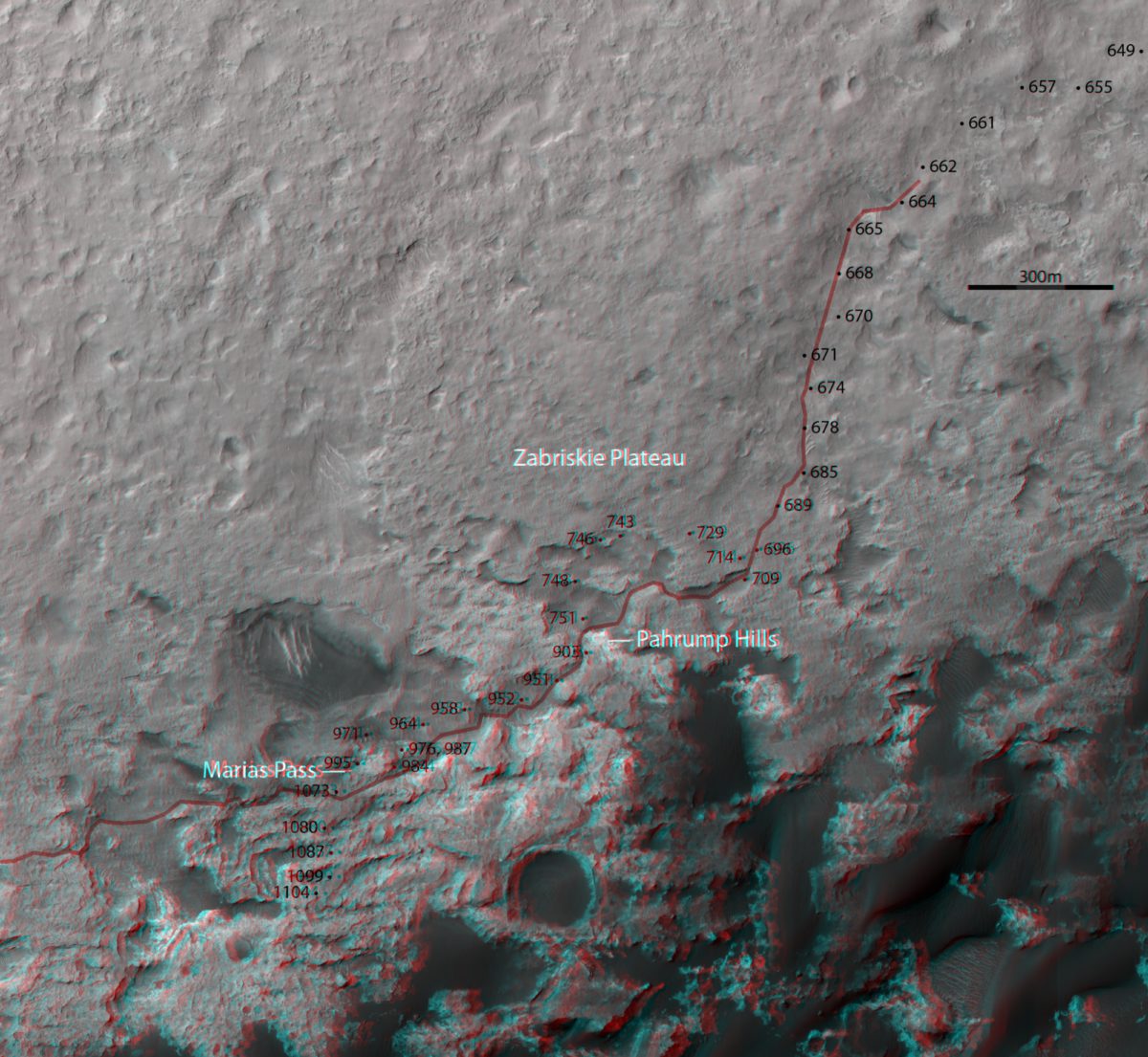

Let's look in detail at the new route. Here's my 3D route map, with the path to date marked in black dots and the planned future path marked in red. (Note: I will keep updating this map over time, so if you're looking at this long after I wrote it, you'll see a map dated later than this blog post.) They need to travel southwest, but there's a high-standing plateau of material that turned out to be the kind of stuff that shreds rover wheels. So now they're diverting south of it. The path goes mostly southward for about 600 meters until it gets close to the dark dune field. Then they'll begin to drive the rover through a region of valleys separating the plateau from the dune field. The valleys are cut into a relatively bright-looking rock, but if you look at the floors of the valleys you'll see they're dark and rippled -- it's flattish ripply sand, the kind of terrain Opportunity has been driving on for years. In most places, the ripples are transverse to the valleys, so Curiosity will be cutting directly across the ripple peaks, which is how Opportunity likes to cross ripples.

In fact, a recent drive ended atop a beautiful sinuous set of sand ripples. These are gorgeous. Just as important, they are too small to present any traction hazard.

But the ripples are plenty large enough to see from orbit. This gives you a sense of how well HiRISE can image the surface where Curiosity is driving!

Here's a neat video update talking about the testing they've been doing in the Mars Yard and in Dumont Dunes to make sure they understand how the rover will behave as the wheels continue to accumulate damage and as they maneuver among those sand ripples.

Here's some stills from the video, showing their new wheel testing rig -- it's basically half of a rover that runs in a circle, continuously. It reminds me of a horse on a lunge. Or maybe, given its deliberate speed, of the scene in Conan the Barbarian where Conan grows up turning the wheel.

I asked Ashwin Vasavada how the wheel wear testing was going and what their goals were. He said it was going well, and that they planned to run the rig until the wheels totally and completely cease to function to see exactly how they fail. In all their previous wheel testing, they haven't yet managed to wear down rover wheels to the point where they don't work as wheels anymore. They have a really banged-up set of wheels that is just like the ones on Mars except that they were used on "Maggie," the duplicate test rover on Earth -- which means they were subjected to about three times the weight that the wheels experience on Mars -- and those have suffered big tears and broken grousers (treads) and "they still function very well," Ashwin told me. "We don't know exactly how the wheels degrade to where they eventually fail. We already have confidence, based on testing so far, that the wheels perform really well at states that are much more damaged than where Curiosity is today, or where it is projected to be at the foothills of Mount Sharp." So at this point the wear testing that they're doing isn't relevant to today's operations; they're trying to learn whether and how wheel damage will affect them many years from now.

On Mars, he said, they were going to focus on driving on benign terrain to conserve wheel health as far as possible, and are pushing to drive as fast as is safe, using Autonav to take them beyond where they can see on any given sol. But of course they won't always be able to drive on safe terrain; there are short stretches where they'll have to cross more challenging terrain. In those places, he said, "we'll purposely slow down and pick a very careful path and limit the amount we drive, and also do wheel imaging at a higher frequency to see if we're actually incurring more damage."

Here's to speedy driving! They will hopefully be able to run fast for the next 600 meters or so, but it'll necessarily slow down once they drop into those squirrely valleys.

And now for some tidbits of science from the JPL update. There are the first reports from David Blake on the CheMin results at Windjana:

Preliminary indications are that the rock contains a more diverse mix of clay minerals than was found in the mission's only previously drilled rocks, the mudstone targets at Yellowknife Bay. Windjana also contains an unexpectedly high amount of the mineral orthoclase, This is a potassium-rich feldspar that is one of the most abundant minerals in Earth's crust that had never before been definitively detected on Mars.

This finding implies that some rocks on the Gale Crater rim, from which the Windjana sandstones are thought to have been derived, may have experienced complex geological processing, such as multiple episodes of melting.

Potassium feldspar on Mars is pretty surprising, at least to me. I associate potassium feldspar with granite and rhyolite -- two kinds of volcanic rock you get in continental crust on Earth, but not so much in basalt-rich oceanic crust. The fact that it's there could mean that Mars has had a more cyclical volcanic history than we have thought. But it's not the only possible explanation. Someone on Twitter pointed me to this article talking about potassium feldspar forming in hydrothermal environments on Earth -- that is, places where water interacts with volcanic rock. And we know there was a lot of water in the bottom of Gale crater. The problem with the analogy here is that the hydrothermal environment on Earth that made potassium feldspar was a place where there was hot water interacting with rhyolite. So you still have to make the rhyolite somehow, and you're back to requiring multiple episodes of melting. All very cool.

ChemCam principal investigator Roger Wiens has a lot more to say about this in the ChemCam team's abstract being presented at the 8th International Conference on Mars in a few weeks. They have found a lot of rocks containing large feldspar laths -- like this one, named Harrison, seen on sol 514 -- and seem pretty excited about them: "Aside from Gusev, Gale is by far the closest landing site to the southern highlands. While claims have been made in the past of more felsic compositions (Pathfinder, TES), the overall understanding of Mars has been that it had a largely mafic, minimally evolved crust. The Gale findings strongly suggest otherwise, but the extent of evolved magmas is still unknown." Also notable from that abstract: there was a circular feature that looked kind of like a fire ring just in front of Dingo Gap. When ChemCam zapped that feature, it found "one of the highest hydrogen signals of any rocks observed to date."

The APXS team is also trying to puzzle out the origin of the potassium-rich minerals, but have no conclusions yet: "K-feldspar may not be a primary igneous mineral. Authigenic K-feldspar can form from the action of brines on plagioclase. We might expect to see elevated Cl and Br if this were the case, which is not evident from the APXS data. The K-bearing phase could also be an alteration product after alkali feldspar, like illite. However, if this were the case we might expect to see an associated increase in the Al content of these rocks. Kalsilite, leucite, K-bearing zeolite, amphibole and biotite are also possible phases." And so on. This is science in progress; we have data from Curiosity's awesome instruments, but it's going to take time for scientists to figure out what we can learn from that data.

This kind of work is why I got in to geology. There's only a very little evidence, little peepholes into the past, from which geologists try to construct a whole planet's history. Figuring out a history that's consistent with the evidence is a kind of storytelling, a deeply creative -- and fun -- process. And it's only beginning on Curiosity.

Meanwhile, Curiosity is driving, driving, driving, on the way to different rocks that'll have little bits of a different chapter of the story. This will be my last update on Curiosity for a few weeks, as I'm going on vacation for the first two weeks of July and still traveling the week after that. I hope to find Curiosity's made a lot of progress on the path to Mount Sharp by the time I check in on the mission again!

A late addition to this post: Here's Phil Stooke's most recent Curiosity route map.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth