Emily Lakdawalla • Dec 13, 2012

How GRAIL will meet its end

The twin GRAIL spacecraft are nearly out of fuel, and are being directed to a controlled impact near the north pole on the near side of the Moon on December 17. Ending the mission in this way has been planned all along; the news here is the time and location of the planned impact. Here's a preliminary map of the location, an unnamed mountain located at 75.62°N, 26.63°W. (The linked map says "east" but the inset map shows that the numbers are negative and a larger-scale map shows it west of center, so I'm pretty sure it's west, not east.) The end will come on December 17 at 22:28 or 22:29 UTC. Ebb will hit first, followed by Flow about 30 seconds later. Here's a video:

Ian O'Neill Tweeted his own take on this video: "GRAIL impact trajectory, with added drama (NOTE: In space, no one can hear a probe scream):

Some quick facts about the impact:

- They will target the site in a maneuver tomorrow morning.

- It won't be observable from Earth; it's happening in the dark and there'll be no fuel left in the tanks.

- The location was controlled primarily by their desire to collect science data for as long as possible (more on that below).

- Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter will attempt observations of the impact with LAMP, as it did for the LCROSS mission.

- Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter will do followup imaging of the impact zone to look for the craters. Scientists hope to learn about the mechanical properties of the mountain (which is part of a degraded crater rim) from the pattern of the ejecta.

- If they were hitting the ground vertically, they'd be expected to make a 3- or 4-meter-diameter crater.

- But they are coming in at an angle of about 1.5 degrees above horizontal, so will be hitting the ~20-degree slope at a fairly low angle. That will reduce the size of the resulting crater. But it's better than impacting a level surface; Zuber said that the spacecraft would just leave "skid marks" if they did that.

- The low-angle approach would have made it impossible for them to consider an attempt to impact a permanently shadowed deep crater near a pole, as LCROSS did; GRAIL's circular-orbit trajectory means they have to impact a topographic high.

I've already explained what GRAIL accomplished in its primary mission. GRAIL has returned much more data since the primary mission ended, from extended missions operated at much lower orbits: first, 22 kilometers, and since December 6, an astonishing 11 kilometers.

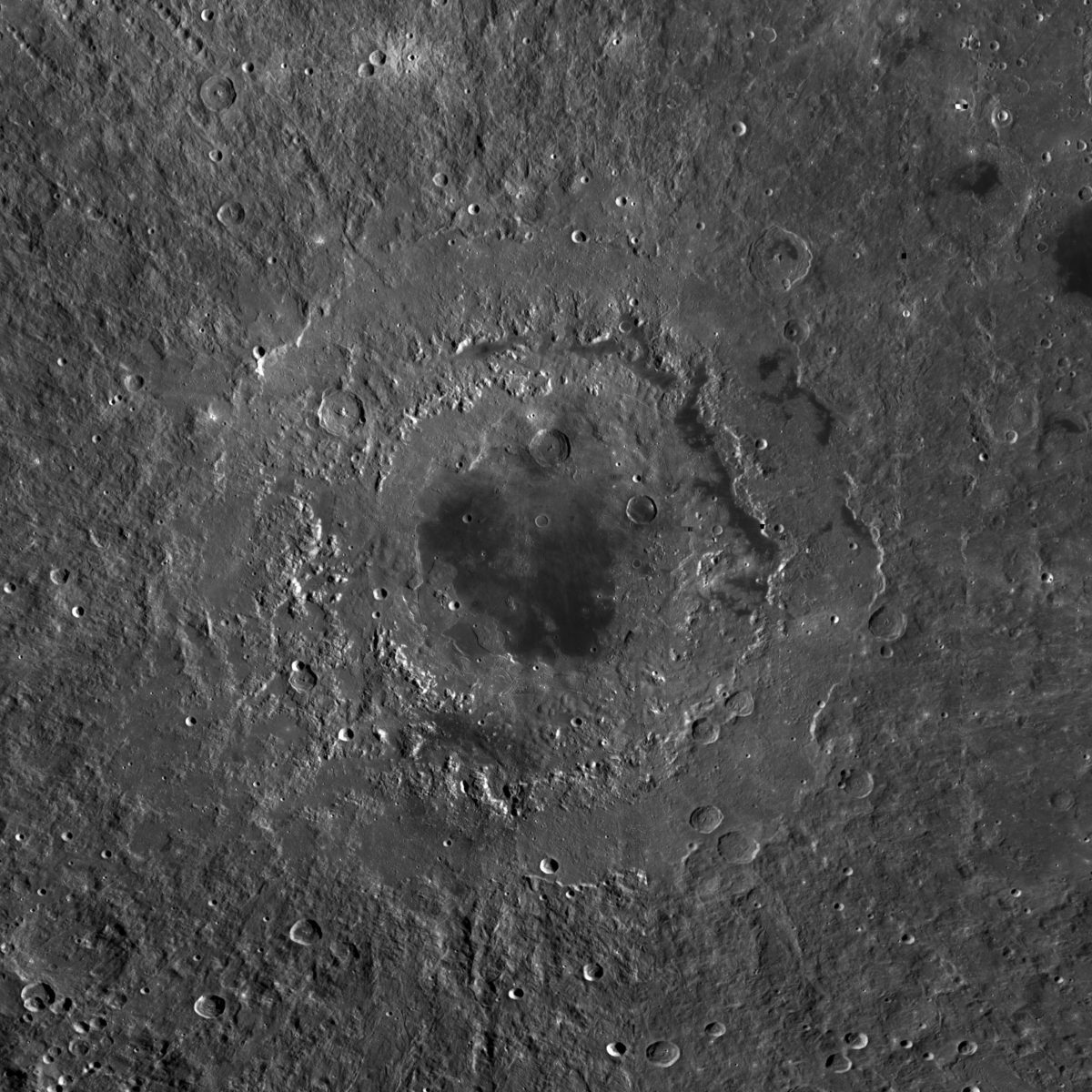

That last low-elevation phase involved orbits over the Orientale impact basin. Orientale is located on the left side of the Moon, just visible peeking over the edge from Earth. It's the youngest of the large impact basins, and the best-preserved, with beautiful concentric rings. Those rings are actually tall mountains; at times, Zuber said, GRAIL was skimming only 2 kilometers over the tops of those mountains.

GRAIL's data taken from such a low elevation will allow exquisitely detailed mapping of the underground structure of the basin. I can't wait to see that. But to maintain such a low altitude took three firings of the maneuvering rockets each week. The spacecraft are now running very low on fuel. They could have lasted a little bit longer if they hadn't flown to this low altitude, but they'd done what they could at higher altitude. Every time they halved the altitude, they quadrupled the precision of their data.

One of the coolest things they showed at today's press briefing was a video taken from GRAIL's tiny MoonKAMs showing Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter flying over the Moon. It's just a moving dot but still is inexpressibly cool.

Before the mission ends, they'll do a few things that don't have anything to do with their science mission but which have immense value for future mission planning. For example, GRAIL's programmers had developed lots of software designed to handle problems that never arose; they will test some of that software in flight. Also, they'll do a burn-to-depletion maneuver, something I explained at the end of the Stardust mission last year (see here and here). At the press briefing, project manager David Lehman said that it would take between 0 and 9 minutes to burn through the remaining fuel.

Deliberately killing a functioning spacecraft is sad, but in this situation (as with many other orbital missions) it is the responsible thing to do. It's better not to have derelict spacecraft orbiting as space junk that could cause future navigation problems. When an impact is inevitable and there is anything of historical or scientific interest that is threatened by the impact, it's responsible to target an area well away from such sensitive spots. Just as Galileo was deliberately crashed into Jupiter to avoid the possibility of an uncontrolled impact on Europa, they're making sure to dispose of GRAIL far away from the relics of previous human and robotic Moon landings.

The gravity maps that GRAIL produced will improve the precision of future lunar landings, making them less risky and less expensive. GRAIL itself did well with its budget; the mission will actually return 8 or 9 million dollars to NASA when all's said and done. Since when does that happen?

Given how well this mission has worked, I do wonder what it would cost to make copies and fly them elsewhere. The biggest hurdle for that as far as I can see is the fact that GRAIL didn't need a big radio transmitter because the spacecraft were so close to Earth. But it could still work from Mars. The data volume, about 640 MB through the prime mission, wouldn't be a problem if relayed through Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. Anybody wanna propose a mission?

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth