Emily Lakdawalla • Jun 05, 2013

Curiosity update, sol 295: "Hitting the road" to Mount Sharp

There was a Curiosity telephone conference this morning to make an exciting announcement: they're (almost) done at Glenelg and are preparing for the drive south to Mount Sharp. (View a recording here; visuals and press release are here.) Allow me an editorial comment: at last!

The briefing included project manager Jim Erickson; sampling activity lead Joe Melko; and deputy project scientist Joy Crisp. There wasn't much science discussed; it was all operational details. Here's a summary.

Here's what Jim Erickson said (I've mixed in some stuff from the Q and A portion of the conference). "We have completed almost all the first-time activities...the processes and tools are now verified by use, and the pace is really picking up." They are ready to drive toward Mount Sharp. The science team is poring over Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and Odyssey imagery to scout for future science stops, "to create a menu of possible stopping points." The total distance to be traversed from the current position to the entry point into the dune field that flanks the base of the mountain is about 8 kilometers. Engineers are scouting for vantage points from which they could achieve views of the discarded entry, descent, and landing hardware.

Melko gave a quick summary of the drilling activities at Cumberland. The Cumberland site was chosen as a good site for "dilution cleaning" of sample handling equipment. The actual act of drilling at Cumberland to a full depth of 65 millimeters only took 6 minutes -- within a few percent of the drilling time at John Klein. This is a good clue that the material is similar to that at John Klein. In other, harder rocks it could take up to 2 hours to drill to full depth. They collected 14 cubic centimeters of material from the drill hole, of which 6.5 cubic centimeters made it through the sieve. This was "in family" with the first drill sample. Here's a cool video of the drilling:

Curiosity drills into its second rock, sol 279 This sequence of images from the Front Hazard-Avoidance Camera on NASA's Mars rover Curiosity shows the rover drilling into a rock target "Cumberland" on May 19, 2013.Video: NASA / JPL

It took 11 days from arrival at Cumberland to delivery of sample to SAM and CheMin. This is three times faster that was achieved at John Klein. Actual drilling activity was four times faster. The entire campaign from arrival to departure took about exactly three weeks. Speed increases came from:

- using lessons learned from the first drilling campaign;

- use of the rover's autonomous self-protection capability, allowing them to string activities together and reduce the number of times the rover had to check in with engineers on Earth;

- and they rolled out new "cached-sample" capabilities, allowing the rover to wrap up contact science activities and begin driving with sample still on board, leaving the site before completing all sample analysis runs.

In Q and A, Melko said that science stops along the traverse that involve drilling will typically take two and a half to five weeks.

Joy Crisp talked about immediate science plans. Before they begin the trek to Mount Sharp, the science team wants to spend a few days each following up on three things.

- They want to complete a systematic DAN neutron spectrometer survey (both passive and active) across the geologic contact between the Sheepbed and Gillespie stratigraphic rock units. Sheepbed is the lowest unit in Yellowknife Bay, the unit that has been drilled at John Klein and Cumberland. "We saw a lot of water released when we heated the sample in SAM, and also CheMin detected abundant clay minerals." They want to see if there is systematic variation in hydrogen abundance across that contact to the coarser-grained Gillespie unit.

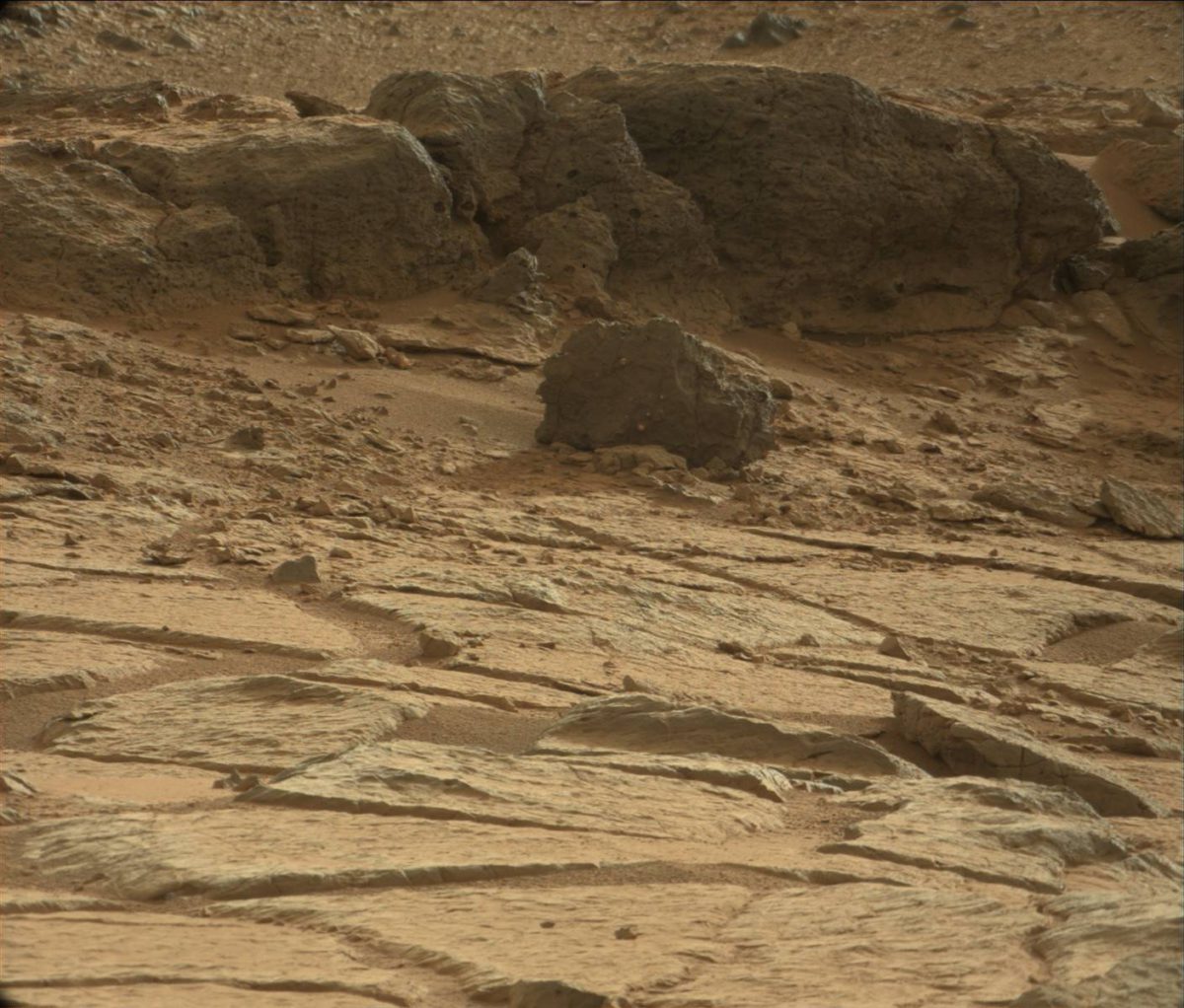

- They want to revisit Point Lake, a rock exposure with a unique, pitted texture that Curiosity has only viewed from a distance of about 25 meters. They want to do contact science and more imaging to determine its rock type. Its "Swiss-cheese" texture could indicate that it is volcanic, but it could also be sedimentary.

- And they want to revisit Shaler. Shaler is a wide exposure of "spectacularly cross-bedded rock that we think was probably stream-deposited. We want to go back to do paleo-hydrology, to study geometry of layers and structures to see how fast the water was flowing and what the water depth was." We also want to collect chemical data to compare Shaler to the other rocks.

Here's the view of that interesting, pitted "Point Lake" rock:

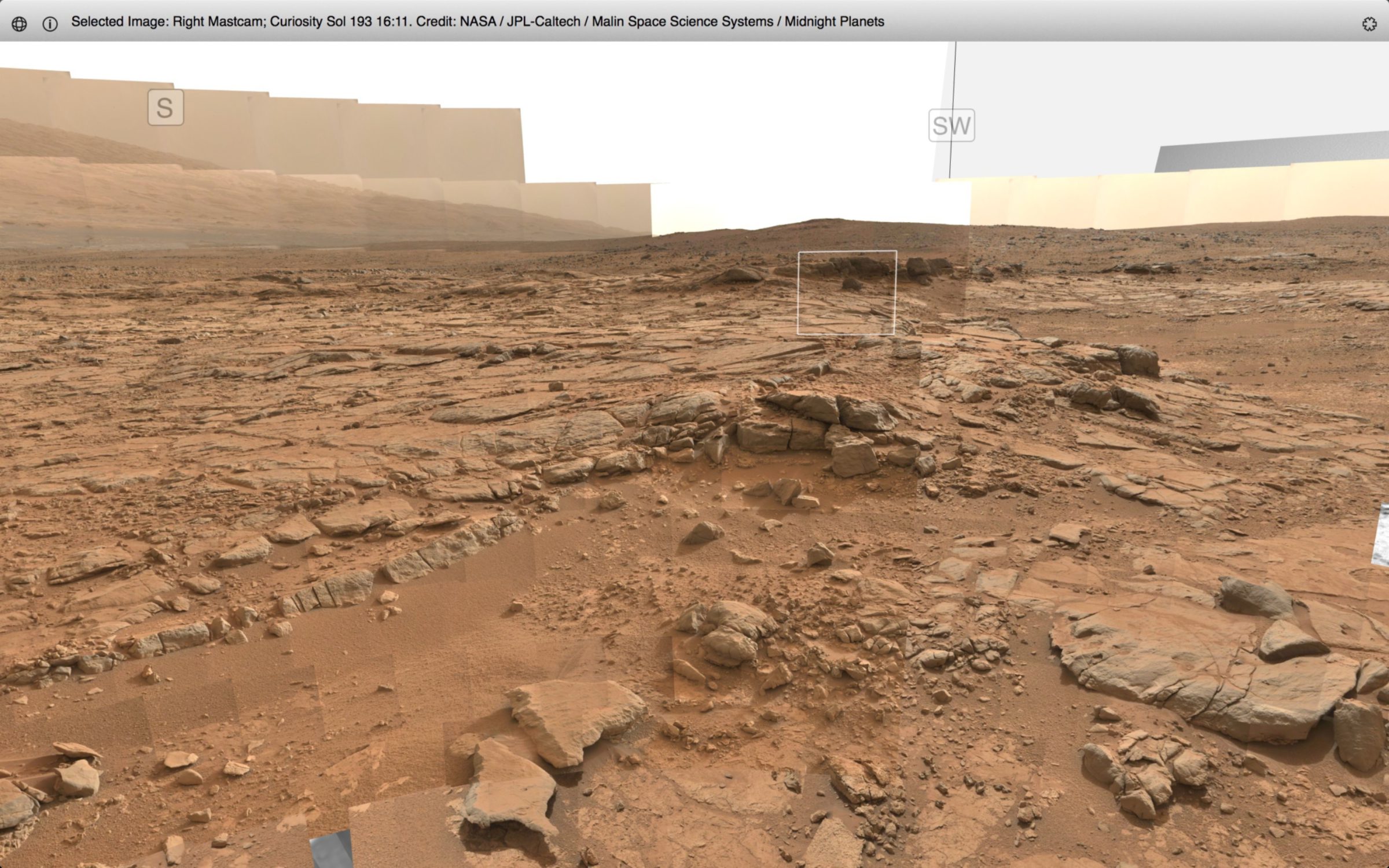

Here's a wider view, taken from near Curiosity's current position, to provide context. Point Lake (white square) is sitting on top of the Gillespie unit (in the middle ground) which itself overlies the Sheepbed unit (which is what Curiosity is sitting on as she shoots the photo).

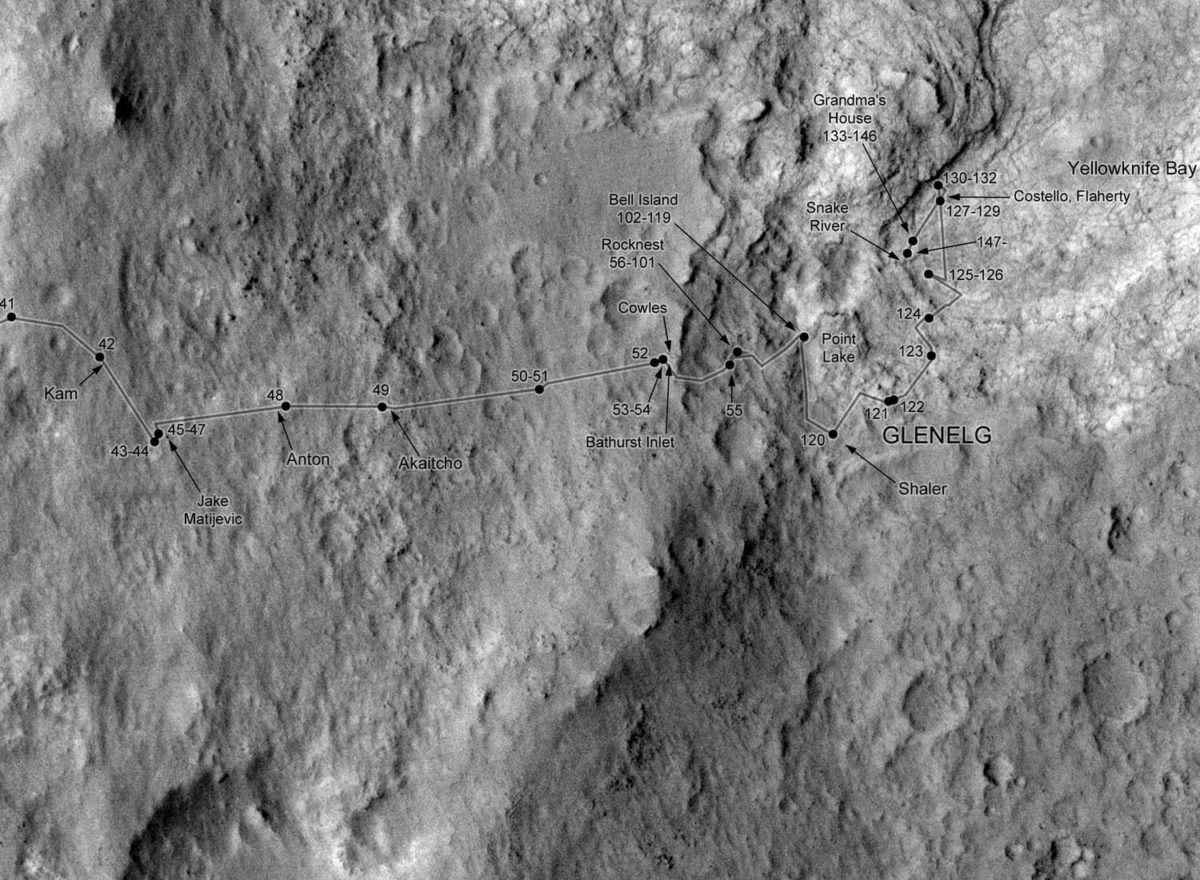

The Shaler outcrop should be almost directly behind the Point Lake outcrop as seen in this photo, but I guess it's blocked by Point Lake because I don't see it. Here's a route map that shows the relative positions of these various locations. Shaler was seen on sol 120, before the rover skirted around the Point Lake ledge on sols 121 to 124 to descend into Yellowknife Bay.

And as a reminder, here's what that beautiful Shaler outcrop looks like, in a panoramic view from the top of Point Lake on sol 110:

Joy said, "The trip to Glenelg has been well worth it. The science team is very pleased with the results that we've gotten. Once we are done with these three activities, we're going to hit the road and embark on a new phase of the mission." The science team has spent so long in the Glenelg region that pretty much everyone is "antsy" about beginning the drive to Mount Sharp. They "want a change of pace." There are no particularly obvious sites along the traverse for science stops, as seen from orbit anyway. But there will be stops, typically at outcrops of bedrock. They may even zoom past something and then decide to backtrack to check it out.

Here is an early crack at a traverse map for Curiosity, made by Ryan Anderson a long time before the landing. The actual traverse is going to differ in many details, the number one reason being that Curiosity isn't starting from the position that Ryan assumed, but it provides sort of a guide to what we might expect. I added the yellow dot to show you where Glenelg is. (Note that there is a very helpful "finger" of black sand dunes that points right to Glenelg; that's how I always orient myself to orbital views of Curiosity's landing site.)

This is one slide from a much longer presentation (PDF) that goes into considerable detail about interesting potential science stops along the way from Curiosity's presumed landing site to the rocks exposed among the sand dunes that lie at the base of Mount Sharp (which are at the bottom of this map). The funny thing about that presentation is that Ryan identified nothing of particular interest between the "high-thermal-inertia unit" (which is what Curiosity has just drilled) and those dune fields. Joy said that the science team is motivated to get moving to Mount Sharp -- I expect that while there will be stops, they are going to be booking along through terrain that is remarkable only for the fact that the views are awesome and they are being shot by a rover on another planet. Appreciating those views is something Curiosity can very easily do in a few minutes in the morning or afternoon before or after drives. Let's get rolling!

As I was posting this update, Dawn Sumner (a member of the Curiosity science team) Tweeted me this:

@elakdawalla When I feel like slowing down w/ @marscuriosity , all I have to do is look at this: twitter.com/sumnerd/status…

— Dawn Sumner (@sumnerd) June 5, 2013

Right on!!

Note: an earlier version of this post incorrectly identified Jim Erickson's title. He is now Project Manager, not deputy Project Manager.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth