Emily Lakdawalla • Jan 09, 2009

The wind blows rocks on Mars?

There's a press release that's making the rounds today that neatly explains the regular spacing of rocks on the plains on Mars. Everywhere we've landed spacecraft on Mars, they arrive on relatively flat surfaces that are covered with rocks. This in itself is odd. On Earth, you mostly see rocks where there are steep slopes. Where things are flat, you mostly don't see rocks (with the notable exception of places where there have been glaciers). It has to do with how much energy it takes to transport rocks. When you have steep slopes, gravity does most of the work in transporting rocks around; flowing water helps things along. Once the slope levels out, though, gravity doesn't work to move rocks anymore, so it's rare to see large rocks in a flat area.

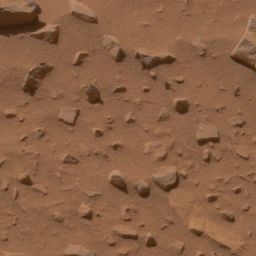

On Mars there are rocks everywhere. The difference is that Mars' landscape is shaped in large part by impact processes. Far-away impacts can toss rocks for miles, and they fall where they land. So it's not particularly surprising that you see rocks everywhere, even in flat places on Mars. What is a bit surprising is their even spacing. Here's an example of a rock-strewn landscape selected more or less at random from the early part of Spirit's mission, when it was dashing across the flat plains to the east of its landing site toward the Columbia Hills.

NASA / JPL / Cornell / calibrated color by Daniel Crotty

Scattered stones on the Gusev plains

During its dash across the plains to the Columbia Hills, Spirit surveyed the rocks and soils along the way. This image was taken on sol 149, fairly close to the Hills. Stones are scattered evenly across the surface.Apparently it's been suggested that wind actually pushed the rocks around, though I find that notion just a little hard to believe. Remember the air is a hundred times thinner on Mars than it is on Earth. Anyway, we don't need that explanation, because Jon Pelletier and coworkers have suggested a more elegant explanation.

It does involve the wind, but the wind doesn't move the rocks, at least not directly. What the wind does do is lift sand; sand particles jump (or "saltate") along the ground, knocking into each other and launching more sand particles. When the wind runs into a rock, it loops and whirls, scouring the area right in front of the rock. Over time, it digs a pit in front of the rock. At the same time, the sand that was scoured from in front of the rock gets deposited in the wind shadow behind the rock. Do this for long enough, dig a steep-sided enough pit, and one random day the rock will tip forward, rolling in the upwind direction, into the pit. Rinse and repeat, and you get rocks trooping across the landscape over time. (The press release didn't give a time scale for this process.)

That explains how rocks can move, but how does it explain an even spacing? Well, according to the release, when you have a cluster of rocks, "those in the front of the group shield those in the middle or on the edges from the wind, Pelletier said. Because the middle and outer rocks are not directly hit by the wind, the wind creates pits to the sides of those rocks. Therefore, they roll to the side, not directly into the wind, and the cluster begins to spread out."

Neat. It can't be a fast process. But just think: it's still windy on Mars today, so it's probably a process that is going on today. And think about how much windy plains there is covering Mars, and how many millions (billions? more?) small rocks there are on those plains. Let's say that for any given rock, there's only a one-in-a-billion chance that it will tip over in any given second. If there's a billion rocks on Martian plains, that'd be one rock tipping over every second, all over Mars. Mars may look dead, but it's in constant motion!

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth