Emily Lakdawalla • Mar 12, 2013

Yes, it was once a Martian lake: Curiosity has been sent to the right place

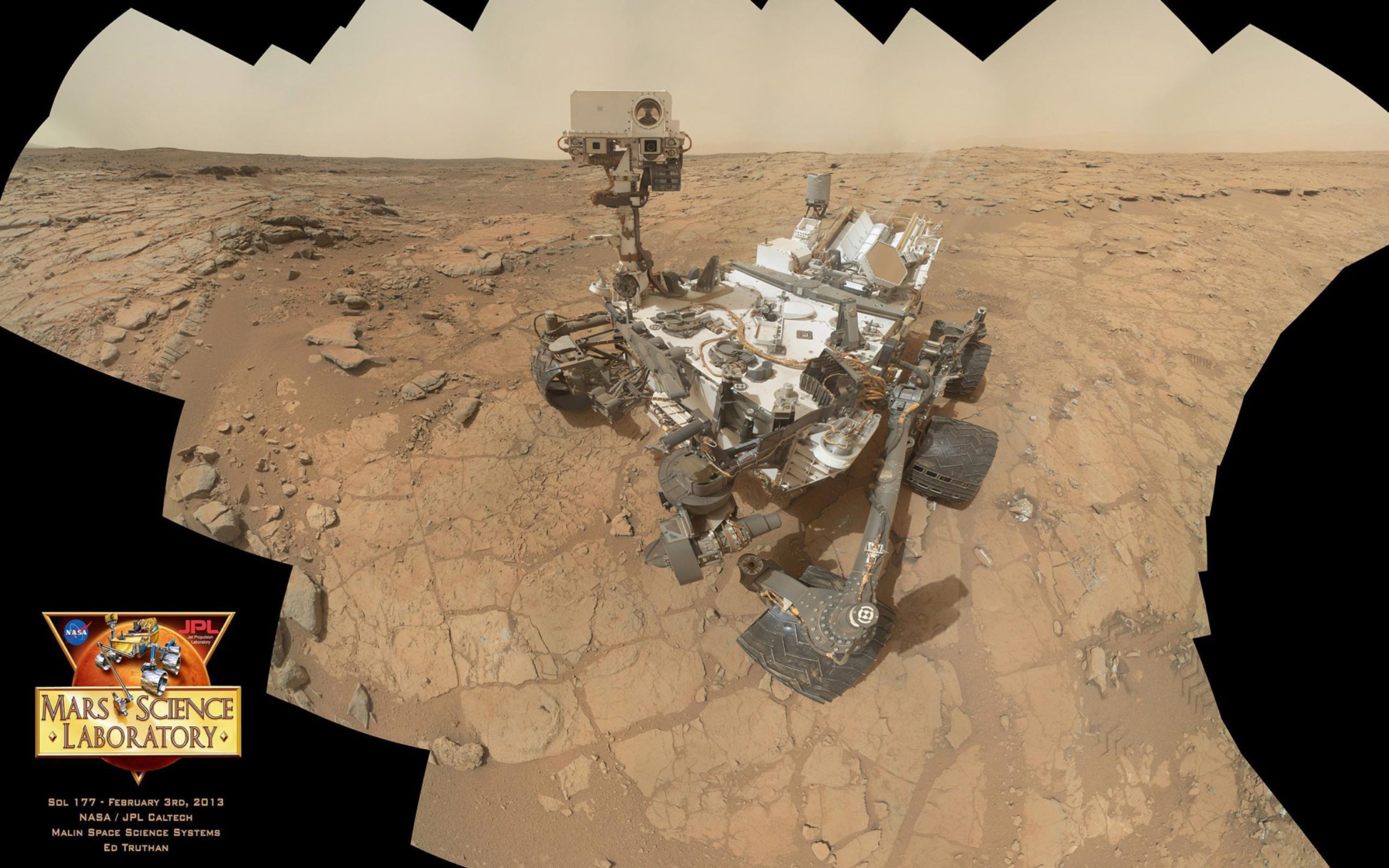

The news from the Curiosity mission today is this: Curiosity has found, at the site called John Klein, a rock that contains evidence for a past environment that would have been suitable for Earth-like microorganisms. The rock contains fairly abundant clay minerals, which are usually formed by the alteration of other minerals in the presence of water. Unlike the hypersaline or strongly acid only rarely watery environments explored by Spirit and Opportunity, the environment chronicled by the rocks at John Klein looks a lot more pleasant, with neutral or slightly alkaline pH, maybe slightly salty.

Taken together, the mineralogical and geomorphological observations suggest that the rover's wheels are sitting on an ancient Martian lakebed, an environment that has been hypothesized to have existed on Mars but which has never before been explored in situ.

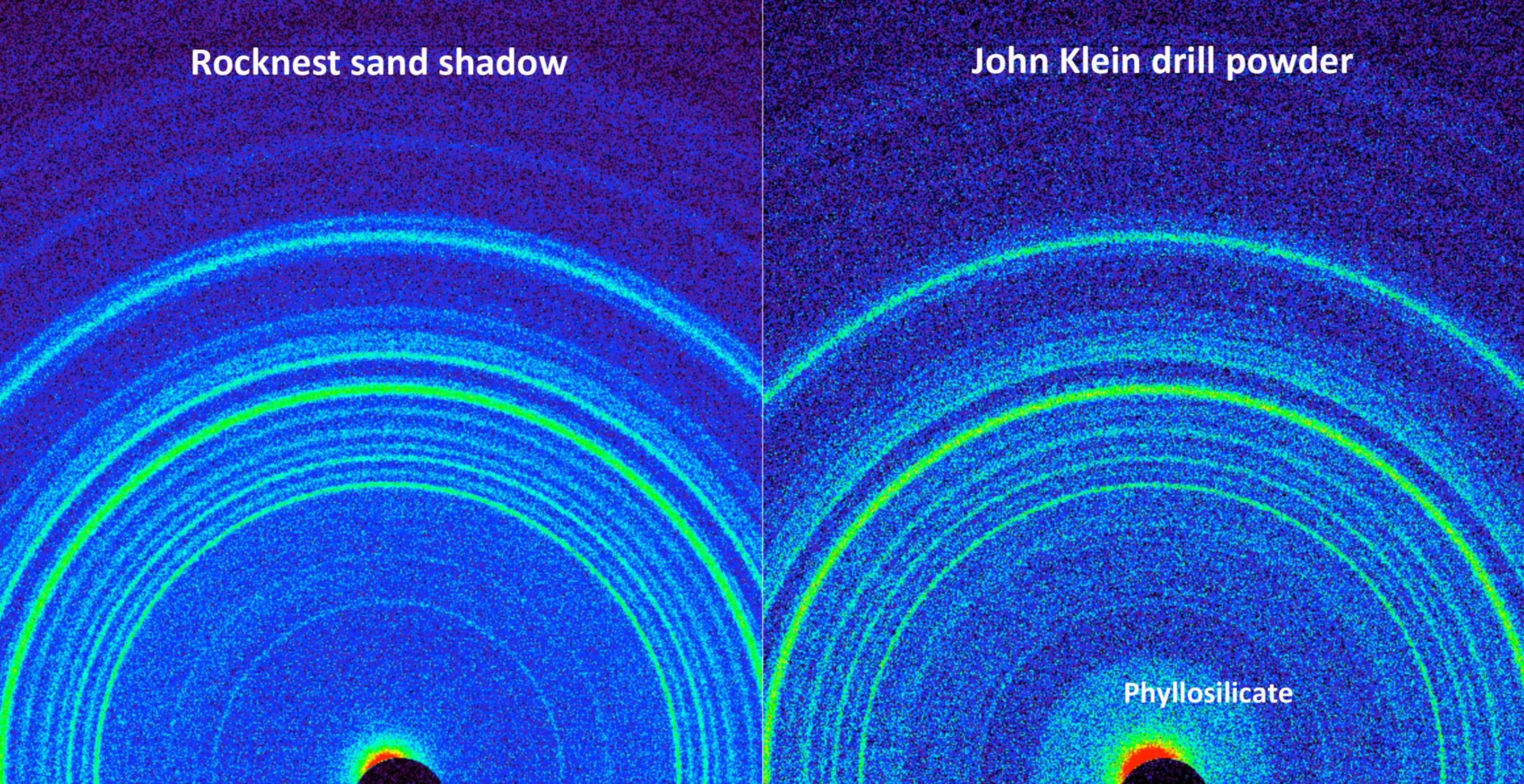

The rock also contains both oxidized and reduced forms of the same elements, meaning (said John Grotzinger at today's press briefing) that there are chemical gradients that Earth-like life could potentially exploit as an energy source. I won't go into detail on the chemistry of the findings because I am hoping that I will get a lot more detail, more thoroughly explained, with more discussion of the relative certainty of the findings, at next week's Lunar and Planetary Science Conference. But here are the pretty rainbow Chemin X-ray diffraction spectra they released today.

This isn't "mission success" for Curiosity yet, but it's an important step in the right direction. The overarching scientific goal of the Curiosity mission is "to explore and quantitatively assess a local region on Mars' surface as a potential habitat for life, past or present." Note that the way this is written, Curiosity could be declared a successful mission whether or not they ever found such a habitable environment; it's the exploration and assessment that's important. At John Klein that exploration has begun, but there's much more to do.

Although today's briefing featured the Curiosity mission, this announcement has ramifications far beyond Curiosity, and here's why. It wasn't Curiosity data that led the rover team to a decision to explore at John Klein. The decision to drive to this particular spot was made based upon the enormous data sets acquired by all of Curiosity's predecessors. The real significance of this moment is that it ground-truths some of the conclusions drawn from orbital data sets.

Two orbiting missions in particular deserve credit for the discovery of this ancient habitable environment: ESA's Mars Express and NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. Both of them carry imaging spectrometers (OMEGA on Mars Express, CRISM on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter) that are capable of mapping variations in surface composition with high resolution, unlike their coarser-resolution predecessors TES on Mars Global Surveyor and THEMIS on Mars Odyssey.

But resolution wasn't the only difference among these spectrometers. OMEGA and CRISM see a different part of the electromagnetic spectrum than TES did and THEMIS still does. TES and THEMIS operate in the thermal infrared, where variations in the composition of silicate minerals express themselves as wiggles in spectra. OMEGA and CRISM operate in shorter, near-infrared wavelengths, which gives them the ability to detect water bound into crystals, and to find other minerals like sulfates and carbonates. Clay minerals mapped out in tiny exposures by OMEGA and CRISM became the important target for the future Mars Science Laboratory mission, and Gale crater was selected in part because of the conclusion that clay minerals were present there.

There is one fly in the ointment. Neither of the two orbiters saw a strong signal from clay minerals at the specific spot where Curiosity is sitting. Look at that map and you'll see there's no strong spectral signal of any kind from the John Klein unit. It's got a scattering of green and blue pixels, which would imply the presence of clays and sulfates, which is consistent with today's results; but the signal is not strong. Not in near-infrared wavelengths, anyway. But this unit was a bright beacon in Mars Odyssey THEMIS maps of Gale. I'm looking forward to hearing the Curiosity team reconcile all these data sets. And I'm looking forward to going to the mountain to see why the clay- and sulfate-mineral signatures are so much stronger there.

Going back to Curiosity's overarching goal, the rover has now succeeded in exploring and quantitatively assessing a local region on Mars' surface as a potential habitat for life. Obviously, though, there's a lot of work yet to be done. Curiosity's next steps will include further study of the John Klein site with at least one more drilled sample in order to understand the compositional variety of the site, and to understand what kind of time might be represented by this rock -- how long did this environment last? Was it intermittent, recurrent, or continuously present for some lengthy period of time?

Curiosity's team members would also like to understand how the lakebed sediments found at John Klein relate to the huge stack of sediments that form Gale crater's central mound. John Klein could potentially have formed in just about any period of Mars' sedimentary history. The John Klein rocks could have formed at the toe of an alluvial fan that comes down from Gale's rim, which would imply that the rock is young relative to most of Mars' geologic activity. That's how it's been mapped in Ryan Anderson and Jim Bell's Gale crater survey. Or they could actually represent the very lowest levels of the sedimentary stack that includes Gale's central mountain, in which case they would be quite old. It's not inconceivable that they represent some intermediate age, some intermittent pool of water that formed for a time on the floor of the crater after the central mound formed but before the alluvial fan formed. Figuring out the stratigraphic relationship between John Klein and the mountain is going to be a major motivation of the next several months of Curiosity's mission.

I saw this joke earlier today on Twitter, but it actually kind of sums up the significance of today's findings: Curiosity has been sent to the right place. It has an instrument suite that was particularly designed to study the kinds of rocks it has found. Hooray for the Mars program! Hooray for the "squiggly lines" of infrared spectra!

@elakdawalla @sarcasticrover "NASA Rover Finds Conditions Suitable For NASA Rover"

— Walt Stone (@Cuppacafe) March 12, 2013

Back on Mars, the rover is still not doing science operations; they are continuing to work on understanding and fixing the problem with the Side A computer. While I am sure that none of the Curiosity team would have wished for this forced break in science operations, I hope it'll have a good effect in that the couple of weeks of no new data right before the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference might mean that the science team has had a chance to actually think about their data before they speak about it.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth