Emily Lakdawalla • Sep 23, 2011

Tethys and Dione don't seem to be active after all

About four years ago I wrote a blog entry about an ESA press release about paper published in Nature that suggested that Saturn's moons Tethys and Dione might have volcanic activity, like Enceladus. A new paper published in Icarus casts doubt on that conclusion. To be clear, it was the press release that called Tethys and Dione "Two more active moons around Saturn." The Nature paper didn't actually go that far.

Here's my summary of the Nature paper, "Tethys and Dione as sources of outward-flowing plasma in Saturn's magnetosphere":

The paper reports the detection of plasma -- charged atoms -- flowing outward in Saturn's spinning magnetosphere, a measurement made using Cassini's Plasma Spectrometer. As is true of most spectacular-sounding press releases, the story told in the actual research paper is more circumspect than the one told to the media. In this case, the paper does not actually mention the possibility of geologic activity of any kind on Tethys and Dione (much less does it mention volcanism). Instead, it states only that there are "distinct plasma tori associated with [Dione and Tethys]." Now, plasma tori ("tori" is the plural of "torus," which is a 3-dimensional figure that looks like a doughnut) are definitely associated with active bodies like Io and Enceladus, so to report that there appear to be plasma tori associated with Tethys and Dione is very interesting. But it's not conclusive evidence that those two moons are active, and the paper never actually states that they are.

The Icarus paper, " Search for and limits on plume activity on Mimas, Tethys, and Dione with the Cassini Visual Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (VIMS)" reports the results of six years of searching for Enceladus-like plumes from Tethys and Dione. VIMS doesn't have the resolution of Cassini's cameras, but they weren't exactly trying to spot visible plumes. Instead, they were checking to see if the moon would appear to brighten when you look at it from very high phase angles. "Phase angle" refers to the angle from the Sun, to the moon, to the observer. At low phases, moons look "full," and they are at their brightest. At high phase, we usually see a crescent that is much dimmer. Here's an example of this effect with Rhea:

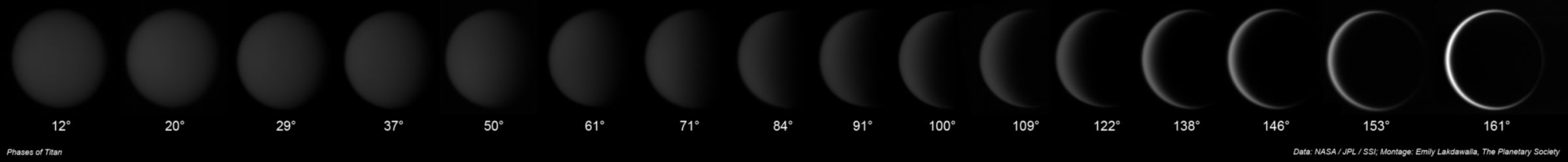

If the moon involved has an atmosphere, though, something funny happens. Going from low phase to high phase, you first see the moon appear to dim, as you expect. But when you get to really high phases, it suddenly starts brightening again. Here's the poster child for moons with atmospheres, Titan:

What's happening is that tiny particles in the atmosphere are "forward scattering" the light from the Sun. It's the same effect that makes Enceladus' plumes appear to be bright when lit from behind. According to the Icarus paper, when VIMS looks at Enceladus at a near-infrared wavelength of 2 microns, Enceladus is very nearly as bright at high phase angles (above 160 degrees) as it is at very low phase angles (less than 1 degree), a fact that they call "astounding."

Now, Cassini's camera team has been searching for plumes at Dione and Tethys using the same viewing geometry that they used to spot the ones at Enceladus, and they haven't found them. The VIMS team searched at that 2-micron wavelength to see if there was any hint of that telltale forward-scattering peak from Mimas, Tethys, or Dione, and they report in the Icarus paper that they did not see the peak. Based on the sensitivity of their instrument, they determined that Dione, for example, could be no more than 1% as active as Enceladus (where "active" is defined by "how much water vapor it spews into space").

Of course, this doesn't prove that there is no geologic activity on these three moons; maybe there are plumes, but they happened to be pointed in the wrong direction during the VIMS imaging. Or maybe they're only rarely active, and weren't active at all when VIMS was looking.

I always like to see negative results reported. The story here is that one group reported that something might be there, and another group followed up on that hypothesis and said, nope, it appears to be wrong, though we could be wrong about our conclusion that the previous paper was wrong. Science in action! At the forefront of science, what scientists publish usually turns out to be at least partially wrong, eventually. And statements of certainty are rare.

Of course, it doesn't enter the public record that way. The "Dione might be active" paper got the full press-release treatment when it was published, with misleading headlines like "Cassini finds Saturn moons are active," while the "Dione is probably not active" paper did not. As a result, a preponderance of information on the Web will tell you that Dione may be -- or even is -- geologically active.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth