Casey Dreier • Aug 31, 2017

A future comes into focus for the Mars Exploration Program

Before I discuss Monday's announcement that NASA intends to pursue sample return from Mars, I hope you'll indulge me in sharing a (brief!) personal story that has been present in my mind this week.

It's about how my life changed before the Atlas V carrying NASA's Curiosity rover even reached space.

It was my first rocket launch. It was my first mission with a direct connection to the science team and their raw hopes and fears for the launch. And it was a mission to Mars, for chrissakes, and vivid memories of watching the landings of Pathfinder and the MER rovers, pouring over the engineering drawings and pictures of Viking as a kid, all joined into the powerful melange of emotions I felt as I watched that rocket disappear into the blue expanse, never to return.

At the time, MSL Curiosity was the last Mars surface mission on NASA's books. A year before, the space agency had abruptly pulled out of the proposed joint ExoMars mission with ESA. All that remained was the MAVEN orbiter launching in 2013, and, après MAVEN, rien.

That thought haunted me that evening as we celebrated the successful launch. I found myself asking the question, "why am I not doing everything I can to help fix this?" and I found I had no good answer. Within a year I had changed careers and joined The Planetary Society to help run its advocacy program.

That decision consciously happened the evening of the launch, but unconsciously it happened during the launch itself, perhaps when the Atlas V punched through a cloud and emerged out the other side. I was hooked.

Thankfully, more Mars missions came relatively soon after the success of Curiosity's landing on August 6, 2012. Later that month, InSight was selected as a small-class mission through NASA's Discovery line. The Mars 2020 rover project (so named for the year it will launch) was announced in December 2012.

The National Academies released its Decadal Survey for Planetary Science the year before, titled Visions and Voyages, and its top program recommendation for flagship missions was a mission to Mars to begin a campaign for sample return. It took determined effort from the scientific community and advocates within NASA to ensure Mars 2020 adhered to those recommendations. Even now, the official mission description for Mars 2020 hedges on any guarantee of sample return, stating only that "a future mission could potentially return these samples to Earth."

So why would NASA invest hundreds of millions of dollars—a large portion of the project's price tag—on an advanced sampling system for Mars 2020 but not follow through with sample return? There are many ways to interpret this, but fundamentally it comes down to cost, as it so often does. As classically envisioned, a sample return campaign would require three flagship-class missions. The first finds and collects the samples. That mission is Mars 2020 and it will cost around $2.4 billion. But Mars 2020 contains a full science suite, it's not just a sample acquisition device. So great science could be achieved even without returning the samples.

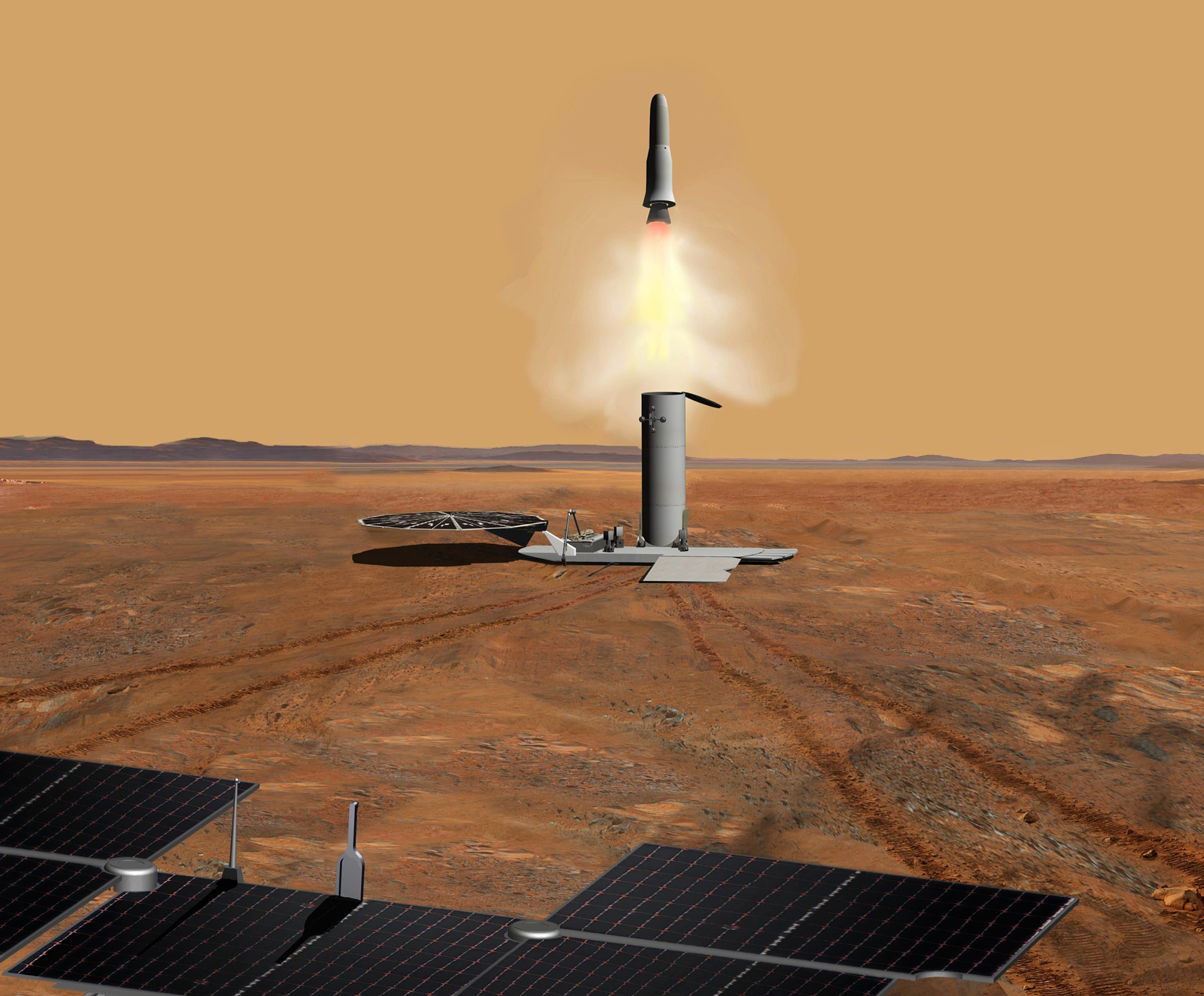

The cost problems were exemplified at a presentation earlier this year to the Space Studies Board of the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine; Mars Exploration Program Director Jim Watzin discussed early studies of two follow-on missions to first fetch the samples and launch them into Mars orbit, and then rendezvous with them and return them to Earth. Early estimates placed these missions at $4 billion and $2 billion, respectively. The cost of these missions would place an onerous financial burden on the entire Planetary Science Division in the 2020s as it also pursued a flagship mission to Europa (and potentially a lander as well), on top of PSD's commitment to smaller missions to other destinations in the solar system. Even with the division's improved funding outlook, there would not be enough resources to simultaneously pursue all of these endeavors. This has always been the problem with Mars sample return.

In the meantime, no new missions to Mars had been announced since 2012. The report released by The Planetary Society earlier this year, Mars in Retrograde: A Pathway to Restoring NASA's Mars Exploration Program, highlighted the creeping problems associated with a lack of new mission starts, including an aging telecommunications infrastructure and an absence of program clarity entering the 2020s. The entire Mars program had been reduced to a single mission, Mars 2020, implying a future for sample return. But said future was just that—implied and with no commitment.

As of Monday, that future is beginning to come into focus. While there was no official mission start or timeline presented publicly, the fact that NASA's top science administrator spoke about the intent to pursue the return of samples from Mars was a big deal. It is the first time sample return has reached this level of official public discussion, and marks a critical step toward clarifying the future of the Mars Exploration Program. By focusing on the fetch rover and Mars Ascent Vehicle and potentially partnering with another entity on a rendezvous and return orbiter, NASA could save billions on the overall mission.

So first and foremost: this is very good news for Mars fans, Mars scientists, and, I should note, supporters of the Decadal Survey process. NASA took the recommendations from the community seriously, and it looks ready to prioritize this top goal of the Mars science community for the first time ever. The Planetary Society is very supportive of this first step. I believe this is the best news Mars has had since 2012.

Second: by going straight to sample return, NASA must move relatively quickly in order to rely on its existing communications relay assets already at Mars. As we discussed in our Mars in Retrograde paper, the two primary communications relay satellites, Odyssey and the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), will be 20 and 16 years old by the time the Mars 2020 rover lands. And while Odyssey is not expected to last far beyond 2020, NASA now believes MRO may be able to make it to 2026. The MAVEN spacecraft could alter its science orbit to provide better communications coverage, though potentially at a cost to its extended science mission. ESA's Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO) arrived at Mars last year and carries a NASA-provided communications package for telecom relay as well.

Should NASA indeed launch a Sample Return Lander (SRL) mission with a fetch rover and Mars Ascent Vehicle in 2026, the youngest orbiter capable of relaying data from the surface, TGO, would be 10 years old while the most capable telecommunications asset, MRO, would be 21 years old. Pushing the SRL mission further into the future adds additional risk to these assets and to the mission. Thus, the onus is on a speedy commitment to sample return to ensure mission success. This is obviously a good thing from a timing perspective for the top science goal of the Mars community, but it does not address longer-term infrastructure issues at Mars. Which brings me to…

Third: the upcoming decadal survey process for the years 2023 - 2032 will be critical for the Mars orbital science community, and Mars science itself. The next report is already on the horizon. If this plan by NASA does go forward, the next decadal survey could be the first time that the planetary science community debates the priority of Mars science after achieving its biggest goal in the program's history.

There is a lot of important science left to do at Mars, and the Red Planet will by no means be fully explored even after sample return. Scientists dependent on data from spacecraft orbiting Mars, in particular, will have to engage the community and make their case for new flight projects, seeing as how they are facing a drought of new missions (though NASA's competed Discovery program remains an option for mission proposals). Given the potential of international partnerships for the orbital component of the return mission, there may be opportunities to support NASA science teams on non-NASA missions as well; much more detail is needed. But again, the decadal survey is the process by which the U.S. planetary science community argues with itself to reach a relative consensus on its priorities. It will be fascinating to see where Mars science fits into this future debate.

I should emphasize that these are, fundamentally, great problems to have. The Mars program has clarity for the first time in years, and sample return is being prioritized at NASA, just as the community recommended. I think the decision to pursue sample return first is the right one given the budgetary and timeline constraints. Given the deep uncertainty and struggle of the Mars program over the past few decades—a program that has faced an ever-receding goal of sample return since the 1990s, this marks a bold step forward.

The Planetary Society intends to follow this issue exceptionally closely, and to get our members and supporters engaged in this endeavor. Exciting times are ahead. After all, who knows what we will find?

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth